By the very intrinsic nature of the Greek lands and topography, large-scale cavalry forces were never an option for most burgeoning city-states of Greece. This was especially due to the rough nature of the terrain that was not exactly conducive to the trotting of unshod horses.

In essence, their relative geographical position made Greeks the ‘men of the spear’ – a military tactic that preferred tight formations over extensive battlefield maneuvering. This ‘tradition’ of hoplites in Greek warfare ultimately made way for the famed Macedonian phalanx and their Greek successor states – thus dominating the battlefield for the next century after Alexander the Great’s death.

Contents

- A Force NOT Inspired by Either Spartans or Athenians

- The Macedonian Phalanx Was Originally Composed of Semi-Nomadic Herders

- A Standard Phalanx Comprised Light-Armored Infantrymen

- The Incredible Battlefield Tactics of the Macedonian Army

- The Phalanx Was More Trained Than Comparable Greek Hoplites

- Members of Alexander’s Army Were Subject to Harsher Discipline

- Conclusion – The Psyche and Decline of the Macedonian Phalanx

A Force NOT Inspired by Either Spartans or Athenians

The Spartans were dealt a stinging defeat at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BC, by not their long-term rival Athenians, but rather by the ‘upstart’ city-state of Thebes. This ensured a brief period of Theban military supremacy in the 360s, with its influence and primacy reaching the northern Greek states of Thessaly and Macedon.

Suffice it to say, an impressionable man named Philippos (or Philip II, who was the youngest son of Macedonian king Amyntas III) took note of the great Theban general Epaminondas and his fascinating tactics. One such incredible innovation involved the so-called Sacred Band, an elite military force that was often specified as having 150 pairs of homosexual ‘lovers’.

Now while explicit evidence of Macedonian pederasty in their military is still not found, there are literary anecdotes on how such relationships played their larger role in political affairs in Philip’s time.

However, beyond sexuality, it was the scope of advanced battlefield tactics of the Thebans that was seriously inspirational to Philip II and his Macedonian phalanx. And, as the saying goes – “necessity is the mother of all inventions”.

By the time Philip assumed the reign of the nascent Macedon, the state’s army was all but vanquished – with their earlier king and many of the hetairoi (king’s companions) meeting their gruesome deaths in a battle against the invading Illyrians.

In essence, Philip had to tread carefully and take advantage of both delicate diplomacy and military innovation in order to keep his state and kingship intact. As Diodorus of Sicily explained –

The Macedonians because of the disaster sustained in the battle and the magnitude of the dangers pressing upon them were in the greatest perplexity. Yet even so, with such fears and dangers threatening them, Philip was not panic-stricken by the magnitude of the expected perils, but, bringing together the Macedonians in a series of assemblies and exhorting them with eloquent speeches to be men, he built up their morale, and, having improved the organization of his forces and equipped the men suitably with weapons of war, he held constant maneuvers of the men under arms and competitive drills.

Indeed he devised the compact order and the equipment of the phalanx, imitating the close order fighting with overlapping shields of the warriors at Troy, and was the first to organize the Macedonian phalanx.

The Macedonian Phalanx Was Originally Composed of Semi-Nomadic Herders

The Macedonians had one significant advantage over other southern Greek city-states, and that ironically related to “simple living”. In other words, the Greek hoplite was essentially a farmer who was tied to his land and made up the bulk of the middle class of his society’s economy. This resulted in more constrained campaigning seasons since the hoplites couldn’t be too far away from their agricultural lands.

However, in the developing state of Macedon, most of its male population took part in simpler economic activities, like herding animals (based on seasons). So, during times of war, when such conscripted men campaigned far and wide, their economic tasks could also be alternatively handled by older men, women, and even (in certain cases) children.

Essentially, manpower was never a significant problem for the Macedonian kings, with the kingdom’s burgeoning population spread across numerous villages, as opposed to being concentrated in urban centers or poleis. These simple yet hardy folk were given the incentive for better economic benefits (read ‘plunder’) that could have supplemented their meager incomes.

And thus the factor that limited other Greek city-states, allowed Macedon to field a ‘professional’ phalanx army that was properly motivated and prepared. As Alexander the Great made it clear to his troops, during the mutiny at Opis (as mentioned in Arrian’s Anabasis) –

Macedonians, my speech will not be aimed at stopping your urge to return home; as far as I am concerned you may go where you like. But I want you to realize on departing what I have done for you, and what you have done for me. Let me begin, as is right, with my father Philip. He found you wandering about without resources, many of you clothed in sheepskins and pasturing small flocks in the mountains, defending them with difficulty against the Illyrians, Triballians and neighboring Thracians.

He gave you cloaks to wear instead of sheepskins, brought you down from the mountains to the plains, and made you a match in war for the neighboring barbarians, owing your safety to your own bravery and no longer to reliance on your mountain strongholds. He made you city dwellers and civilized you with good laws and customs. Those barbarians who used to harrass you and plunder your property, he made you their leaders instead of their slaves and subjects.

A Standard Phalanx Comprised Light-Armored Infantrymen

To understand the evolution of the phalanx, one must first picture the equipment and role of the earlier Greek hoplite. Traditionally, comprising heavy infantry formations (Greek phalanx), the typical hoplite was mainly equipped with armor (which grew lighter over the centuries), a helmet, a thrusting spear (dory – ranging up to 8 feet long), a large shield (aspis), and a side sword (xiphos).

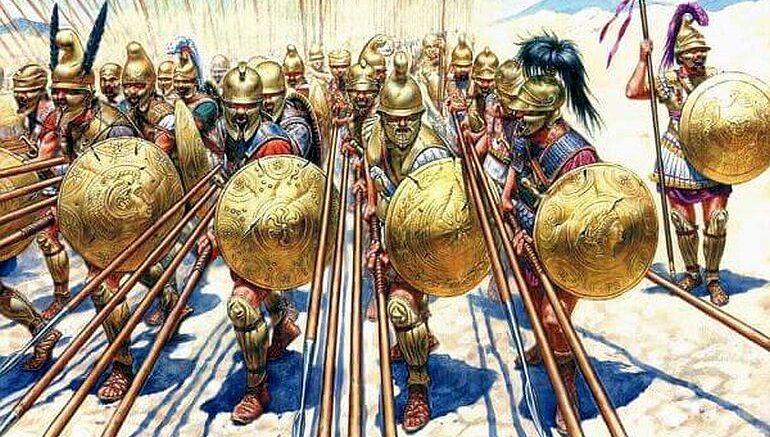

Now according to Polyaenus’ account of Macedonian military training, the foot soldiers (also called foot companions or pezhetairoi) of the newer Macedonian phalanx formation were equipped with a helmet (kranos), a light shield (pelte) – slung across the arm, greaves (knemides), and a longer spear (sarissa) reaching up to 18 feet (during Alexander’s time).

And while Polyaenus might have mistakenly omitted the sword, most historians are of the consensus that the Macedonian foot companion also carried the machaira (a shorter curved blade) or kopis (which might have been longer).

Interestingly enough, the smaller shield (pelte) – possibly adopted by various Greek armies under the reforms of Athenian general Iphicrates, was designed so that it could be slung across the left arm. This allowed the Macedonian soldiers to keep their left hand free. Consequently, they were able to wield (and guide) their very long spears with both their hands.

Now on closer inspection, we can see that the armor is conspicuously missing from this list of items. Going forward to a period 100 years after the death of Alexander the Great, there are accounts of Greek successor states’ phalanx functioning without any sort of heavy armor.

From such literary sources, one can surely put forth this conjecture – the Greek and Macedonian armies completely abandoned their unwieldy bronze cuirass. Instead, most of their military forces adopted the much lighter linothorax, an evolved armor system made from glued layers of linen.

Interestingly, one of the accounts of Polyaenus (in Stratagemata) records how Alexander spitefully armed his men who had previously fled the battlefield with the so-called hemithorakion – a half armor system that only covered the front part of the body. This punitive experiment made sure that the soldiers wouldn’t turn their backs on the enemy.

Lastly, in terms of practicality, heavy metallic breastplates would have been unnecessary for the well-drilled soldiers in the rear ranks of a guarded phalanx. This must have been a tactical (and practical) advantage welcomed by the kings who were usually short on funds and military equipment. This in turn led to a non-uniform nature of a phalanx – which is surely a far cry from the incorrect ‘heavy’ depictions of ancient Greeks and Macedonians in popular media.

The Incredible Battlefield Tactics of the Macedonian Army

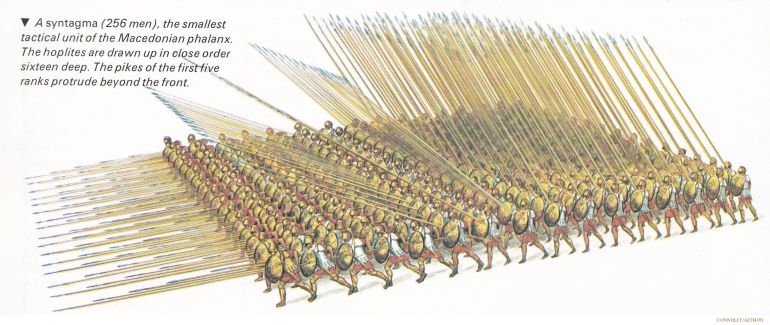

In terms of battlefield groups, the core unit of a phalanx was known as the syntagma – a square formation comprising ranks of 16 men deep. Interestingly enough, the formation allowed for 5 front ranks of men to keep their spears at a horizontal angle, while the last 11 ranks possibly kept their spears vertically positioned (as shown in the image above).

On the battlefield, it is presumed that the syntagma advanced with such orchestrated spear positions, thus presenting a bristling front of spear points to the enemy line. And while the tactics required very tight maneuvering on the part of the Macedonian foot companions, these core formations, in the center, were flanked by supporting light infantry (including peltasts and archers) and heavy cavalry (including the famed Hetairoi or Companion cavalry).

Some of the tactical spaces between the Macedonian phalanx formations were also filled by veteran soldiers known as the Hypaspistai (‘Shield Bearers’). They were tasked with the flexible battlefield role that bridged the gap between the mobile cavalry and the ‘anchored’ phalanx. The heavy cavalry, usually placed at the far right, was poised to charge at the weak points of the opposing force.

Considering these minute tactical details, it can be surmised that the Macedonian army was not overtly reliant on a particular group or formation of soldiers (unlike the hoplites of earlier centuries or even the knights of early medieval Europe). Furthermore, one could also theorize how such intensely disciplined and well-trained foot soldiers, aptly supported by cavalry, were more than a match for the front lines of “traditional” lightly armed Persian infantry.

Lastly, as the lines of foes met, the front row of the Macedonian phalanx presented its bristling spear points jutting out from a tight formation – thus almost creating an unpenetrable “spiky” front to the enemy infantry. The lighter shield rather helped the foot companion to deftly maneuver his very long spear from this tight body of troops.

To that end, in the ideal scenario, the Macedonian phalanx held the enemy formations in stagnant positions. This offered better battlefield control to the mobile forces of Alexander’s army, especially the hard-hitting Companion cavalry and Thessalian cavalry regiments. These forces could flank and even charge (or disrupt) the enemy lines from the rear, thus alluding to the classic ‘hammer and anvil’ tactics.

The Phalanx Was More Trained Than Comparable Greek Hoplites

While the traditional Greek hoplites espoused the bravery and lofty ideals of the citizens of an ancient Greek polis, the Macedonian phalanx could be seen as a tight formation of soldiers specifically trained for war and survival. In essence, the sense of professionalism was more widespread in the Macedonian phalanx, where the troops preferred effective army formation over the individual prowess of a soldier, thus foreshadowing the evolution of the future Roman legions.

Such tactical factors could only be perfected on an actual battlefield when supported by a rigorous training regimen. To that end, according to Polyaenus, Philip passionately drilled his soldiers by sometimes forcing them to march over 300 stades (30 miles) in a single day! This was done with the fully adorned equipment of the foot companion, including his unwieldy sarissa spear that was designed as an 18-ft long pike made of cornel wood (during Alexander’s time).

And, in spite of the seemingly rigid formation of the phalanx on the battlefield, Philip preferred the mobility of his army when in the marching phase. This led to the curtailing of many facilities for the officers and soldiers, including the reduction in servants for each man.

This might have resulted in a single servant for ten to sixteen troops, while the soldiers were expected to carry their rations for 30 days additionally. By Alexander’s time, such ‘efficient’ features were complemented by a slew of exercises, drills, and simulated maneuvers – all achieved on a large scale within the training grounds.

Interestingly, one of the ostentatious parade-ground drills was expertly demonstrated by the army of Alexander the Great on an actual battlefield. This was done in a bid to both impress and intimidate the opposing forces of Illyrians in 335 BC (according to Arrian’s Anabasis) –

Then Alexander drew up his army in such a way that the depth of the phalanx was 120 men; and stationing 200 cavalry on each wing, he ordered them to preserve silence, in order to receive the word of command quickly.

Accordingly, he gave the signal to the heavy-armed infantry in the first place to hold their spears erect, and then to couch them at the concerted sign; at one time to incline their spears to the right, closely locked together, and at another time towards the left. He then set the phalanx itself into quick motion forward, and marched it towards the wings, now to the right, and then to the left.

After thus arranging and re-arranging his army many times very rapidly, he, at last, formed his phalanx into a sort of wedge, and led it towards the left against the enemy, who had long been in a state of amazement at seeing both the order and the rapidity of his evolutions.

Members of Alexander’s Army Were Subject to Harsher Discipline

According to Polyaenus, one particular incident related to how a Tarantine cavalry officer was dismissed from Alexander’s army just because he took a bath in warm water. The simple enough reason was – “…for he did not understand the way of the Macedonians, among whom not even a woman who has just given birth bathes in warm water”.

The members of the Macedonian phalanx were also subject to similar codes of conduct, and as such the ultimate power of endowing judgments rested with the king (as opposed to more ‘democratic’ means in other Greek armies).

Such disciplinary actions and punishments, of course, varied in accordance with the nature of the crimes committed. For example, simple insubordination often required the soldier/s to stand in an attentive posture for extended time intervals while wearing his full war panoply – thus mirroring our modern-day military.

However, in some cases relating to the violation of dress codes and inadequate maintenance of weapons, the soldier was required to pay a fine. These monetary sums were specified in accordance with the type of equipment that was deemed to be in an ‘inappropriate’ condition during the routine inspections. But beyond fines and simple chastisements, there was a brutal side to the Macedonian army – especially when the times were tough.

In that regard, the protection of property was a big deal, with the accumulated plunder being divided and specifically allocated to each soldier based on his rank. Oddly enough, such loot and property also included women, and thus those who were carried off as booty were often perceived as the common-law wives of the soldiers.

More intriguingly, the punishments were very strict for seducing women (and thus property) of other soldiers – sometimes even resulting in death sentences. Gruesome forms of executions were also reserved for mutineers – with punishments ranging from being stoned to death, being hurled into rivers, to even being trampled by elephants.

Conclusion – The Psyche and Decline of the Macedonian Phalanx

According to a calculation made by historian Theodore Ayrault Dodge, the infantrymen who had joined Alexander in 336 BC and then embarked on his Asia-bound campaign, had traveled more than 20,870 miles (or 33,400 km) by the time Alexander breathed his last in Babylon (in 323 BC).

So, on average, each of these men had covered an impressive 1,605 miles (or 2,570 km) per year! And, when translated into geographical terms, many of the Macedonian veterans could have claimed to cross a multitude of rivers including the Nile (in Egypt), Euphrates and Tigris (in Iraq), Oxus (in Tajikistan), Syr-Darya (in Uzbekistan), and the Indus (in India).

One Coenus, son of Polemocrates, a veteran Macedonian warrior (promoted to hipparch), aptly presented the conflicted psychology of these grizzled foot companions, via his speech by the Hyphasis River (from Historiae Alexandri Magni, by Quintus Curtius Rufus, circa 1st century AD) –

Whatever mortals are capable of, we have achieved. We have crossed lands and seas, all of them better known to us than to their inhabitants. We almost stand at the end of the world [and] you are preparing to enter another world…That is a program appropriate to your spirit but beyond ours. For your valor will be on the increase, but our energy is already running out.

Look at our bodies – debilitated, pierced with all those wounds, decaying with all their scars! Our weapons are blunt, our armor is wearing out…How many of us have a cuirass? Who owns a horse? Have an inquiry being made on how many are attended by slaves and what anyone has left of his booty. Conquerors of all, we lack everything! And our problems result not from extravagance; no, on war we have expended the equipment of war.

However, beyond the fascinating psyche and incredible fortitude of the Macedonian soldiers, it was ultimately the tactical constraint of a phalanx that led to its decline. Although representing the military backbone of Greek successor states for more than 150 years (after the death of Alexander), the Macedonian phalanx met their match in the Roman legions of the mid-2nd century BC.

As Livy attested, at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC, it was the flexibility of the Roman formations (maniple) that allowed them to engage the stringent phalanx from various directions. These multiple angles of engagements forced the foot companions to abruptly swing around their lengthy spears, thus resulting in a disorderly mass of soldiers – which conclusively defeated the purpose of a tight-packed phalanx. Some have even hypothesized how the uneven terrain might have broken the rigidity of the Macedonian phalanx.

Lastly, modern historians have also theorized how the disciplined phalanx, while being a potent force on the ancient battlefields (in spite of its relative inflexibility), depended on an effective chain of command and supporting cavalry forces. Both of these factors were often missed by the Macedonians and other Greek states when facing the resurgent Romans of the 2nd century BC.

Book References: Alexander the Great at War (Edited by Ruth Sheppard) / Macedonian Warrior (by Ryan Jones, Waldemar Heckel) / Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age (by Peter Green).

Be the first to comment on "The Mighty Macedonian Phalanx of Alexander"