While we have previously talked about cryptic underground temples and magnificently mysterious monuments, the military history side of affairs also has its fair share of baffling, confusing, and even unresolved incidents. So, without further ado, let us take a gander at ten of the most bizarre and odd military encounters (including both wars and battles) ever recorded in the history of mankind.

Contents

The ‘Otherworldly Intervention’ In The Third Mithridatic War

Fought in the time period of 73–63 BC, the Third Mithridatic War was the last and longest of three Mithridatic Wars fought between the allied forces of Mithridates VI of Pontus and the Roman Republic. However, during its initial days, one of the major battles was supposedly stopped by the awesome presence of a meteor.

The odd conflict in question here pitched the Roman general (and senator) Lucius Licinius Lucullus and his 32,000 soldiers directly against the supposedly larger arrayed forces of Mithridates in Phrygia. In spite of the numerical disadvantage, Lucullus decided to engage the enemy, in a bid to drive a tactical outcome that would put the Pontic forces on the defensive.

But as the two enormous lines of soldiers were advancing to meet each other, they were witness to a natural phenomenon on a grand scale. According to Plutarch, the sky suddenly split apart, and a large ‘silvery-hot’ meteor resembling a gigantic hogshead bombarded the battleground between the two armies.

Suffice it to say, the bizarre yet impressive sight frightened most of the innumerable men present in the field. Consequently, both of the rattled forces promptly withdrew from the battle to fight another day, thus resulting in a draw without a single casualty. As for the long-drawn war itself, the Romans ultimately emerged victorious after Pompey the Great succeeded Lucullus as the commanding general.

The Blind Charge at the Battle of Crecy

John of Bohemia, being born into the Luxembourg dynasty in 1296 AD, always had an affinity for the French court. However, by 1311 AD, he was crowned the King of distant Bohemia, after marrying into the ruling Přemyslid dynasty. Unfortunately, John also went blind after suffering from a genetic disease while crusading in Lithuania in 1336 AD.

In spite of his condition, he managed to have a firm grip on his ruling lands, while being also known for his warrior prowess. So, when the French king Philip VI called on his Luxembourgian ally, instead of shirking away, John brought forth his son Charles (who had just been elected King of Germany), and together they participated in the momentous Battle of Crecy in 1346 AD, against the English forces.

And amid numerous debates, one episode of bravery stands out from the defeated French perspective. This incident relates to how blind John tethered his horse with a group of other Bohemian knights. This ‘blind yet bound’ body of armored horsemen decided to boisterously charge into the English ranks but to no avail.

While some records talk about John wildly swinging his sword around the Prince of Wales, the blind king must have ultimately met a gruesome death – as was evidenced by the examination of his battered body. According to later assessments, the King of Bohemia suffered a stab injury to his eye socket (with the pointed weapon being pushed right into his skull) and a stab injury to his chest (that probably penetrated his vital organs). His right hand was also found to be cut off, presumably to steal his precious rings and other kingly items.

Battle of Zappolino

Fought in November 1325, the Battle of Zappolino was probably the only large-scale engagement during the so-called War of the Oaken Bucket between the forces of the Italian towns of Bologna and Modena. As the name of the conflict suggests, the ‘war’ was instigated when soldiers from Modena inconspicuously made their way into Bologna, just to steal a bucket from the city’s main well.

Already being part of the larger conflicts between the Guelphs and Ghibellines, the Bolognese (on the side of the Guelphs) didn’t take the seemingly innocuous incident too kindly; and were further disrespected when the Modena forces (on the side of the Ghibellines) refused to hand over the bucket.

This resulted in the declaration of war by the Bolognese – which was followed up by the invasion force consisting of around 30,000 disparately-armed foot soldiers and aided by around 2,000 Cavaliers. They marched on to the city of Modena, which in turn was defended by only 5,000 infantrymen and 2,000 cavalry forces.

Unfortunately for the Bolognese, their numerically superior forces were routed within just 2 hours of the battle – and the Modena soldiers supposedly chased them all the way to Bologna, while destroying many castles in their path. And in some versions of the events, they even brandished the still ‘unconquered’ bucket as a spoil of war in front of the insulted Bolognese officials. Interestingly, the glorious bucket is still displayed in the main bell tower of the city of Modena (pictured above).

Combat of the Thirty

The Combat of the Thirty (or Combat des Trente) was an odd episode in the Breton War of Succession that took place on March 26, 1351 AD. Fought at a pre-arranged battlefield in Brittany, the encounter pitched two groups consisting of 30 champions and knights against each other, with one side representing the King of France, and the other side representing the King of England.

The challenge was originally issued forth by Jean de Beaumanoir, a captain under the French banner. As befitting of knights, both the French and English fought for a long stretch of time – so much so that even a crowd gathered to watch the bloody contest.

These spectators were even served refreshments, while the knights fought on gallantly. And after several hours of fighting – which caused the deaths of four French and two English knights, the participants called for a time-out. During this short time, the warriors were given medical attention and food.

And after the contest was resumed, the English leader Bemborough was wounded and then killed by his French counterpart. At this critical juncture, the English men decided to form a tight, defensive formation that blunted various French attacks. Finally, a squire named Guillaume de Montauban mounted his horse and charged at the English lines.

This desperate move shattered the enemy’s will; and with seven of their champions being gravely injured, the English finally surrendered. So the French ‘team’ emerged victorious in the macabre contest, with the final tally corresponding to 9 deaths on the English side and 6 deaths on the French. The remaining prisoners were supposedly well treated and released on payment of a small ransom.

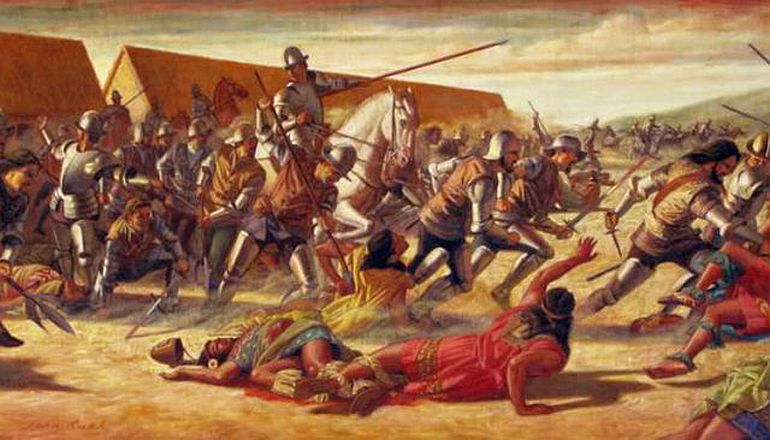

Battle of Cajamarca

The Battle of Cajamarca (taking place on November 16, 1532 AD) is sometimes counted as one of those victories for the Spaniards to win against overwhelming odds. The momentous military encounter in itself pitched around 168 conquistadors (armed with only 12 arquebuses and 4 cannons) under Francesco Pizarro’s command, against 3,000 to 8,000 lightly armed guards of the Inca Emperor Atahualpa.

However, beyond numbers, the battle is notable for the fact that was the very first time that most Incas were witness to the destructive and ‘noisy’ power of gunpowder. The incident started with the Spaniards arriving and concealing themselves within the deserted buildings close to the great plaza of Cajamarca. It is said that some of the Spanish soldiers, knowing about their gravely outnumbered status, even urinated in their breeches out of sheer fear.

In any case, a procession of around seven thousand Incas accompanying Atahualpa arrived later and made their way safely into the town’s square. According to accounts, they were mostly attendants of the emperor who donned their richly attired clothes and ceremonial arms of small axes and lassos. The two party leaders even met with each other.

But things apparently turned sour after the Spaniards tried to convince Atahualpa of their superior religion, and even insultingly (though possibly unintentionally) poured out the ceremonial chicha offered to them in a golden cup. The confusion in semantics further aggravated the Inca emperor, who supposedly yelled ‘If you disrespect me, I will also disrespect you’. Spurred by this seemingly furious tone, the shaken conquistadors fell back to their positions and opened fire at the vulnerable mass of Incas.

This cacophonous effect shocked the lightly-armed attendants who were not familiar with gunpowder. The Spanish forces took advantage of their state of bewilderment and charged through the Inca ranks with only 62 horsemen. With their bells ringing, accompanied by the sound of boisterous gunfire, the cavalry rushed forth and surrounded Atahualpa’s retinue.

After maiming and killing many of the emperor’s personal attendants, Pizarro finally captured the Inca ruler from his litter and thus started his conquest of an empire stretching over 2 million sq km – with just about two hundred soldiers. As for the Battle of Cajamarca itself, the Inca side suffered over 2,000 casualties, while the Spanish forces probably had less than five injuries (or deaths).

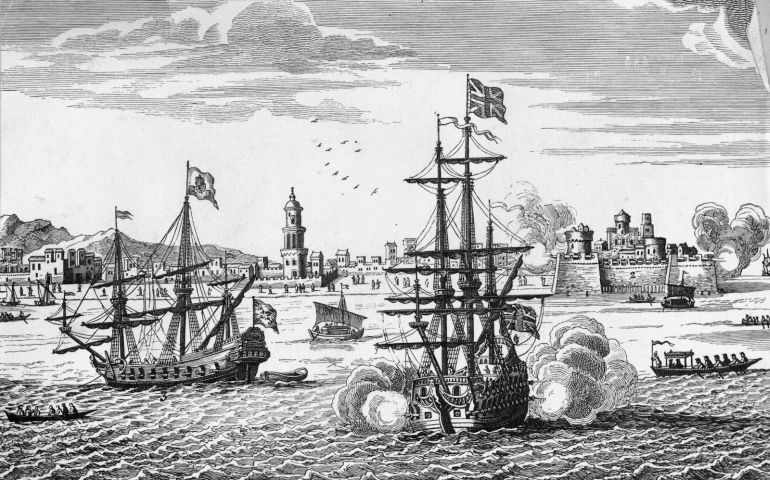

War of Jenkins’ Ear

The odd name of this war fought from 1739 to 1748 AD, was coined by Thomas Carlyle after 110 years of the conflict. The surname ‘Jenkins’ here refers to one Britisher – Robert Jenkins, who was both a captain of a merchant ship and an acknowledged smuggler.

And according to the sequence of events, his ship was boarded by Spanish guards in 1731 AD, and he was subsequently punished by his ear being cut off. This severed ear was preserved and even displayed in front of the British Parliament as a testimony – but was met with a lukewarm response from the Lords.

However, the gimmick was once again used after eight long years, when the opposition parties and the British South Sea Company wanted to instigate a full-blown war with Spain. Such a ‘spurring’ action obviously had its economic reasons, with the primary one being directly related to increasing the trading opportunities of Britain in the Caribbean region.

Moreover, the British companies also wanted to pressurize Spanish officials to keep up their asiento contract, which entailed the permission to sell slaves in Spanish America. Unfortunately, for Britain, their raised forces (that also included for the first time a regiment of colonial American troops) suffered huge losses in the North American theater, which finally culminated in the reversal of their lucrative asiento rights.

The Anglo-Zanzibar War of 40 Minutes

Fought between the United Kingdom and the Zanzibar Sultanate on 27 August 1896, the Anglo-Zanzibar War lasted for 40 minutes. That’s right! Easily the shortest war in the history of mankind, the conflict started when Britain accumulated around 150 sailors along with 900 Zanzibaris (supported by a paltry three cruisers and two gunboats) in the harbor of the Zanzibar Town.

This action was started after the expiration of an ultimatum that stated the removal of the newly crowned ruler of the Zanzibar Sultanate, in favor of a British-choice candidate. On the other side, the Zanzibar Sultanate had around 2,800 soldiers (mostly picked from the civilians) defending their royal palace, while being supported by a few machine guns, artillery pieces, a shore battery, and the royal yacht HHS Glasgow (which belonged to the Sultan and emulated the design of HMS Glasgow).

However, in spite of having lesser numbers, the British side started the engagement by directly bombarding the palace. Within two minutes, the expansive building caught fire, which befuddled the enemy artillery units – thus rendering them ineffective during the fight. This was followed by a naval action that successfully managed to destroy the royal yacht HHS Glasgow (along with two other boats).

Finally, the flag atop the palace was shot down, and a ceasefire was declared just after 40 minutes of engagement. As for results, the Zanzibar Sultanate suffered around 500 casualties, while the British forces sustained only a single injury; while the new sultan fled the country and made his way to German East Africa.

War of the Stray Dog

Often called the ‘Incident at Petrich’, the War of the Stray Dog was a part of the ongoing Greek–Bulgarian crisis in 1925. The incident in question here pertained to a tragic confusion when Bulgarian forces shot and killed a Greek soldier, who was later found to have crossed into the enemy territory while chasing his pet dog. In response, the Greek officials demanded compensation from the Bulgarians.

But unfortunately, tensions were already high between the two nations since the start of the 20th century, with their disputes (and even guerrilla warfare) arising from the possession of Macedonia and Western Thrace. Such a long-standing animosity also resulted in two full-scale wars – the Second Balkan War (1913) and First World War battles on the Macedonian front 1916–18.

Suffice it to say, the Bulgarians refused to pay any form of compensation for their actions. Spurred by these dismissive talks, the Greek forces launched a punitive invasion into the town of Petrich, to punish the soldiers responsible for the murder.

However, on the Bulgarian side, locals rushed to form armed militias that could defend their homes from the Greek incursion. And, by the time the League of Nations had intervened, 50 people had already been killed in the unfortunate military encounter. Later Greece had to pay a ‘reverse’ compensation of around $45,000 for their brutal actions, with their unsuccessful appeal being once again dismissed at the League of Nations.

Battle of Los Angeles

The Battle of Los Angeles, also known as The Great Los Angeles Air Raid, is a baffling episode from the Second World War which occurred between late 24 February to early 25 February 1942, over the city of Los Angeles, California – three months after the unfortunate incident at Pearl Harbor.

According to contemporary sources, after allegedly spotting 25 aircraft in the sky, air-raid sirens were sounded and blackouts were ordered. The 37th Coast Artillery Brigade then began firing at these ‘reported’ aircraft hovering in the sky. The Americans fired from their .50 caliber machine guns and also used 12.8-pound anti-aircraft shells, with the entire engagement costing them over 1,400 shells.

In fact, the retaliation was so massive in scale that the ensuing chaos inadvertently resulted in 5 civilian deaths – with two of the fatalities resulting from heart attacks brought on by the fury and sounds of explosions.

Intriguingly enough, after just a few hours of the alleged raid, a press conference was held by Frank Knox, Secretary of the Navy. He dismissed the entire incident as a false alarm due to anxiety and ‘war nerves’. A contemporary editorial in the Long Beach Independent alluded to the baffling nature of the incident –

There is a mysterious reticence about the whole affair and it appears that some form of censorship is trying to halt discussion on the matter.

Later on, numerous conspiracy theories were concocted, with some hinting at the Japanese capability to launch aircraft raids from their offshore submarines, while others alluding to a secret Japanese base in Mexico. In 1983, the Office of Air Force History put forth their conclusion that the unidentified objects sighted in the sky were meteorological balloons.

And on a more sensational scale, the image published in the Los Angeles Times on February 26, 1942 (see above) has been pointed out by modern-day UFOlogists as alleged evidence of extraterrestrial interference in the episode.

Defense of Castle Itter

‘The enemy of my enemy is my friend’ – an old Indian proverb originating from the 4th century BC was proven to be true by a few German soldiers of the Wehrmacht who had enough of their Waffen SS brethren’s shenanigans.

After 5 days Hitler committed suicide, the veteran 17th Waffen-SS Panzer Grenadier Division continued with their bloody plans to recapture an Austrian castle called Schloss Itter in Tyrol. This castle was used as a special prison for enemy VIPs, and as such imprisoned some famous French personalities, including former prime ministers Édouard Daladier and Paul Reynaud.

A detachment of the SS division arrived on the morning of May 5, 1945, with around 150 men to retake Castle Itter and execute its prisoners. But they were bravely met by a rag-tag defensive force comprising 14 soldiers from the US Army (aided by one Sherman tank), the newly-armed prisoners themselves, and surprisingly 10 German soldiers from the Wehrmacht.

In the ensuing battle, the Sherman tank was used as a makeshift machine-gun outpost but was soon destroyed by an 88 mm gun. And, within just a few hours, the defenders almost ran out of ammunition for their MP-40s.

So a desperate ploy was hatched which involved the tennis legend Jean Borotra (who was then a high-profile prisoner inside the castle) vaulting over the castle walls, gathering information about the German positions, and then sprinting across to the proximate town for calling reinforcements. The desperate tactic seemingly succeeded with reinforcements arriving by 4 pm in the evening; who then defeated the SS forces and took over 100 prisoners from their ranks.

Be the first to comment on "Oddest Military Encounters Recorded in History"