The historical successes of the ancient Roman army had always intrinsically pertained to their ability to adapt and ‘learn’ from their enemies. One of these evolutionary measures related to the adoption of the manipular formations by the 4th century BC. In essence, this brought forth the famed Triplex Acies, a standard combat formation of the Roman legions that entailed three lines of maniples – with the field army spread in a quincunx (checkerboard) pattern.

And the good news from the visual perspective is – Total War enthusiast and YouTuber extraordinaire Invicta has reconstructed this entire battlefield scope in the Rome 2 game engine, and the ‘dynamic’ results are glorious to behold.

The Preceding Years

In fact, though it may sound antithetical, before this time period, the Romans actually fought (for over a century) in formations that replicated the hoplite tactics of ancient Greeks. In any case, traditionally the late 6th century brought forth some sweeping reforms – possibly initiated by the penultimate Roman king Servius Tullius.

The ruler made a departure from the ‘tribal’ institutions of curia and gentes (of the Roman kingdom) and instead divided the military based on the individual soldier’s possession of property. In that regard, the Roman army and its mirroring peace-time society were segregated into classes (classis).

According to Livy, there were six such classes – all based on their possession of wealth (that was defined by asses or small copper coins). The first three classes fought as the traditional hoplites, armed with spears and shields – though the armaments decreased based on their economic statuses. The fourth class was only armed with spears and javelins, while the fifth class was scantily armed with slings.

Finally, the sixth (and poorest) class was totally exempt from military service. This system once again alludes to how the early Roman army was formed on truly nationalistic values. Simply put, these men left their homes and went to war to protect (or increase) their own lands and wealth, as opposed to opting for just a ‘career’ in the military.

The Maniple

Interestingly enough, these socio-political reforms of the ancient Roman society paved the way for stricter measures of recruitment and conscription – which maintained the high quality and discipline expected from the citizen soldiers. Concurrently on the military side of affairs, the 4th-century epoch in Italy was witness to the ascending Romans being pitted against the hardy Samnites.

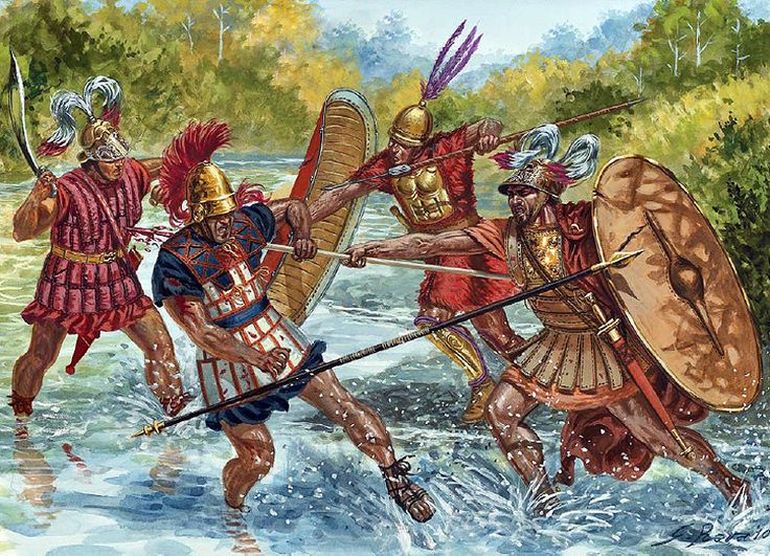

The scope of such conflicts mostly entailed hasty engagements and closed terrains – factors that were not at all conducive to phalanx (hoplite formations) based warfare. And given the Roman penchant for adaptability, their citizen armies seemed to have endorsed newer formations that were more flexible in nature. This change in battle-oriented stratagem was probably in response to the Samnite themselves – and as a result, the maniple formations came into existence (instead of the earlier rigid phalanx).

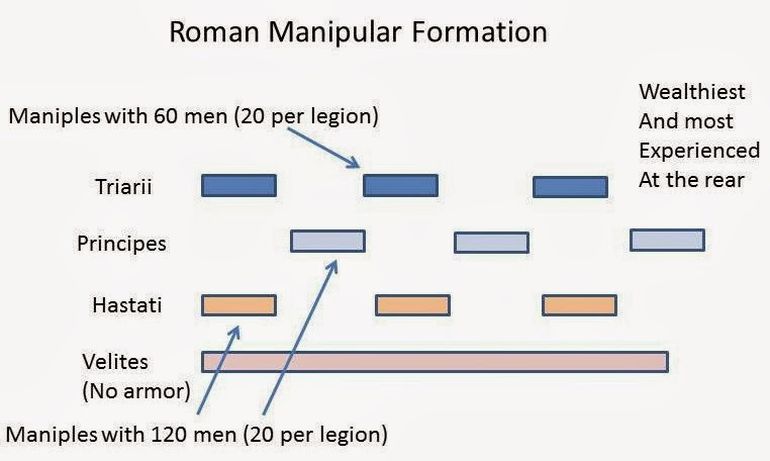

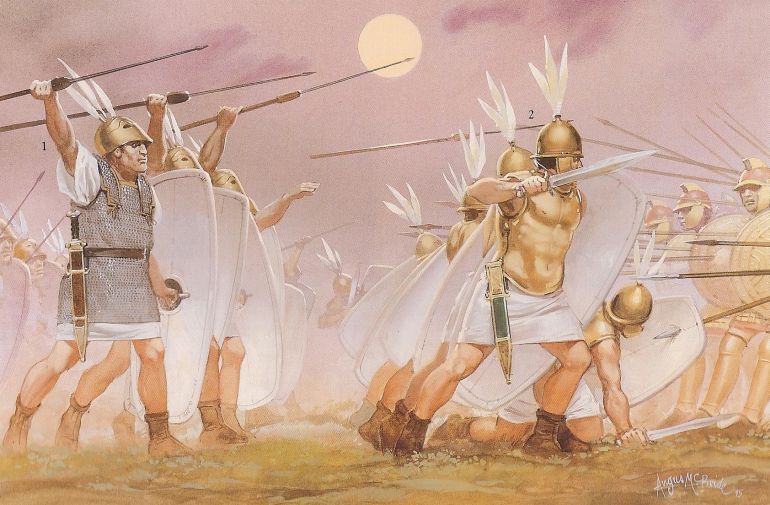

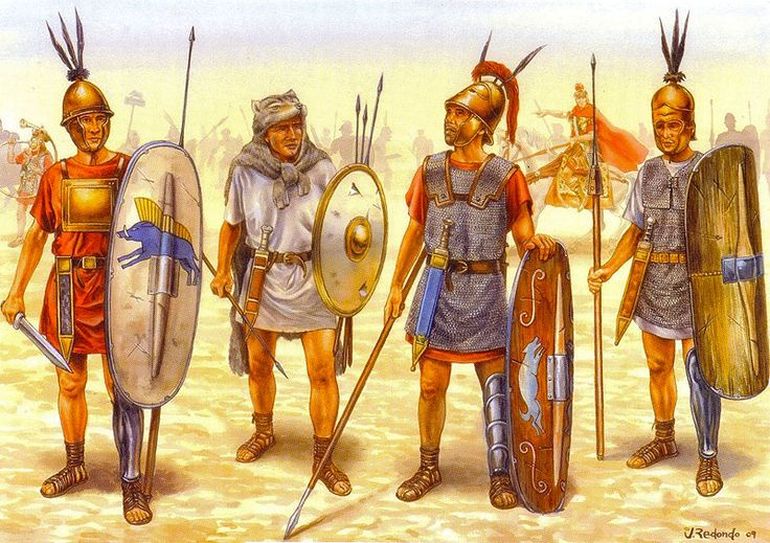

The very term manipulus means ‘a handful’, and thus its early standard pertained to a pole with a handful of hay placed around it. According to most literary pieces of evidence, the Roman army was now divided up into three separate battle lines, with the first line comprising the young hastati in ten maniples (each of 120 men) – armed with swords, pila, and minimal armor; the second line comprising the hardened principes in ten maniples – armed with swords and (possibly) relatively better armor; and the third and last line consisting of the veteran triarii in ten maniples – who probably fought as heavy hoplites (but their maniples had only 60 men).

Additionally, these battle lines were also possibly screened by the light-armed velites, and further flanked by equites horsemen. Now if we go back to Livy’s description of the classis, we can certainly draw similarities between the economic classes and their corresponding statuses within the manipular system.

For example, the primary three classes were now divided into the main fighting arm – and they comprised the hastati (the young and relatively poor); the principes (the experienced and belonging to the middle class); and the triarii (the veterans and relatively well-off citizens). They were complemented by the equites (cavalrymen who belonged to the richest sections of Roman society) and the contrasting velites (the lightly armed skirmishers who were the poorest).

The Societal Connection

Beyond the change in battlefield formations, we should also consider the dynamic logistical scope of the Roman Republic in the late 4th century. By this time period, the Romans were successful in subjugating many of the Italic states, and these defeated enemies in turn inflated the availability of manpower for the ascending Republic. In that regard, many of the captured towns were offered full citizenship, while the Romans also initiated a new form of ‘pseudo’ citizenship.

Known as civitas sine suffragio, this status when offered to a ‘new’ citizen, made him liable for taxation and military service, but without the right to vote. The previously rival regions of Campania (including the cities of Capua and Cumae) were assigned to this seemingly harsh category. Furthermore, many ‘original’ Roman citizens were offered new lands to settle via the allocation of the pastures and farmlands of the defeated foes.

This surely must have boosted the economic capacity of some poorer Romans, thus making them liable for military service. So in a nutshell, the manpower of the Roman Republic increased manifold by this era – and this would have made the adoption of flexible and bigger battlefield formations (maniple systems) far easier to achieve.

In fact, this ambit of economic status mirroring the citizen’s military liability was the mainstay attribute of the Roman Republic army, circa 3rd century BC – since it was pretty much assumed that more a man was richer, the more his incentive (and motivation) should be to acquire proximate lands through conquering and campaigns.

To that end, the citizen militia (or soldiers) of Republican Rome were levied and then assembled in the Capitol on the day that was proclaimed by the Consuls in their edictum. This process was known as dilectus, and it only allowed men who owned properties valued at over 11,000 asses. Intriguingly enough, the men volunteers were arranged in terms of their similar heights and age.

This brought orderliness in terms of physical appearance, while similar equipment (if not uniform) made the organized soldiers look even more ‘homogeneous’ in unison with the maniple system.

The Battlefield Scenario

The video does a great job of explaining how the Triplex Acies might have worked in an actual tactical scenario. And the first point to note here is that in spite of being less rigid than the traditional phalanx, the maniple system and the associated checkerboard pattern (quincunx) did require a tremendous degree of discipline on the part of the Roman soldiers.

To that end, it was this sheer scope of organization that was possibly ‘flaunted’ in front of the enemy, thus psychologically rattling the opposing forces by both impressing and intimidating them.

But beneath the veneer of discipline and organization, it was the intrinsic flexibility offered by the Triplex Acies of the maniple system that made it such a favored formation among the Romans. Suited to most terrain types, the quincunx pattern would have surely boosted the morale of the first lines of hastati, as these young men knew that they were bolstered in their rear ranks by the more experienced troops of the Republic.

More importantly, these maniple formations allowed for a battlefield system of reserves to be deployed for better tactical advantage. For example, when the front-lining hastati was drained of his strength during the heat of the battle, he could fall back upon the reserve lines of the principes.

The well-armored veterans were then deployed forward in a cyclic manner – thus resulting in a fresh batch of troops countering the exhausted (and usually less organized) enemy. This simple yet effective tactic changed the outcome of many a battle in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC.

Video Source: YouTube (Invicta)

Sources (for the article): MIT.edu / UNRV / Britannica / Classics.UPenn

Book References: Rome and Her Enemies (Editor Jane Penrose) / Roman Legionary 58 BC – AD 69 (By Ross Cowan) / Caerleon and the Roman Army (By Richard J. Brewer) / The Roman Army from Caesar to Trajan (By Michael Simkins)

Be the first to comment on "Animation Showcases the Roman Maniple Army Formation ‘Triplex Acies’ in Action"