Introduction

Almost as famous as the Knight Templars and Hospitallers, the Teutonic Knights and their popular imagery of extravagant horned helmets on steel-clad horsemen have stoked the fascination of many a history aficionado. And though the latter was possibly only used for ceremonial purposes, there is without a shred of doubt a unique historical scope when it comes to the legacy of this medieval military order. Much of it perhaps has to do with the fact that the Teutonic Order made its military mark in the mysterious lands of north-eastern Europe, as opposed to the renowned Holy Land.

It should also be noted that at the same time these ‘knights’ were more successful in establishing a full-fledged, economically viable monastic state (Ordensstaat) than their peer Crusader orders like the Templars and Hospitallers. So without further ado, let us take a gander at the turbulent history of the Teutonic Knights – the military bane of pagan Europe.

Contents

The Establishment of the Teutonic Order

From Hospital to Near Extinction

While the Third Crusade was supposed to be the glorious military feat to reconquer the Holy Land from Saladin, the campaign though partly successful ended in a disaster for the Imperial forces of the Holy Roman Empire. This was because of the untimely death of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa before his massive army (comprising 3,000 knights and other troops) could approach the contested areas.

So only a remnant of his followers took part in the Crusade and subsequently established a field hospital after the siege of Acre. This hospital was later granted recognition from the Papacy, which established the organization as a military order, christened as Fratres Domus Hospitalis Sanctae Mariae Teutonicorum (Brethren of the German Hospital of St Mary), which later became the Teutonic Knights.

Like other crusading orders, the Teutonic Knights (though not as powerful as the Templars and the Hospitallers in the Levant), held small parcels of land and strongholds all throughout the Holy Land, with their primary headquarters pertaining to the suburb of Montfort in the region of northern Palestine. However, in 1244 AD, many of the military orders suffered a fateful defeat at the hands of the Ayyubids, with the Teutonic Knights losing 397 of their 400 actual knights in the encounter.

In spite of this massive reversal, the Teutonic Knights continued to exert influence in the nearby Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia – possibly to counter the Templars from the neighboring Principality of Antioch, thus suggesting how political rivalry was present even between Crusader religious orders. However the fall of Acre in 1291 AD finally symbolized the end of their crusading endeavors in the Holy Land, and the Teutonic Order then focused its attention towards the pagan regions of Europe itself.

The Hungarian Affair

Interestingly enough, after just a few years of its founding, the Teutonic Order also had the opportunity to establish itself in the district of Burzenland (Terra Borza) in Transylvania, at the behest of the Hungarian king Andrew II. Burzenland was a wild mountainous region inhabited by diverse people including Vlachs, Slavs, Pechenegs, and even the raiding Kipchaks.

Suffice it to say, the Hungarian overlords were interested in maintaining a semblance of authority over the multifarious subjects of this frontier district. And thus the Teutonic Knights were invited to control the mountain passes (as bulwarks against the nomadic Kipchak raids).

However while the Teutonic Order was given relative autonomy in the functioning of its troops in the region, the Hungarian king prohibited the knights from erecting stone-based fortifications – probably because he didn’t want the order to be a militarily independent faction with strong political influence in the area. But the Teutonic Knights broke their agreement and started constructing stone-based castles, and at the same successfully repelled various Kipchak raids.

Thus the situation became complex for the Hungarian monarch, who actually proceeded to gift even more ‘non-Hungarian’ lands to the order as a reward for their effectiveness, in spite of their perceived ‘insolence’.

But the unique political scope was extinguished in 1225 AD after many Hungarian barons and Vlach subjects (who were Orthodox Christians) were rebellious due to the rising power of the Catholic Teutonic Knights. As a result, the knights were unceremoniously expelled from Hungary, which finally propelled them to establish an independent power base of their own.

The Baltic Endeavor of the Teutonic Knights

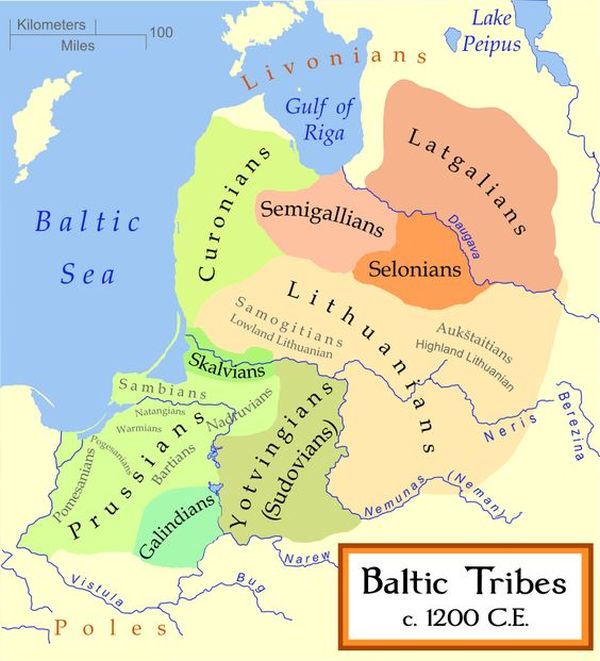

Ironically the loss of opportunity in Hungary actually led to the Teutonic resolve to institute their own stronghold – an opportunity given to them by Konrad I of Masovia (who hailed from Poland’s Piast dynasty). The Duke was fighting his own expansionist wars in the adjacent pagan territory of the Prussians (not to be confused with their latter-day counterparts). Although his military efforts were coming to naught with enemy raids that even threatened his own residence at the Plock castle.

Frustrated by the Prussian presence, the Duke finally invited the embittered Teutonic Knights in 1226 AD to fight his foes. However, the military order only agreed to Konrad’s request on the condition that the Duke offered them a small territory based around the frontier town of Kulm.

Thus the Teutonic Knights finally established their own independent stronghold in the very heart of Europe, and the Baltic chapter unraveled through numerous political acts, military actions, horrendous crimes, and shifting alliances. In the direct aftermath, the Teutonic Order was successful in extinguishing the Prussian state after almost 50 years of brutal warfare, and consequently, the order actually ruled Prussia under charters issued by the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor as a sovereign monastic state.

As for the bigger picture, the Baltic frontier opened up a power struggle between various European and Eurasian factions, including Lithuanians, Russians, Livonians (comprising Estonia and Latvia), Swedes, Catholic Poland, and even the Golden Horde Mongols and Tartars.

Organization and Composition of the Teutonic Knights

The Hochmeister and other Seniors

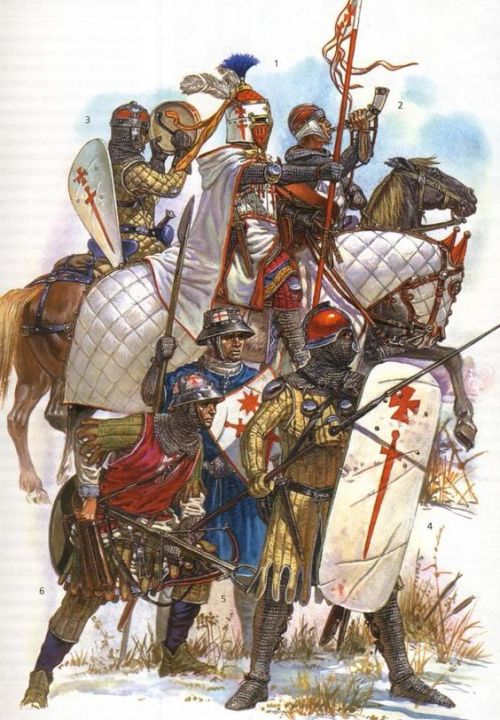

Unsurprisingly, when it came to the organization of the Teutonic Order, there were many similarities to other Crusader orders like Templars and Hospitallers. To that end, the upper-most administrative strata comprised the Hochmeister (literally ‘high master’) who were the Grand Masters of the Teutonic Knights, accompanied by representatives of the Ballei (administrative provinces) and five other senior officers whose titles ranged from Treasurer, Supreme Marshall to even Supreme Draper.

Interestingly enough, the election of Hochmeister took a democratic route that was quite unparalleled in medieval times. It started with the nomination of a brother-knight as the elected leader, and he proceeded on to elect his companion, and these two knights, in turn, elected the third member, and so on until 13 knights were chosen for the electoral college (theoretically representing the majority of the Teutonic Order members). These thirteen members were finally responsible for electing the Grand Master.

The Paradox of ‘Lowly Knights’

Interestingly enough, in spite of some correlations with other European military orders in terms of organization, the main difference between the Teutonic Knights with its peer orders ironically pertained to the ‘knights’ themselves. This was mainly because of the unique social strata of ministeriales present in medieval Germany – from where most of the knights of the Teutonic Order were recruited.

In fact, in the 12th century AD, many of these ministeriales were identified as ‘servants’ (Dienstmann). In essence, while the early ministeriales formed a military class of their own, their theoretical status was akin to those of serfs. To that end, historically the very first European knights also probably came from a peasant background, as opposed to their perceived noble bearings.

Now of course over the course of the next decades or so, the social status of the ministeriales took a significant boost, thereby mirroring the rise of European knights in both military and political roles. By the mid-13th century, many of the Dienstmann were actively employed as household knights, thus lending credence to their path to being noblemen.

By the 14th century, the association of a German knight with serfdom almost completely disappeared, and as such many of these military men emerged as the Ritterschaft, the autonomous class of knights in the German provinces who mainly formed the lower nobility.

The ‘Half-Brethren’ and ‘Sword Brethren’

The full members of the Teutonic Order were also accompanied by the Halb-bruder (half-brother), who preferred to wear grey mantles instead of white, and thus were also called Graumantler. It is probable that many of these half-brethren didn’t take their rigorous monastic vows, which in turn allowed them to marry.

As for the military side of affairs, the Halb-bruders were possibly employed as heavy infantry, though their main practical contribution entailed carrying out agricultural tasks within the Teutonic stronghold. Moreover, the order also employed a separate ‘servant’ class known as Diener, who were mainly inducted as an armed garrison and functioned as crossbow militia or even mounted infantrymen.

Now since we are talking about European medieval military orders, the third bishop of Riga was known for establishing the separate Livonian Brothers of the Sword, possibly in 1204 AD. Unfortunately for the organization, it met a heavy defeat in 1236 AD (or 1238 AD) at the hands of the combined forces of Samogitians and Semigallians (both Lithuanian tribes) in what is known as the Battle of Saule.

One of the major fatalities of the encounter included the order’s Grandmaster (along with 60 other high-ranking knights), and as a result, the remaining forces were finally merged with the more powerful Teutonic Order.

After the momentous merging episode, they were known as the Livonian Order or simply the ‘sword brethren’ (or Schwertbrüderorden in German). Interestingly enough, while the aforementioned battle marked the eclipse of the Livonian Brothers, the Teutonic Order stood to gain an additional 100 knights, 500 mounted sergeants, 400 German vassal soldiers, 700 mercenaries, and possibly over 4,000 auxiliaries, along with six castles and a plethora of smaller territories in Livonia.

Other Teutonic Order Members

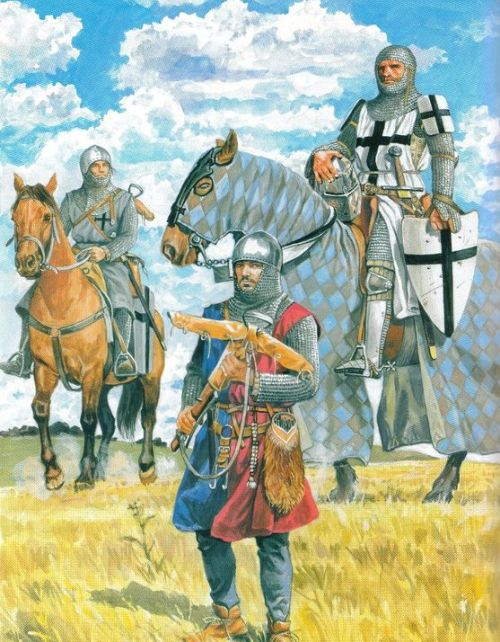

Once again, like many of their contemporary military orders, the soldiery of the Teutonic Knights was not only dependent on the namesake knights (who always formed a minority of the available forces) or even the half-brethren. In fact, a major source of military manpower came from the defeated Prussians, especially their ‘Germanized’ nobility and freemen (Witinge) who adopted many of the Western European armor types and styles of warfare.

And while they were not allowed to formally join the order, their native tactics were often instrumental in countering the still pagan Lithuanians, circa 13th century AD. Additionally, there were also the Prussian auxiliaries who fought as light cavalry, complemented by other native chiefs who hailed from Livonia and Estonia.

Interestingly, the forces of the Teutonic Order were bolstered by the ‘secular’ settler knights who were endowed with lands, castles, and tithes by the orders of the Hochmeister, in return for the conventional feudal military service of the contemporary period.

The order also welcomed ‘occasional’ crusaders who actually volunteered to join the Teutonic ranks and perceived it as part of their religious duty. These men typically came from the high nobility spread across Europe, with one pertinent example relating to King John of Bohemia, who went blind after suffering from a genetic disease while crusading in Lithuania in 1336 AD.

And finally, like most late-medieval armies, the Teutonic Order did make use of mercenaries, including the famed Genoese Crossbowmen. In fact, their overgrowing reliance on mercenaries in the early 16th century (like dedicated hand-gunners) led to the rise of taxation throughout their controlled territories.

The Military and Economic Clout

The Warrior Traders

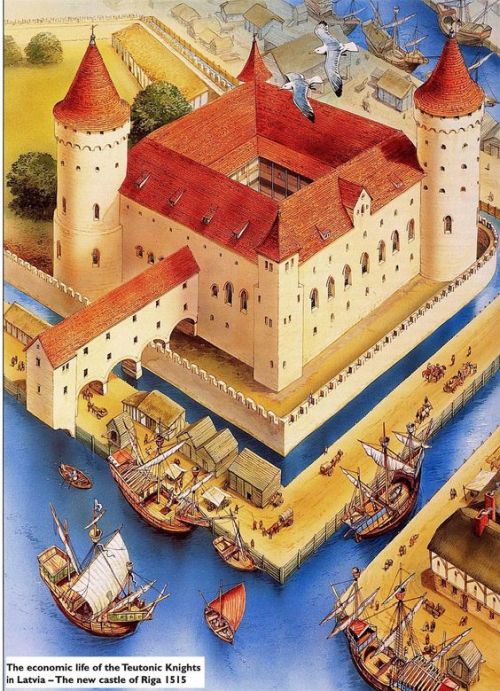

Yet another similarity shared between the medieval Crusading orders was their ability to sustain commercial avenues while conducting military campaigns and punitive actions. To that end, the very high cost of warfare made it crucial to have economic backing.

In the case of the Teutonic Order, while their main power was based in the strongholds of Germany, many of the brethren had the task of fueling their economy in the newly captured territories of Prussia and the Baltic.

As a result, many of the knights also took up the mantle of astute businessmen who often tended to be experts in trading commodities like wheat, hides, and wool. Over time, many of the Teutonic Order brethren played a vital commercial role in maintaining long-distance trade routes that stretched from Europe to the Middle East via the Balkans and Greece.

Another important source of revenue (and manpower) for the order came from the colonizers who mainly hailed from the proximate regions of Germany. Attracted by a range of low taxation privileges, cultivable lands, and even (sometimes) the requirement of relatively light feudal service, these settlers provided the much-needed economic boost to the subjugated lands.

And even beyond trading and settling, the Teutonic Order also focused on the industrial capacity of a region in terms of production. To that end, the manufacturing scope of commercial products like horses, wool, leather, wheat, lime, and salt, was kept under strict regulations via guilds established in the towns. In essence, the Teutonic economy was controlled and boosted by the commercial trifecta of trade, industry, and agriculture.

The Strategy of Fortifications

It should be noted that, unlike most medieval European battlefields, the war zones of the Baltic were afflicted by freezing winter conditions that could even decimate entire armies of nominally clad infantrymen by its baleful range of blizzards and squalls.

These fierce wintry conditions were further exacerbated during the summer times by unexpected floods from the seasonal thaws, which in turn made the extensive marshy areas inconvenient for horse grazing. In essence, the strategy of securing victories in such scenarios not only entailed defeating enemies on the battlefield but also required armies to preserve logistical lines of supply and provisions.

And that is exactly where the Teutonic Knights used their advantage by preferring to build stone castles and imposing strongholds in the newly conquered regions. For example, in the later campaigns of Prussia (by the second half of the 13th century), the order employed the long-drawn strategy of gradually pushing the enemy and establishing fortifications in these hard-won regions.

Consequently, this military scope established a tight network of defensive quarters (stocked with provisions and inhabited by settlers – as we mentioned before) where their armies could retreat or take refuge during unfavorable circumstances. At the same time, these gathered armies bolstered by supplies, with their core comprising armored cavalry and dedicated crossbowmen, could speedily strike at the foe when the opportunity presented itself.

The Economy of ‘Human’ Booty

The bitter truth of a medieval battlefield often translated to the merciless massacre of wounded soldiers or the unconditional slaughter of fleeing enemies. Objectively, such brutal measures were employed not to fit any sadistic narrative, but rather as practical actions that could immediately force the outcome of a hard-won battle and its political aftermath. However, since we are talking about the ‘practicality’ of the situation, there were also occasions when opposing soldiers were captured and sold into slavery.

In fact, in the Baltic Crusades, humans were one of the important forms of booty for not only the Teutonic Order but also its Lithuanian foes. Furthermore, the heinous scope was not only limited to capturing troops on the battlefields but also extended to mass abductions of women and children in the fringe villages and settlements – that may have resulted in hundreds of thousands of slaves who were seized from their homelands.

Most of them were used as forced labor in stone-walled cities and the agricultural villages governed by the Teutonic Knights. During rare parleys, captured enemy soldiers were also ransomed, especially if the foes came from higher ranks of nobility.

Honorable Mention – Rigorous ‘Poverty’ Laws and Codes

In spite of their penchant for commercial endeavors, the Laws and Customs of the Teutonic Order were intrinsically tied to the notion of communal ‘poverty’. In fact, the brothers were not even allowed to keep private chests where they could keep their personal items and clothes. The seemingly strict law concerning the vows of poverty also extended to prohibiting the possession of money and the exchange of goods between themselves on the pretext of profiting.

Online Sources: Imperial Teutonic Order (link here) / Britannica / New Advent

Book References: Teutonic Knight 1190–1561 (By David Nicolle) / The Teutonic Knights: A Military History (By William L. Urban)

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "Teutonic Knights: The Turbulent History of the Military Order"