Introduction

Starting out as a backwater inhabited by cattle rustlers who made their camps and rudimentary dwellings among the hills and the swamplands, Rome emerged as the eternal city that was the focal point of an ancient superpower marshaling its influence from the mines of Spain to the sands of Iraq. And while the incredible feat wasn’t ‘achieved in a day’, the sheer scope of Roman ascendancy was fueled by the ancient juggernaut of a military establishment.

In a space of less than a millennium, the Romans eclipsed their powerful Italic neighbors; survived the sacking of Rome itself; possibly lost one-twentieth of their male population in a single battle, fought numerous economy-shattering civil wars – and yet managed to carve out an empire that has been termed as the ‘supreme carnivore of the ancient world’ (by historian Tom Holland). In all of these, the singular factor that played a crucial role was the Roman military, an institution driven by the exploits of the determined and trained ancient Roman soldier.

Now our popular culture tends to identify the Roman soldier as the quintessential Roman legionary of the first centuries of the common era. And while part of this scope holds true, since the Roman Empire did reach its greatest extent in the early phases of the 2nd century AD, the notion of a Roman soldier is obviously not a static entity that remained unchanged over the centuries – in terms of both his social status and the arms he bore.

Keeping that in mind, let us take a gander at the evolving nature of the ancient Roman soldier over a period of almost a millennium, from circa the 8th century BC to the 3rd century AD.

Contents

- Introduction

- The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa late 8th century BC – early 6th century BC

- The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa late 6th century BC – early 4th century BC

- The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa late 4th century BC

- The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa 3rd century BC – late 2nd century BC

- The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa 1st century BC

- The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa 1st century AD – 2nd century AD

- The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa 3rd century AD

- Timelapse Showcases The Evolution of a Roman Soldier from circa 9th century BC to 6th century AD

The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa late 8th century BC – early 6th century BC

While it may come as a surprise to many, the Roman army equipment’s archaeological evidence ranges far back to even the 9th century BC, mostly from the warrior tombs on Capitoline Hill. As for the literary evidence, they mention how the earliest Roman armies were recruited from the three main ‘tribes’ of Rome.

In any case, the transition of the Roman army from ‘tribal’ warriors to citizen soldiers was achieved in part due to Roman society and its intrinsic representation (with voting rights) in the Roman assembly.

To that end, the early Romans almost entirely depended on their citizen militia for the protection and extension of the burgeoning faction’s borders. These militiamen were simply raised as levy or legio – which in turn gives way to the term ‘legion’. In essence, the so-called legions of early Rome were ‘poor’ predecessors to the uniformly-equipped and disciplined soldiers of the later centuries.

In fact, the legions of early Rome were conscripted only as part-time soldiers and had their main occupation as farmers and herders. This stringent economic system prevented them from taking part in extended campaigns (that hardly went beyond a month), thus keeping military actions short and decisive. Moreover, these legions had to pay for their own arms and armaments – which at times was compensated only by a small payment from the state.

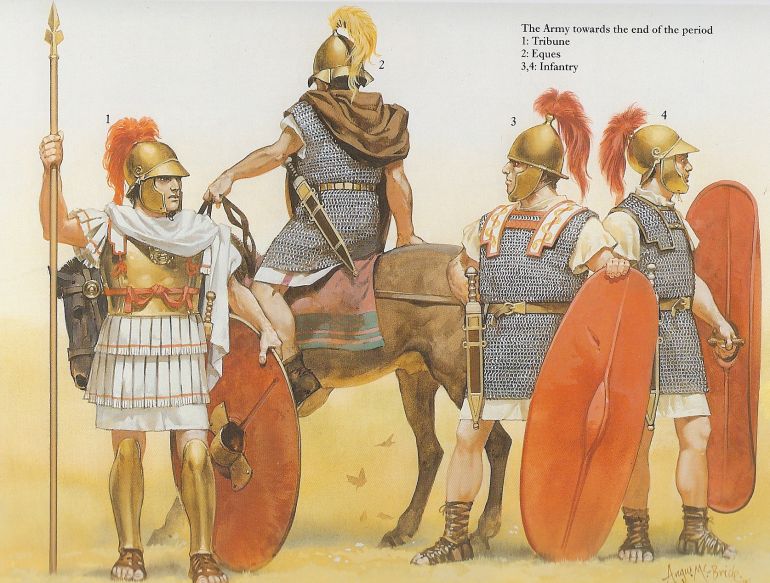

The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa late 6th century BC – early 4th century BC

The popular notion of the Roman army fighting in maniples is a correct one if only perceived during the later years after the 4th century BC. However, in the preceding centuries, the Roman military system was inspired by its more-advanced neighbor (and enemy) – the Etruscans.

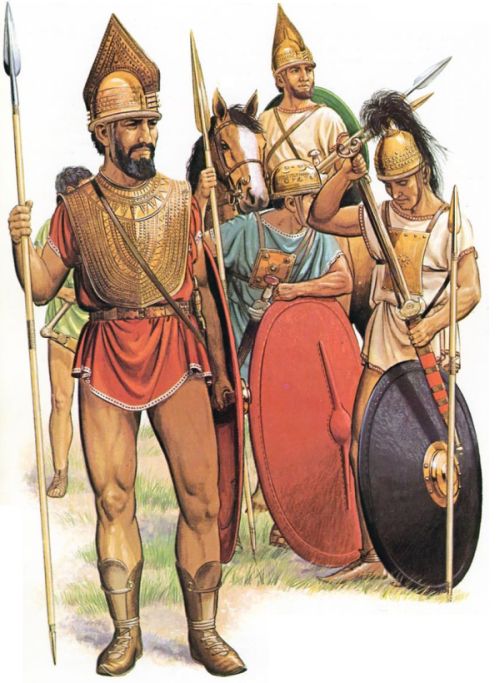

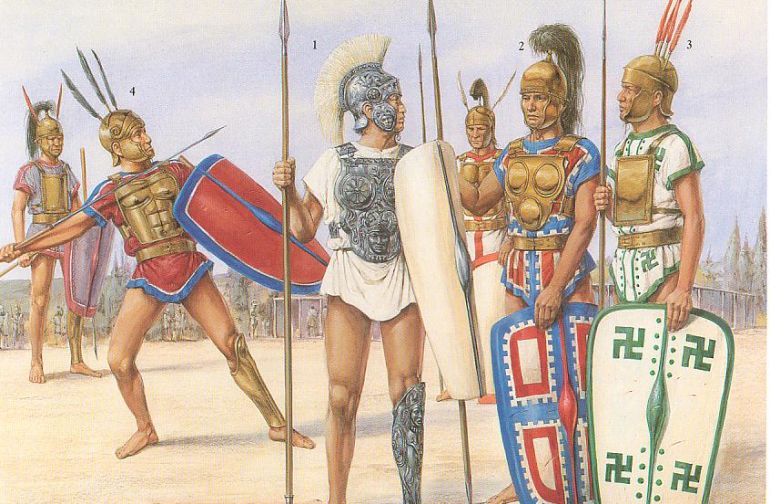

In fact, the hoplite tactics of mass formation of men fighting with their shield and spear were already adopted by the Greeks by 675 BC and reached the Italy-based Etruscans by the early 7th century BC. The Romans, in turn, were influenced by their Etruscan foes and thus managed to adopt many of the rigid Greek-inspired formations along with their arms.

As per historical tradition, the very adoption of the hoplite tactics was fueled by the sweeping military reforms undertaken by the penultimate Roman ruler Servius Tullius, who probably reigned in the 6th century BC. He made a departure from the ‘tribal’ institutions of curia and gentes and instead divided the military based on the individual soldier’s possession of the property. In that regard, the Roman army and its mirroring peace-time society were segregated into classes (classis).

According to Livy, there were six such classes – all based on their possession of wealth (that was defined by asses or small copper coins). The first three classes fought as the traditional hoplites, armed with spears and shields – although the armaments decreased based on their economic statuses.

The fourth class was only armed with spears and javelins, while the fifth class was scantily armed with slings. Finally, the sixth (and poorest) class was totally exempt from military service. This system once again alludes to how the early Roman army was formed on truly nationalistic values. Simply put, these men left their homes and went to war to protect (or increase) their own lands and wealth, as opposed to opting for just a ‘career’.

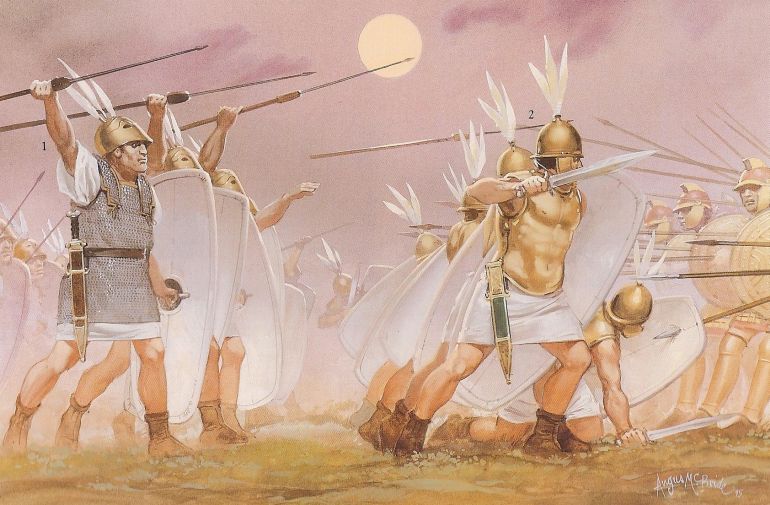

The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa late 4th century BC

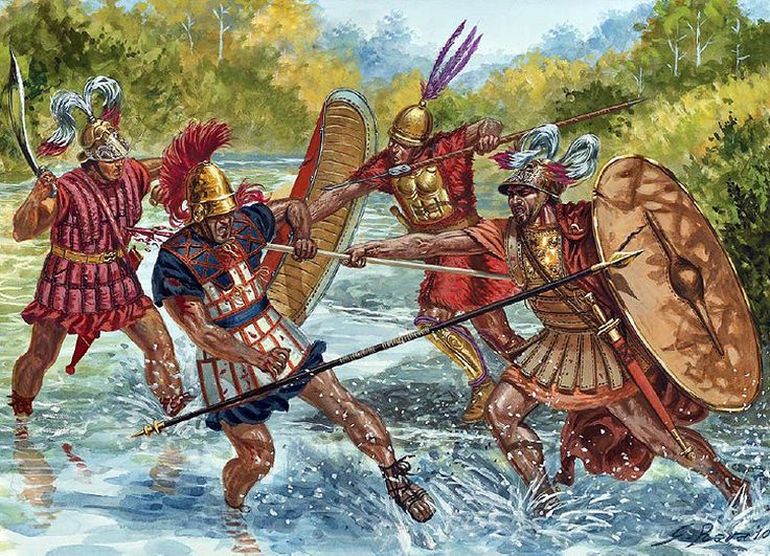

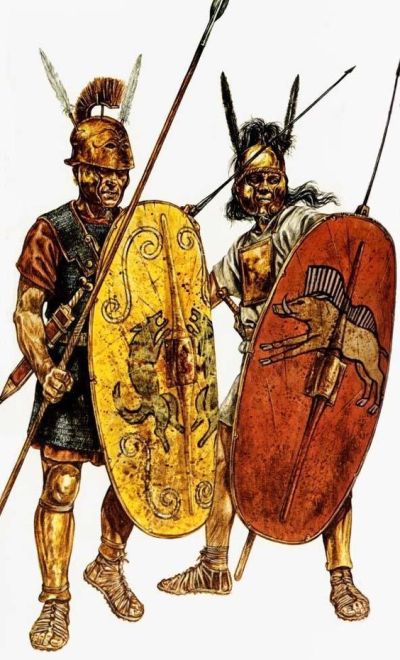

The greatest strength of the Roman army had always been its adaptability and penchant for evolution. As we mentioned before how the early Romans from their kingdom era adopted the hoplite tactics of their foes and defeated them in turn.

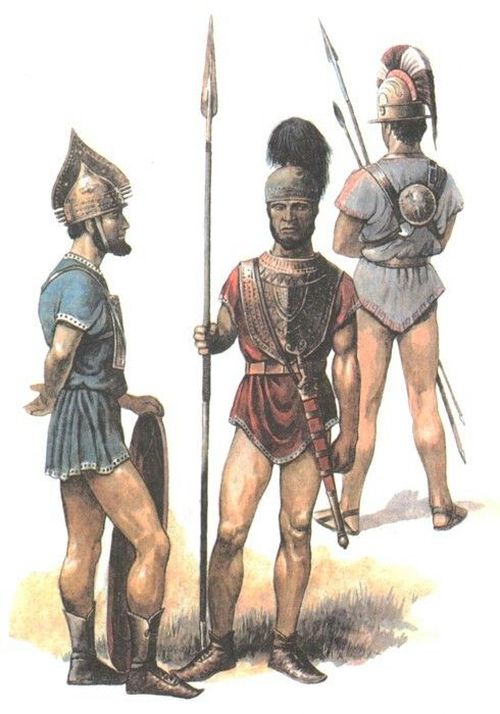

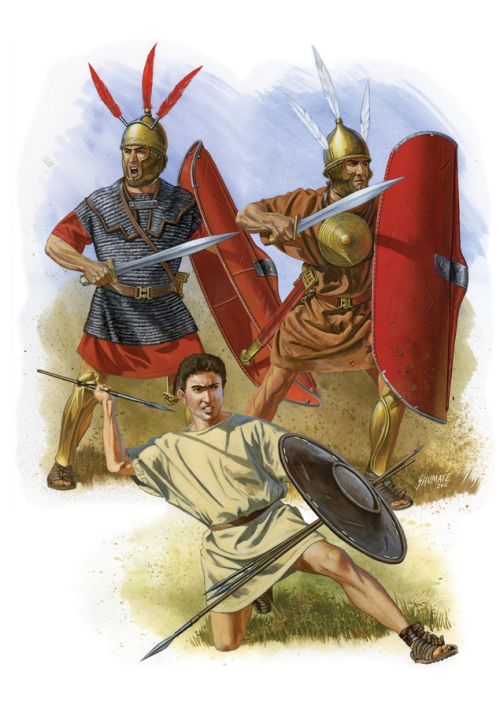

However, by the time of the First Samnite War (around 343 BC), the Roman army seemed to have endorsed newer formations that were more flexible in nature. This change in battlefield stratagem was probably in response to the Samnite armies – and as a result, the maniple formations came into existence (instead of the earlier rigid phalanx).

The very term manipulus means ‘a handful’, and thus its early standard pertained to a pole with a handful of hay placed around it. According to most literary pieces of evidence, the Roman army was now divided up into three separate battle lines.

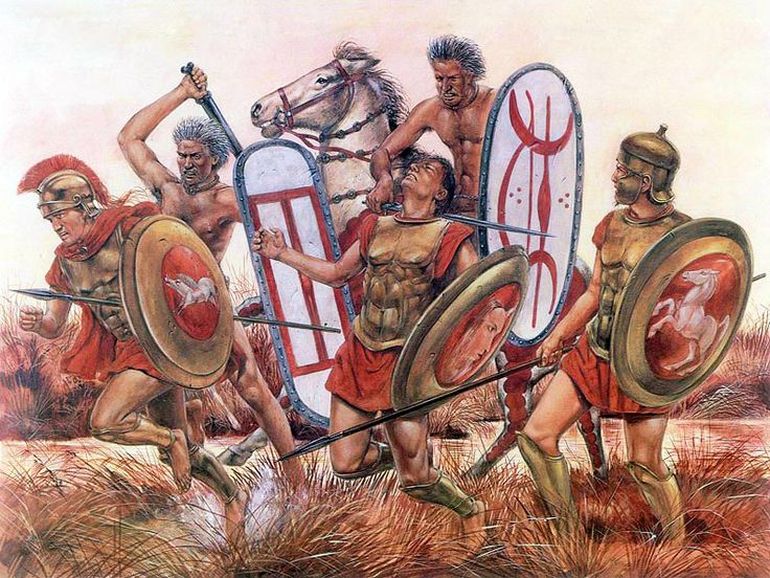

The first line comprised the young hastati in ten maniples (each of 120 men); the second line comprised the hardened principes in ten maniples; and the third and last line consisted of the veteran triarii in ten maniples – who probably fought as heavy hoplites (but their maniples had only 60 men). Additionally, these battle lines were also possibly screened by the light-armed velites, who mostly belonged to the poorer class of Roman civilians.

Now if we go back to Livy’s description of the classis, we can certainly draw similarities between the economic classes and their corresponding statuses within the manipular system. For example, the primary three classes were now divided into the main fighting arm – and they comprised the hastati (the young and relatively poor); the principes (the experienced and belonging to the middle class); and the triarii (the veterans and relatively well-off citizens).

They were complemented by the equites (cavalrymen who belonged to the richest sections of Roman society) and the contrasting velites (the lightly armed skirmishers who were the poorest).

The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa 3rd century BC – late 2nd century BC

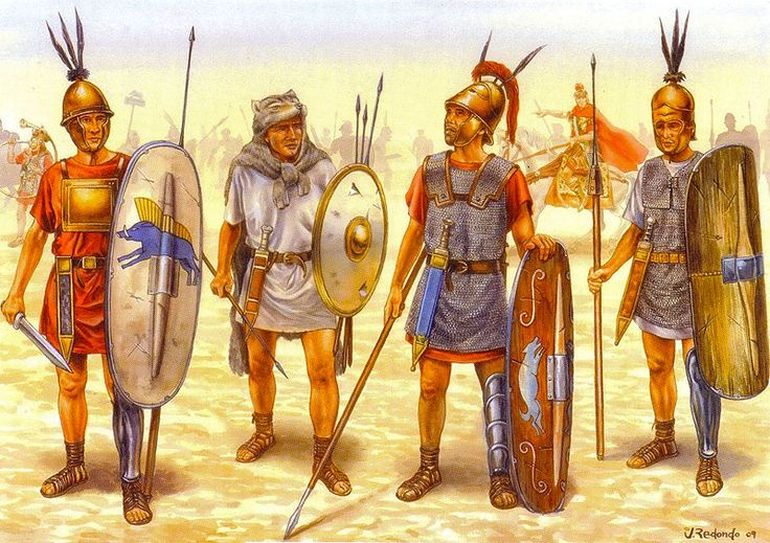

The military overhaul, indicating the transition from phalanx formations to manipular ones, is sometimes referred to as the Polybian reform (especially in the post-290 BC period). By this time, the citizen militia (or soldiers) of Republican Rome were levied and then assembled in the Capitol on the day that was proclaimed by the Consuls in their edictum.

This process was known as dilectus, and interestingly the men volunteers were arranged in terms of their similar heights and age. This brought orderliness in terms of physical appearance, while similar equipment (if not uniform) made the organized soldiers look even more ‘homogeneous’.

The Roman army recruits also had to swear an oath of obedience, which was known as sacramentum dicere. This symbolically bound them with the Roman state, their commander, and more importantly to their fellow comrade-in-arms. In terms of historical tradition, this oath was only formalized before the commencement of the Battle of Cannae, to uphold the faltering morale of the Hannibal-afflicted Roman army.

According to Livy, the oath went somewhat like this – “Never to leave the ranks because of fear or to run away, but only to retrieve or grab a weapon, to kill an enemy or to rescue a comrade.”

However, in spite of oaths and morale-drumming exercises, the bloody day of the Battle of Cannae accounted for over 40,000 Roman deaths (the figure is put at 55,000 by Livy, and 70,000 by Polybius), which equated to over 80 percent of the Roman army fielded in the battle.

Now, according to modern estimation, the male population of Rome circa 216 BC was around 400,000. So, considering the number of casualties at the Battle of Cannae, the baleful figures pertained to 5 to 10 percent of the total number of Roman males in the Republic (considering there were also Italic allies present in the battle) – with all the casualties occurring in a single day!

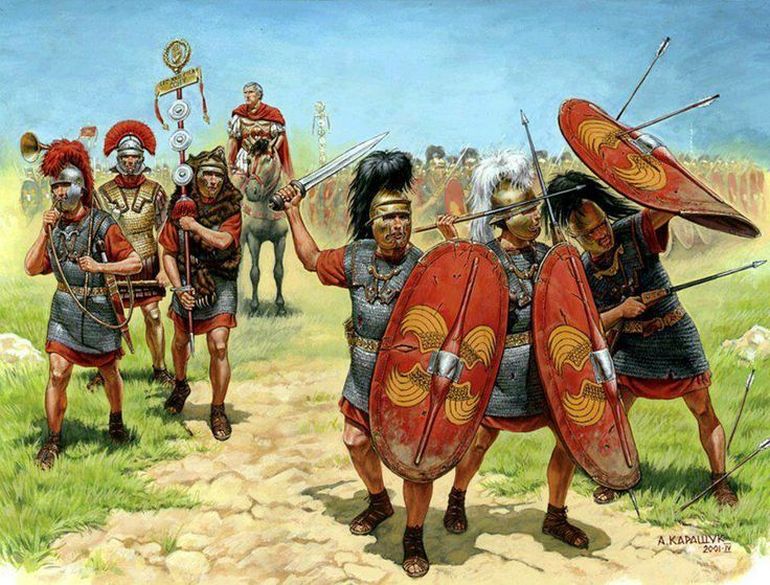

The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa 1st century BC

The last phase of the Roman Republic was marked by yet another military overhaul, better known as the Marian reforms (circa 107 BC). Alluding to a far more influential course of action than the previous centuries of military reorganizations, these reforms resulted in the military inclusion of the capite censi, the landless Romans who were now assessed in the census and counted as potential recruits that could bolster the army.

Consequently, the state was responsible for providing the arms and equipment to these previously disfranchised masses, thus allowing many of the poorer men to be employed as professional soldiers of the burgeoning Roman realm.

The reforms also focused on the formation of a standing army, as opposed to conscripted militias who were available seasonally within the timeframe of a year. Furthermore, the amends also touched upon the provision of retirement pensions and land grants to military men who had completed their terms of service.

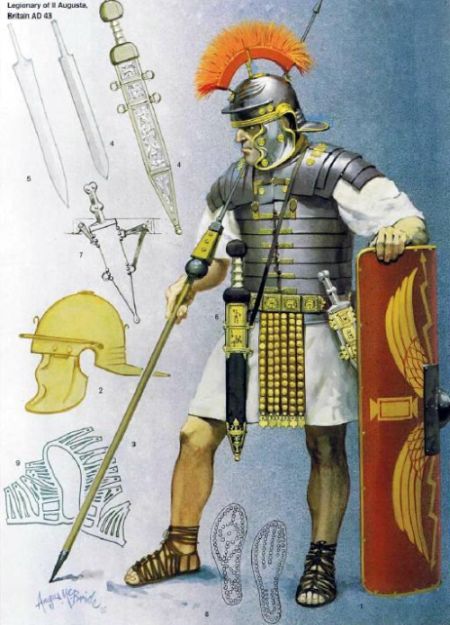

Suffice it to say, the series of reforms credibly improved the prowess of the Roman military machine, especially with the adoption of standardized equipment and training of most ranks of soldiers. Simply put, by the end of this epoch, the Roman legions were far more uniform in their appearance, while adopting systematic policies, orderly discipline, and reliable battlefield tactics.

On the flip side, the Marian reforms indirectly paved the way for the fall of the Roman Republic. The legions, by virtue of their intrinsic organization and habitual fraternity, were more loyal to their ambitious generals than the state and senate. In essence, this was the very same epoch that was witness to the ‘alarming’ triumphs of the soldiers of Julius Caesar, Pompey, and Marc Antony (as opposed to the ‘collective’ armies of Rome).

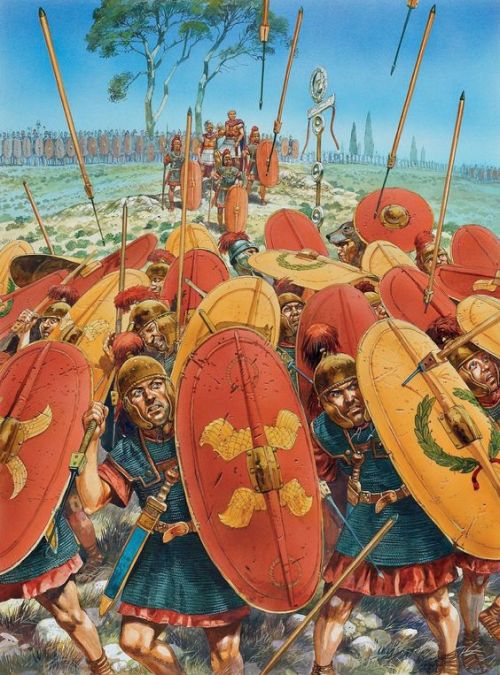

The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa 1st century AD – 2nd century AD

By 6 AD, the initial length of service for a Roman soldier (a legionary) was increased to 20 years from 16 years, and it was complemented by the praemia militare (or discharge bonus), a lump sum that was increased to 12,000 sesterces (or 3,000 denarii). And by the middle of the 1st century AD, the service was further extended to 25 years.

Now beyond official service lengths, the protocols were rarely followed in times marked by wars. This resulted in retaining the legionaries well beyond their service periods, with some men fighting under their legions for over three to four decades. Suffice it to say, such chaotic measures frequently resulted in mutinies.

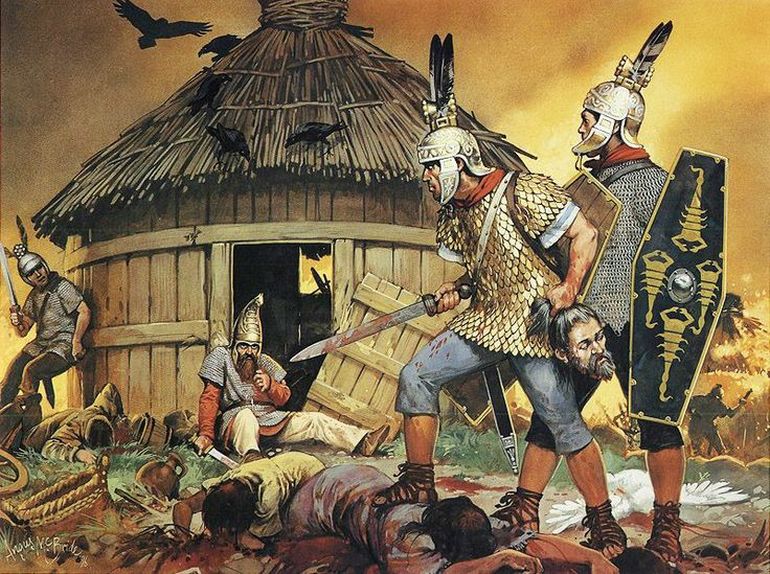

Many potential recruits were still drawn to the prospect of joining a legion because of the ‘booty factor’. In essence, many charismatic commanders touted the apparent prevalence of loot (and its ‘fair’ distribution), especially when conducting wars against richer and more powerful neighbors.

According to Cicero, this might have been the prime factor that motivated the disparate troops under Marc Antony. The popular practice also alludes to the penchant for plundering – with the soldiers tending to strip the dead as the very first act after achieving victory over their foes.

However, the life of a legionary was not all about triumphs, mutinies, and plundering. There were definitely some progressive measures put forth by the Romans when it came to bravery. For example, if the soldier was severely injured and couldn’t continue further with his military tenure, he was given a missio causaria or medical discharge that was equivalent to an honorable discharge or honesta mission.

This, in turn, equated to a societal status that was higher than ordinary civilians, which made the discharged legionary exempt from taxes and other civic duties.

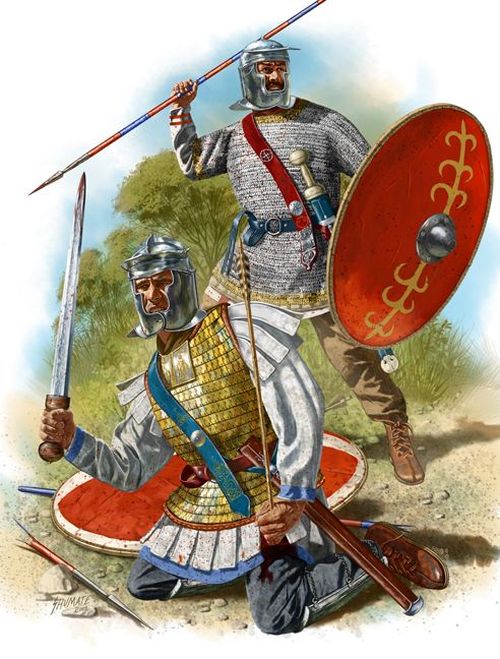

The Ancient Roman Soldier, circa 3rd century AD

While Roman legions fighting at their full capacity was a regular occurrence during the early 2nd century AD, by the middle of the 3rd century the conflicts faced by the Roman Empire (and the changing emperors) were volatile from both the geographical and logistical scope. And so it was uncommon and rather impractical for the entire legion to leave its provincial base to fight a ‘distant’ war on the shifting frontiers of the 3rd century AD.

As a solution, the Roman military commanders sanctioned the use of vexillationes – detachments from individual legions that could be easily transferred without compromising the core strength of a legion (which was needed for fortifying and policing its ‘native’ province).

These mobile combat ‘divisions’, comprising one or two cohorts, were usually tasked with handling the smaller enemy forces while being also used for garrisoning duties by strategic points like roads, bridges, and forts. And on rare occasions when the Romans were faced with a large number of opposing troops, many of these different vexillationes were combined to form a bigger field army.

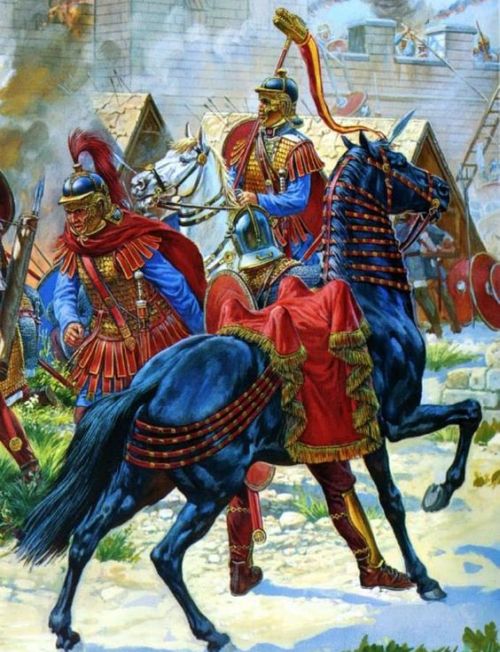

Moreover, the importance of detachments was not only limited to the combat-duty-bound vexillationes. Emperor Gallienus (who ruled alone from 260 to 268 AD) created his own mobile field army consisting of special detachments from the praetorians, legio II Parthica, and other guard units.

Hailed as the comitatus (retinue), this central reserve force functioned under the emperor’s direct command, thus hinting at the insecurities faced by the Roman rulers and elites during the ‘Crisis of the Third Century’. Interestingly enough, many of the ‘extra’ equites (cavalry) that were assigned to each conventional legion, were also inducted as the elite promoti cavalry in the already opulent (and the militarily capable) scope of the comitatus.

Timelapse Showcases The Evolution of a Roman Soldier from circa 9th century BC to 6th century AD

A time-lapse video from YouTuber foojer.

In the creator’s own words –

The evolution of the Roman heavy infantryman from the dawn of Rome right down to the coming of the Arabs. I’ve deliberately (and to save time) not included light infantry and officers. And while I’ve tried to keep the gear as authentic as I could, my focus was style rather than accuracy.

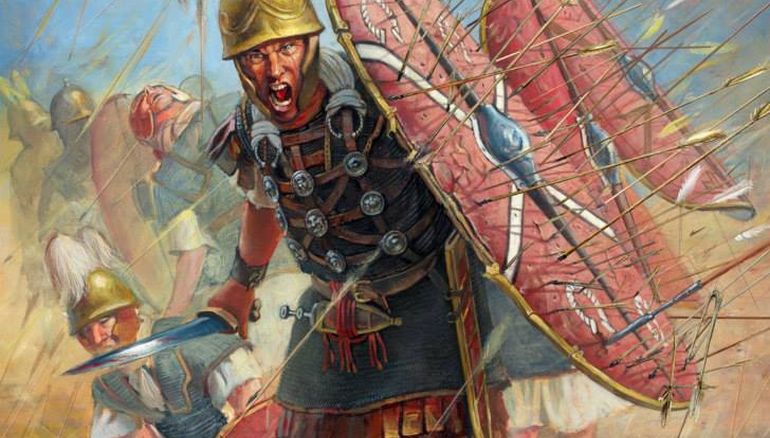

Featured Image Credit: Radu Oltean

Sources: Britannica / UNRV / Livius / MilitaryHistoryNow / Classics.UPenn / MIT.edu / V-Roma

Book References: The Roman Army: The Greatest War Machine of the Ancient World (Editor Chris McNab) / Roman Legionary 58 BC-AD 69 (By Ross Cowan) / The Roman Army from Caesar to Trajan (By Michael Simkins) / Arms and Armour of the Imperial Roman Soldier: From Marius to Commodus, 112 BC-AD 192 (By Raffaele D’Amato)

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "Remarkable Visual Reconstruction of the Ancient Roman Soldier from 8th Century BC to 3rd Century AD"