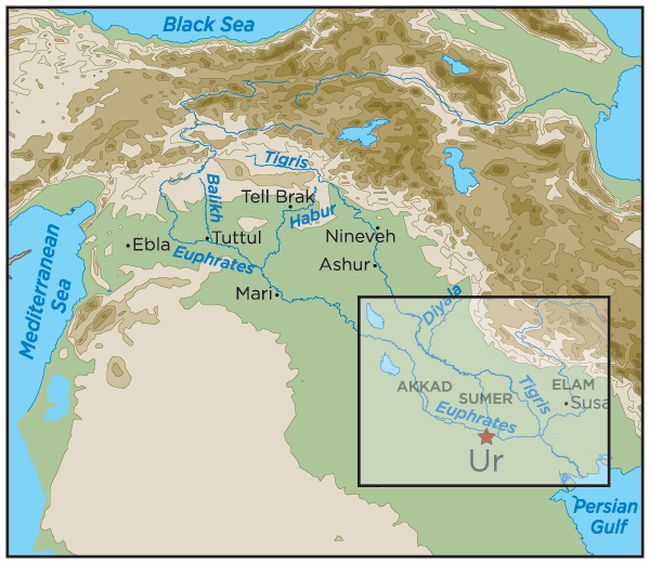

Like many great cities of history, Ur started out as a lowly village in the Ubaid Period of Mesopotamia, close to circa 4th millennium BC. However by virtue of its ‘convenient’ location by the Persian Gulf, nearby to the point where the great rivers Tigris and Euphrates met, the settlement emerged as a major trading hub of the region (by the Bronze Age), with its commercial networks connecting realms as far as India.

And while the current location of Ur is further inland due to millennia of silting of both rivers, the historical legacy of the great Mesopotamian city is still prominent, as can be gathered from the impressive (half-restored) remnants of the Ziggurat of Ur which housed the shrine of Nanna.

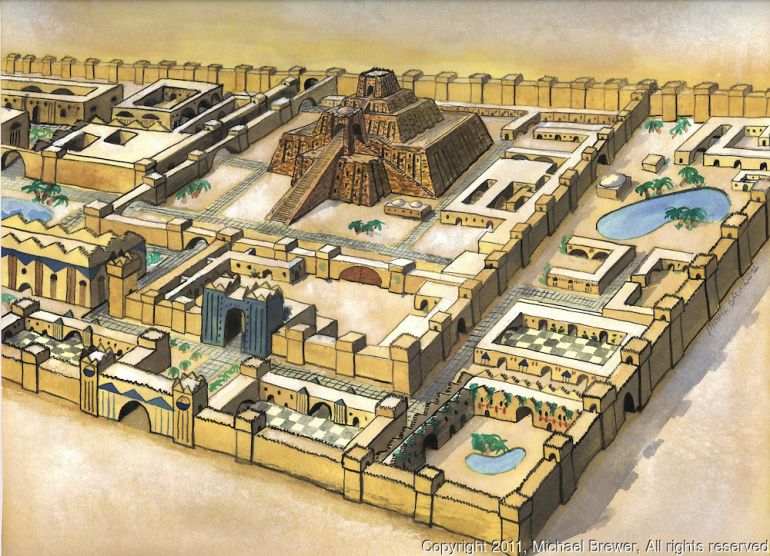

Reconstruction of Ur

The first animation/image slide presents the grandiosely conceived scope of the Ziggurat of Ur, a magnificent structure that dominated the cityscape of the flourishing settlement. This was complemented by the locational aspect of the city itself, with its formidable walls also caressing the bends of the Euphrates.

The Emulation of God-Kings

Now coming to the historical side of affairs, circa 2334 BC, the Akkadians carved up the first known all-Mesopotamian empire, thereby momentously uniting the speakers of both Sumerian and Akkadian. In fact, by the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, the Akkadians managed to create a culturally syncretic scope (that encompassed a melting pot of different ethnicity and city-states).

This ultimately paved the way for the emergence of Akkadian as the lingua franca of Mesopotamia for many centuries to come. However, beyond just cultural affiliations with the advanced Sumerians, the Akkadians also adopted (and loaned) many of the military systems and doctrines of their Mesopotamian brethren.

The two-way influence surely rubbed on the Third Dynasty of Ur (circa 2047-1750 BC), whose Sumerian kings openly emulated the heroic feats of renowned Akkadian rulers like Sargon the Great and Naram-Sin. And while many of these endeavors were clearly propagandist in nature, some translated into magnificent projects, like the aforementioned Ziggurat of Ur.

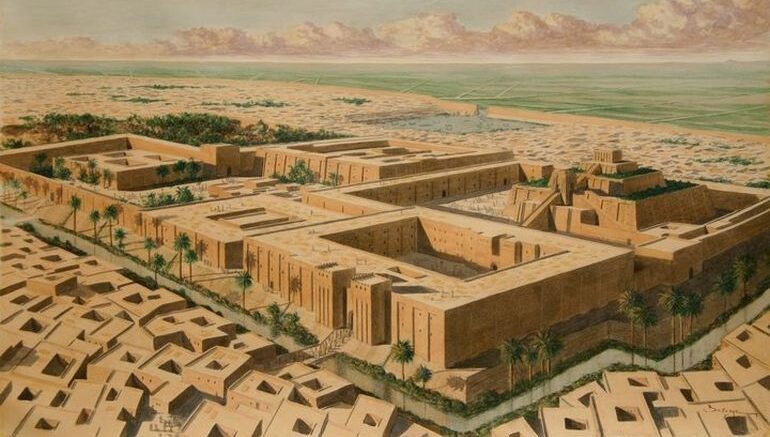

Possibly constructed under the orders of King Ur-Nammu, the step-pyramidal structure is estimated to have encompassed an area of 64 m (210 ft) in length x 45 m (148 ft) in width while rising to a height of around 100 ft. The building was completed during the reign of Ur-Nammu’s son Shulgi, who promptly proclaimed himself as the divine ruler of the proximate lands.

The Renaissance

Beyond just monumental structures, the Third Dynasty of Ur in many ways epitomized the apical stage of the Bronze Age realm of Ur. For example, as opposed to our popular notions denoting the Code of Hammurabi as the oldest set of codified laws, the actual honor possibly belongs to the Code of Ur-Nammu, which was inscribed circa 2100 – 2050 BC.

His son Shulgi took a step further by reforming the emergent kingdom into a highly centralized bureaucratic state. His amendments were complemented by personal resolve, so much so that a particular incident alludes to how the king covered (or ran) 100 miles (160.9 km) between Nippur and Ur and back again, in one day, in order to attend religious festivals in both cities.

During all of these far-flung administrative changes, the capital city of Ur itself became the bastion of culture and learning in southern Mesopotamia. The epoch coincided with the rise of trade and efficient urban management, along with the encouragement of artistic and scientific pursuits.

In that regard, it can be surmised from archaeological pieces of evidence that the residents of Ur possibly enjoyed better standards of living than many of the urban dwellers of contemporary Mesopotamian cities. The cultural prominence also accompanied the military power of Ur, the latter scope being epitomized by a massive defensive wall system that possibly stretched over 155 miles.

The royal scale of the city of Ur is aptly captured by the following animation concocted by the resourceful folks over at Zero One Animation –

The Biblical Connection?

Like many renowned cities in the intertwining narrative of history, Ur declined in importance with the rise of Hammurabi’s Babylon, which was then followed by the interlude of the Hittites, Kassites, and Assyrians. And while during this millennium, the settlement was still ‘honored’ as a center of learning, its status as a royal capital was eroded by successive waves of more dominant powers in other parts of Mesopotamia.

Ur’s proverbial ‘last hurrah’ came in the form of a spurt of new construction projects, undertaken on the orders of Nebuchadnezzar II of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. And by circa early 5th century BC, while the city was partially inhabited as a part of the Achaemenid Empire, it fell into an unrecoverable slump within a space of few decades – with the Persian Gulf receding far back from the river ports of the settlement.

Now interestingly enough, in Biblical sources, Ur may have been mentioned as being the birthplace of the patriarch Abraham, with the Book of Genesis containing the name Ur Kasdim (roughly translated to Ur of the Chaldees). Now if we take the route of history, the Chaldeans, a Semitic-speaking group of people who emerged in Mesopotamia circa the early 9th century BC, were the rulers of Ur only in the late 7th century BC (possibly).

However, most theories put forth by early 20th-century historians relate to how such patriarchs (and matriarchs) were possibly based on composite personalities from the 2nd millennium BC, thus corresponding to the Bronze Age. To that end, some scholars suggest that the Book of Genesis may have confused Ur and Ura, with the latter being a Bronze Age city near Harran, northern Mesopotamia. Other theories advocate that the confusion may have occurred from the names of cities like Urkesh, Urartu, and Urfa.

On the other hand, the great city of Ur itself may have gradually fallen into disarray due to the constant trickles of migration of its population to the other parts of Mesopotamia and Canaan. Once again reverting to the latter, the Book of Genesis clearly mentions how Abraham made his way to Canaan from his original homeland.

Now a few late 20th-century scholars (including Thomas L. Thompson and John Van Seters) have presented their hypotheses regarding how many of the Biblical texts reflect the social conditions prevalent in the 1st millennium BC, corresponding to the Iron Age. Simply put, Abraham (or at least his historical counterpart) may have been born in the Iron Age, and his settling in the land of Canaan possibly reflected the migratory pattern of many Ur emigrants.

In any case, the last video by Pier Manuel Scarpato also showcases the reconstruction of the Great Ziggurat of Ur. As the YouTuber explained –

The Great Ziggurat, which is today located in the Dhi Qar Province in southern Iraq is a massive step pyramid construction measuring 64 meters (210 ft) in length, 46 meters (151 ft) in width, and 30 meters (98 ft) in height. This height, however, is just speculation, as only the bottom of the structure survives today and even this has been heavily renovated.

Article Sources: Ancient History Encylopedia / Britannica

Be the first to comment on "Ur: Reconstruction of the Remarkably Rich Ancient Sumerian City"