Pirates and piracy have existed since the dawn of sailing. For example, ancient Greek ships were plagued by the Mamertines of Sicily, while late medieval European vessels faced the scourge of the Barbary pirates of North Africa. However, propelled by our popular culture, the very term ‘pirates’ brings forth reveries (to many of us) of the rambunctious 17th-18th-century Caribbean sailors and seamen who seemingly led their lives guided by the ‘pillars’ of adventure and freedom.

But as is often the case in history, there was more to these pirates than what their boisterously spirited personas suggest. So without further ado, let us take a gander at the fascinating history of the 17th-18th-century Caribbean Pirates.

Contents

- Beyond the ‘Glamor’ of Swashbuckling

- Privateers, Buccaneers, and Pirates

- The “Golden Age” of Piracy

- What Drove Sailors to Piracy?

- Were There Black Pirates?

- The Pirate ‘Costume’

- The Maneuver and Ruses of Pirates

- The Gun Barrage

- Boarding Actions and Cutlasses

- The Proverbial Plunder

- Honorable Mention – The Pirate Havens

Beyond the ‘Glamor’ of Swashbuckling

Historian Angus Konstam has this to say about the historical nature of pirates (in the book Pirates 1660 – 1730) –

Instead of a life of romantic glamor, with crews led by aristocratic swashbuckling heroes, the average pirate was a doomed man, lacking the education, abilities, and pragmatism to escape his inevitable fate. A pirate’s life was usually nasty, brutish, and short.

Now while the aforementioned ‘doom and gloom’ statement might be a foil to the popular cultural depictions of the ‘swashbuckling’ pirates, we should also understand that under practical circumstances, the 17th-18th-century pirates operated like any other contemporary naval company. In that regard, our romanticized notions about them ironically also relate to their ill-kept physical state and boorish nature.

However, in reality, pirates were probably more health-conscious and medically well-supplied. For example, the wreck of the famed Queen Anne’s Revenge (commanded by the infamous Blackbeard) has revealed various medical equipment, including a urethral syringe containing mercury that was used for treating syphilis, a porringer probably used for bloodletting, a tourniquet used for mitigating loss of blood during the painful amputation sessions, and other crafting items for potions and balms.

Privateers, Buccaneers, and Pirates

Pirate as a term is often generalized to mean any renegade or non-national entities operating on the high seas. Consequently, other terms like privateers, buccaneers, and even freebooters are used as synonymous elements for this broad categorization.

However, when it comes to the history of pirates, privateers were actually somewhat different in their origins and scope of operation. To that end, a privateer entailed an individual who was under contract (known as the Letter of Marque) with a government, which allowed him to attack and plunder enemy vessels during times of conflict.

Interestingly enough, a buccaneer was a special type of privateer, derived from the French boucanier (“a curer of wild meats” or “a user of boucan” – a native grill). As can be comprehended from the etymology, these men, mostly English and French stock (originally woodsmen), hailed from the West Indies – primarily based in Port Royal and Tortuga.

They were often ‘semi-employed’ by the English to prey on Spanish vessels. As for the freebooters or the filibusters, these men were mostly French pirates who were known for using their petite flibotes (flyboats). Essentially, these categories leave out the proverbial pirate – who for the most part operated independently and indiscriminately preyed on ships from various nations.

Now, of course, the terms were also used interchangeably during the 17th-18th century, with occurrences of contracted privateers turning into full-fledged pirates for greater profitability (as was the case with Captain Kidd).

And lastly, the oft-romanticized term swashbuckler is derived from the sword-and-buckler men, better known as rodeleros (‘shield bearers’) in Spanish – and they were originally the expert infantrymen (sometimes forming Conquistador divisions) of the Spanish crown operating in the New World.

*The aforementioned boucan grill was known as barbacoa in Haitian, which ultimately gives way to the term ‘barbecue’ in English.

The “Golden Age” of Piracy

Historically, the Golden Age of Piracy (when piracy reached its proverbial peak) is perceived as a relatively short period starting from the 1650s until around 1730. This era, spanning only decades, was kickstarted by the Anglo-French buccaneers who made their forays into Spanish colonies and ships.

In the very late 17th century, piracy was (possibly) rampant in the sea-based trade routes across both the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. And finally, the last hurrah of pirates in the 1720s was brought forth by mostly ex-privateers of the Caribbean islands who were left unemployed by the conclusion of the War of the Spanish Succession.

The contracted seamen and privateers from both the English and French sides took part in the proxy war waged across the Atlantic. However, with the end of the aforementioned conflict, a considerable number of them were left disfranchised.

A parallel can be drawn to the 16th-century Spanish soldiers, many of whom were unemployed by the conclusion of the Italian Wars. Some of these soldiers formed bands and went on to become Conquistadors, driven by the riches of the New World.

Similarly, in the case of the would-be pirates, the catalyst once again harked back to riches, this time in the form of the rising seaborne trade across the Atlantic (that coincided with the end of the War of the Spanish Succession) and economic development of the colonies in the Americas.

Simply put, some of the Caribbean-based seamen, lacking any form of legal employment, took to plundering merchant ships that traveled between the ports of the region. And these early 18th-century pirates are the romanticized subjects who are often (incorrectly) depicted in movies and related media – with their own cultural overtones and even lingo.

What Drove Sailors to Piracy?

In the earlier entry, we talked about the origins of the Caribbean pirates who operated during the early 18th century. But given the short and brutal lifespan of an ordinary pirate, the question can be raised – why did many such men flock under the banners of figures like Blackbeard and Kidd?

Well for one, as we already mentioned, piracy tended to thrive when there was a dearth of employment opportunities for the seamen. However, we shouldn’t view the desperation of these sailors through the lens of modern-day sensibility.

To that end, a seaman’s life was dreadful even by contemporary standards – with grueling hard work aboard ships accompanied by uncomfortable quarters, damp surroundings, and more often than not stale food.

The dismal nature of their work situation was rather exacerbated by the exposure to various diseases ranging from scurvy, typhus to dysentery and smallpox. As historian Angus Konstam mentioned how half of the deaths in this daunting line of work were caused by diseases.

On the other hand, they had almost next to no opportunities on land, with some sailors resorting to petty thievery and even begging to make ends meet. Suffice it to say, piracy presented itself not only as a contingency but also as an outlet where such desperate men could take ‘control’ of their seemingly doomed destiny.

Simply put, in some cases, the sailors preferred to have a short but profitable career as a pirate rather than a dreary life as a lowly seaman. To that end, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the majority of the pirate recruits were enlisted from the crew of the merchant ships that were captured by pirate (or privateer) bands. In most scenarios, these sailors didn’t even have a choice but to enlist as ‘new’ pirates, while landsmen were promptly left ashore or even executed.

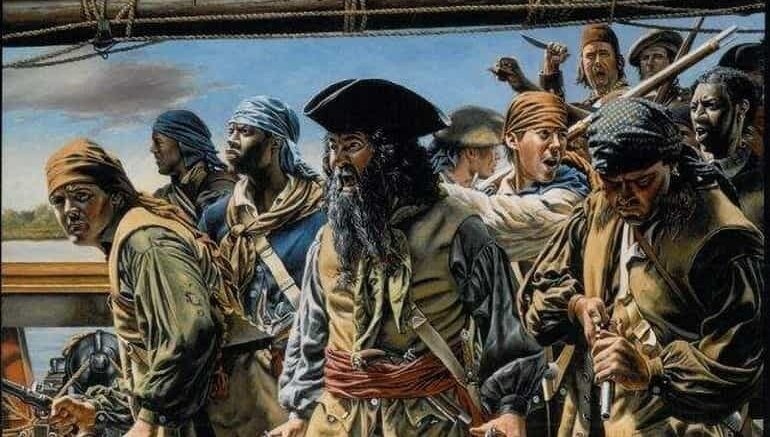

Were There Black Pirates?

Historian Angus Konstam noted how around three-quarters of the 18th-century Caribbean pirates (documented from contemporary court records) were sailors with a median age of 27. Historian David Cordingly further estimated how the majority of them were Englishmen (who mostly hailed from port cities like Bristol), followed by colonial Americans, colonial subjects of the West Indies, Scots, and Welshmen. A very small (though influential) percentage of pirates were also French, Dutch, Swedish, and even Spanish in origin.

Now the question remains – given the racial composition of many of the Caribbean islands, did Black pirates operate in the region? Well, historical records do show that a significant percentage of some (if not all) pirate ship crews were of African descent.

One pertinent example would relate to the crew of Bartholomew Roberts. After their capture by the Royal Navy, it was revealed that at least 75 men out of 263 were black.

Now objective evidence also suggests that most of these men were probably tasked with routine and rigorous duties aboard the ship (as were some white sailors). However, over time, some of the black sailors were possibly perceived as experienced crew members who played an indispensable part in many piracy endeavors.

In essence, when it comes to the later era of 18th-century pirates, there might have been a case of racial equity if not equality. The disfranchised black sailors, on their part, must have enthusiastically adopted piracy, since the very lifestyle allowed them freedom from slavery.

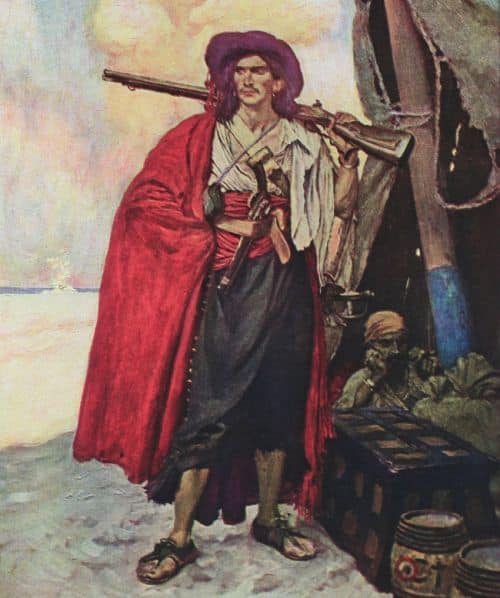

The Pirate ‘Costume’

The pirate captain of the 18th century perceived himself as a self-made, prosperous man and as such dressed as a gentleman of the era – with the attire mainly comprising breeches, a waistcoat, a long outer coat, along with a satin and leather sash.

Now, of course, his clothes and accessories depended on his plundering ability and purchasing power in makeshift auctions (of stolen goods), thus aptly reflecting his position and status among both his fellow pirates and his foes.

To that end, as could be discerned from historical records, famous captains like Bartholomew Roberts (known as Black Bart) rather flaunted their flamboyant persona with the aid of velvet, silk, damask, sarcenet, camlet, taffeta, and exotic feathers. Quite intriguingly, many a pirate possibly also dressed up in ostentatious clothing before his execution.

As for the ordinary pirates, it was a common practice among seamen to dress appropriately (and sometimes richly) when they were onshore. However, in practical circumstances onboard, they preferred tight clothes and often no footwear. As this article from Elizabethan-Era.org describes –

Pirate clothing for the ordinary seamen was often ill-fitting. Motley was a multicolored woolen fabric woven of mixed threads in 14th to 17th century England. The clothes of pirate seamen were mismatched with multi-colors – hence the expression ‘Motley Crew’. Many of the tasks performed by the pirates were extremely arduous – clothing could be easily ripped, tattered, and torn.

The pirate clothing for ordinary seamen, by necessity, was tight fitting. Loose fighting clothes would be dangerous when performing tasks like climbing the rigging. The practical fabrics used for ordinary pirate clothing included canvas, leather, wool, linen, cotton, and sheepskin.

As for their famous headgear, 17th-18th-century pirates were known to wear knotted scarves, woolen Monmouth-style caps, tricorne hats (known as ‘cocked hats’), and other anachronistic fashioned caps. Suffice it to say, beyond visual flair, the headgear was an important component of the pirate attire since it protected them from the hot Caribbean sun.

The Maneuver and Ruses of Pirates

Once again, bypassing popular culture, pirates generally targeted merchant ships by virtue of their singular goal of capturing their prize, not battling their prize. In fact, military ships of the time not only outgunned but also outnumbered pirate ships, since the former operated in squadrons while the latter tended to sail alone (or rarely with another captured vessel).

So the first step for pirates after spotting an ‘enemy’ ship, which could be done from a distance of 20 miles on a clear day, was to identify the type of vessel they would be dealing with. As we mentioned before, military ships were avoided, while merchant ships were ‘assessed’, with estimations done on the number of crew members, armaments carried by the vessel, and the speed and maneuvering capabilities of the vessel.

On occasions, a resourceful pirate captain would also try to identify and comprehend the capability of his counterpart on the merchant’s vessel. Here it should be noted while merchants’ ships were mostly not built for speed (with more emphasis on the greater volumetric capacity for cargoes), the pirates preferred their faster sloops and schooners. However, after identifying and making educated estimates about their foes, the pirates didn’t immediately set out for their targets.

Instead, they took part in various types of ruses, including raising false flags, disguising their own vessels by covering the gun ports with canvas covers, and even setting staged platforms with chicken coops and even (seemingly innocuous) female passengers. Some merchant ships, on their part, also took part in the game of cat-and-mouse by having fake gunports that could scare off potential pirates.

And once the pirates approached within their gun range, the actual flags were raised and demands were made through speaking trumpets and by firing shots in the air. The tactical situation by now transformed into a tense scene where the moves of the merchant captain would often determine the fate of the encounter.

To that end, if he decided to give his opponents a fight, the pirates would be forced to typically resort to brutality and overwhelming force (by gun barrages and boarding actions), which led to the execution of even the captured crew members of the merchant ship

On the other hand, if the merchant captain decided to yield, which was often the practical outcome – coerced by the auditory intimidation of the approaching pirates, he was asked to lower his boats and then come over to the pirate ship.

The pirates then ‘peacefully’ boarded the merchant ship, took away its cargo (or threw away the ones they couldn’t carry), seized the small boats, and finally recruited (or press-ganged) the crew members into service on their own vessels.

The Gun Barrage

The conflicts of the 17th and 18th centuries involved muskets and artillery on a grand scale, so much so that almost every European ship, irrespective of its military or mercantile purpose, was armed with guns. By extension, almost every sailor operating in the Atlantic was used to handing artillery and guns on the cruising grounds and the high seas.

As for the ship-mounted guns, the sloop and larger schooner were typically equipped with the 4-pounder (also called the Canon de 4 Gribeauval), the lightest weight cannon in the arsenal of the contemporary French field artillery.

These gun pieces weighed around 637 lbs and had a maximum range of over 1,300 yards. Larger pirate ships (like Black Bart’s Royal Fortune) obviously carried bigger guns, including the medium 8-pounder and heavy 12-pounder.

Most of these guns were complemented by the four-wheeled truck carriage that made reloading easier. As for the devastating element of the gun barrage, it was employed only when the ‘enemy’ vessel showed aggressive tendencies or failed to comply with the demands. In the Caribbean scheme of things, after verbal cues, the pirate ships unleashed their broadsides of round shots and then tried to board the opponent ship in a fairly brief maneuver.

In the ensuing chaos, they overwhelmed the opposition with their greater numbers, while also causing minimal damage to the actual prize or plunder at hand (from excessive artillery fire). In other tactical scenarios, chain-shot and grapeshots were used to damage the enemy rigging or disperse the enemy crew, with the former preventing the foe’s vessel from escaping and the latter afflicting the foe’s morale and willingness to fight.

Boarding Actions and Cutlasses

Through the shroud of smoke and mayhem of carnage, the pirates boarded the enemy ship as a tactical ploy as opposed to bouts of daredevilry. Most boarding actions were formulated by pirates so as not to damage the cargo, while at the same utilizing their numerical superiority (if available) or brute force.

In that regard, there were techniques to boarding ships, with the use of grappling hooks that were targeted at the strategic areas of the opponent’s vessel – which would gain them more coverage during melee fights while also making sure of minimal damage to the rigging (in case they wanted control of the enemy vessel).

And since we are talking about melee situations, the prowess of the pirates is embodied by the cutlass, the short broad saber that was originally developed from a machete-like weapon known as coutelas. This secondary weapon was complemented by the blunderbuss, a shotgun with a large bore – that could fire lead bullets, scrap iron, and nails.

On some occasions, pirates were also known to use the longer musket. As for the sheer brutality of these onboard fights, it is said that Edward Teach (Blackbeard) endured more than twenty wounds from smallswords (the preferred weapon of naval officers) and five gunshots before receiving his final fatal head injury.

The Proverbial Plunder

One of the most popular motifs associated with the pirates pertains to the plundered treasure chest filled with gold coins, precious stones, and jewelry items. However, when it came to actual plunders, as historian Angus Konstam noted, gold coins were pretty rare – since circulated money was in low supply in the Caribbean while the first mint in America was established only after 1776.

To that end, most of the coins (or money) were accumulated by selling off the stolen goods, as opposed to finding chance treasure troves or chest-carrying ships. Simply put, the cargoes of the targeted merchant ships were far more important to these Caribbean pirates (so that they can sell them off later or at least use them for their own purpose), and such commodities ranged from sugar, rum, wood to fur, ore, cotton, and manufactured goods of European origin.

In a few cases, the ships of slavers did carry high-value items (between the triangular slave-trading nexus comprising Europe, America, and Africa) like gold, ivory, and spices. After capturing these prized crafts, it depended on the pirate captain as to how he would treat the slaves.

In some cases, they were freed and recruited as pirate crew members or employed as workers aboard the ship. In other cases, when the allure of profit was too high, they were simply sold off to the highest bidders – with pirates taking up the role of slave traders.

Honorable Mention – The Pirate Havens

During the era of buccaneering, from the mid to late 17th century, Port Royal in Jamaica was considered the main base of privateering operations – mostly targeted at the Spanish ships in the area. However, by the turn of the century, the island government had already shifted towards the ‘legally’ profitable business of sugar, while the privateers were left disfranchised by the conclusion of the government-perpetrated wars.

By this period, the now privateer-turned-pirates gradually shifted their base of operations towards the Bahamas, namely at New Providence, the nominal capital of the islands that occupied a strategic position between America and the Caribbean. In fact, in the first decade of the 18th century, the pirates tended to operate under the implicit patronage of the local government who were paid timely bribes.

Consequently, a significant portion of the region’s trade depended on the effectiveness of piracy – which led to a pseudo-confederacy of various piratical elements dominating the water for years (if not decades). However, as expected, the dubious ‘arrangement’ was soon derailed when the Royal Navy directly intervened in the matter.

Similarly, pirates (like Blackbeard) were also known to operate and maintain relatively safe havens in the Carolinas, under the short-lived ‘protection’ of the local governments. Interestingly enough, the end of the privateering era also forced some of the buccaneers to shift to Madagascar and ply their trade on the profitable routes of the Indian Ocean.

They were later joined by the various pirate factions that had been displaced from their base in New Providence. But once again, a bolstered Royal Navy put an end to many such piratical activities in the area, which forced the remaining pirates to permanently settle on the island as civilians.

Book References: Pirates 1660 – 1730 (By Angus Konstam) / A General History of the Pyrates (By Daniel Defoe)

Featured Image Source: Tampa Bay Online

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "The Short History of the Caribbean Pirates: Freedom and Slavery"