While popular history tends to bring forth the notion of Alexander the Great as a military genius (and rightly so), his generalship was not only mirrored by his individual brilliance but also by the impressive efforts of his army. To that end, in many ways, the destiny and legacy of Alexander were rather forged by the military prowess and organizational capacity of his commanded Macedonians. So, without further ado, let us take a deep dive into the mighty ancient Macedonian army of Alexander the Great.

Contents

- Dangers Forged the Macedonian Army of Philip

- The Personal Companions and Royal Pages

- Somatophylakes or Bodyguards

- The Hetairoi or Companion Cavalry

- The Pezhetairoi or Foot Companions

- The Hypaspists or Shield Bearers

- The ‘Multinational’ Force of Alexander the Great

- The Thessalians and Thracians

- The Allied Greeks

- The Mercenaries and Other Troops

- Honorable Mention – The March

- Visual Reconstruction of the Macedonian Phalanx

Dangers Forged the Macedonian Army of Philip

When Philip II of Macedon (or Phílippos II ho Makedon – Alexander’s father) ascended the throne of Macedon in 359 BC, his realm was beset on the northern side by the ravaging Illyrians and precariously poised on the southern borders with the opportunistic Greeks. To make matters worse, the Macedonian army was all but vanquished – with their earlier king and many of the hetairoi (king’s companions) meeting their gruesome deaths in a battle against the invading northern tribes.

But as the saying goes – “necessity is the mother of all inventions”; Philp went on to initiate a military reform of sorts that focused on training and equipping the infantry levies of Macedon, many of whom came from semi-nomadic shepherding backgrounds (as opposed to the Greek farmer/hoplite tied to his land).

Partly inspired by the great general Epaminondas and his Theban army, and also influenced by the contemporary Athenian general Iphicrates, Philip adopted the nascent ideas of the Macedonian phalanx – wherein the infantrymen, in their deep formations, were armed with heavy, lengthy spears but armored in light attires.

This ‘anvil’ of solid bodies of infantry was complemented by the ‘hammer’ of elite cavalrymen – Philip’s new ‘companions’ comprising various Greek nobles settled on the fiefs taken away from previous enemies. As a matter of fact, Philip invited military families from across Greek states to politically counteract the native-born Macedonian nobility.

These corps of mostly loyal mounted warriors were presented with heavy cuirasses and Phrygian helmets, and they acted as a hard-hitting yet mobile force on the battlefield. Consequently, by the time of his death, Philip’s army had successfully extended the Macedonian frontier into southern Illyria, while also establishing dominance over the Paeonians, Thracians, Thessalians, and even Greek city-states like Athens and Thebes.

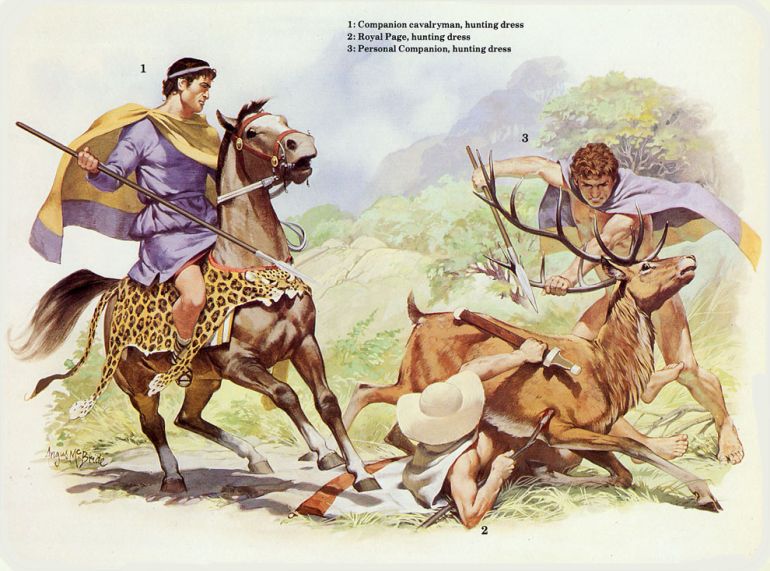

The Personal Companions and Royal Pages

Now it should be noted that hetairoi as a term is pretty vague, and it could denote both the aforementioned ‘companion’ cavalry and the king’s own personal companions. The latter group possibly included the courtiers of ancient Macedon, who traveled with the basileus (king) and convened with him in the royal tent.

Ancient sources also mention the term philoi (friends), which could have probably denoted the personal companions who held the highest positions in the hierarchy of the court. Interestingly enough, Alexander also preferred his dedicated ‘department’ of chaplains. These men, often accompanying the marching army, had the important duty of convincing the soldiery of favorable battle omens by a mix of showmanship and augury.

Beyond the hierarchy of personal companions, Alexander the Great also approved of more centralized control over the nobles of Macedonian society. A practical solution came forth in the form of the Royal Pages (Basilikoi Paides).

This group comprised the sons of nobles who were incorporated into the aristocratic court, albeit as servants of the kings. Fulfilling a role similar to the medieval squires, these teenage males were basically taken up as hostages who would serve as ‘guarantees’ of their parent’s loyalties.

Beneath this political veneer, the Royal Pages also performed a practical function. As the noble youth of the burgeoning realm, they were indoctrinated and inducted into the loyalty-based cult of the king. At the same time, they were trained within the workings of the royal machinery, ranging from menial tasks (including pouring the king’s bath), and administrative jobs to even martial requirements.

And on ‘completion’ of the term, many of these young men (on entering adulthood) were drafted as officers of Alexander’s army or as members of the elite corps of Companion Cavalry – thus alluding to a cyclic order of military support from the noble families.

Somatophylakes or Bodyguards

Somatophylakes or Bodyguards probably comprised a separate unit within the ancient army of Alexander. One of the clues comes from the position of the Royal Bodyguard (Somatophylax Basilikos) – which was considered the senior-most rank in the army.

Originally, there were seven such high-ranking officers, with the number symbolizing their first-hand duties that entailed guarding the massive royal tent. To that end, it is known that Alexander’s closest friend Hephiastion commanded the Bodyguards at the famous Battle of Gaugamela.

In essence, it can be hypothesized that the Somatophylakes took an active part in actual military encounters, though their numbers were probably very low – in the range of just 200 men. On occasions, they possibly even functioned as the Hypaspists, the shield-bearers we will talk about later in the article. However, beyond their martial capacity, it is their origins that have perplexed historians.

For example, Diodorus talked about how the king’s friends or philoi had sent around 50 of their sons to serve as bodyguards in Alexander’s army. Curtius, on the other hand, talks about how these ‘bodyguards’ performed the function of Royal Pages, which goes against the Macedonian norm that forbade noble male adults (as opposed to teenagers) from performing menial tasks.

But if we combine the two elements, we can deduce the possibility of the Somatophylakes being recruited from the Royal Pages who had shown their martial acumen (upon entering adulthood). Simply put, the Bodyguards probably was an active combat unit (manned by the elite warriors who swore to protect their Basileus) and possibly also an institution for officer training and even staff support.

The Hetairoi or Companion Cavalry

The Hetairoi or Macedonian Companion cavalry was in many ways a military extension of the political framework of ancient Macedon centered around the king himself. As we mentioned before, most members of this elite cavalry regiment were recruited from the nobles (and their sons). They possibly numbered around 1,800 men, divided into 8 squadrons (ilai), before the start of Alexander’s momentous expedition into Asia.

Among these Macedonian cavalry units, the Royal Squadron (Basilike Ile) with its double numbers held the position of honor in battles. Unsurprisingly, most of its members were usually drawn from the Personal Companions and Friends (philoi) of the Basileus himself.

Befitting the elite ‘hammer’ of Alexander’s army, the Hetairoi flaunted their uniforms, with the Royal Squadron members ostentatiously displaying purple cloaks or chlamys (dyed with Tyrian purple) with golden yellow borders – many of which were confiscated from the Persian treasury.

The Macedonian cavalryman was also presented with standard yet flexible cuirass, possibly made of small metal pieces that were reinforced with leather or covered in white linen, along with the Boeotian helmet that replaced the earlier Phyrgian model.

As for offensive weaponry, the Companions, as shock cavalry units, were equipped with the lengthy xyston spears usually made of sturdy cornel wood, and these were backed up by the secondary weapons of swords.

Interestingly enough, there may have been a conspicuous absence of shields (the mainstay of Classical Greek warfare) – when it came to cavalry maneuvering, except on rare occasions. And since we brought up defensive equipment, it is widely known that Alexander himself preferred to ditch his cuirass in favor of just his tunic, probably to enact bouts of bravado during the earlier parts of the expedition (or possibly due to the heat).

Suffice it to say, fueled by the personality cult of Alexander the Great, many of the impressionable noble youths from the elite cavalry regiments may have also tried to mimic their Macedonian king and charged into the battle – wearing just their ritzy tunics and armed with the xysta.

The Pezhetairoi or Foot Companions

Before Alexander’s army crossed the Hellespont, the mainstay of the Macedonian infantry comprised the Pezhetairoi (or Foot Companions) – men who formed up the dreaded ‘anvil’ of the Macedonian phalanx (for more details on the Macedonian phalanx, check this article).

Numbering around 9,000, these Macedonian infantrymen were divided into six battalions (taxeis) – each comprising three lochoi. And mirroring the honored units of their cavalry counterparts, the Pezhetairoi possibly had an elite taxis of their own known as the Asthetairoi, with its members (preferably) recruited from Upper Macedonia.

Now in terms of equipment, ancient writers and pictorial evidence rather paint a vague picture of the renowned foot companions. According to Polyaenus’ account of Macedonian military training, the infantrymen of the phalanx were supplied with bronze helmets (kranos) of the Phrygian variety, light shields (pelte), greaves (knemides), and their characteristic long pikes (sarissai).

So as can be gathered from this small list of items, the armor is conspicuously missing. On the other hand, Diodorus talked about standardized forms of armor being issued to Macedonian troops during the tough Indian campaign, thus suggesting how at least some of the Pezhetairoi wore cuirasses.

Moreover, instead of the heavier hoplite shield (aspis), the Macedonian phalangite shield (pelte) was smaller and lighter, which allowed the foot companion to wield his pike with two hands – as the pelte was slung across the left arm.

Interestingly enough, one of the accounts of Polyaenus anecdotally entails how Alexander himself armed the men who had previously fled the battlefield with a hemithorakion – a half armor that only covered the front part of the body so that the soldiers wouldn’t turn their backs on the enemy.

In any case, as we fleetingly mentioned, beyond the scope of their armor, it was the bristling set of pointed pikes that presented a nigh-impenetrable (albeit rigid) formation of the Macedonian phalangites. The longest of these sarissa pikes reached 18 ft during the times of the Wars of the Successors (322 – 275 BC) after Alexander’s death.

Considering the defensive attitude of his successors, it can be assumed that the Macedonian pike design was possibly somewhat shorter during Alexander’s lifetime. These lengthy spears were also known for their distinctive small iron heads that were more conducive to breaching the armor of the enemy.

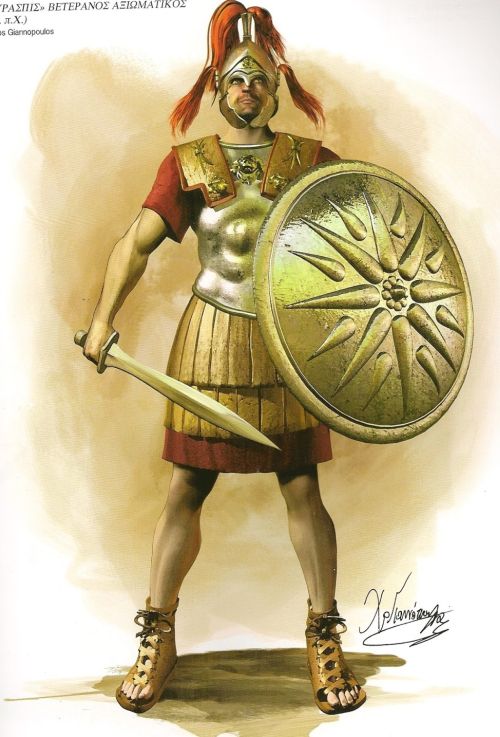

The Hypaspists or Shield Bearers

Many historians have theorized that the Hypaspistes (‘Shield Bearers’) had their origins as retainers of the Companions of the royal court (not to be confused with the Hetairoi Cavalry). While others have hypothesized that they evolved from the mainline Pezhetairoi infantry (discussed in the earlier entry).

In any case, they probably bore a higher rank than the members of the Macedonian phalanx, and such also comprised an agema (vanguard) known as the Royal Shield Bearers (Basilikoi Hypaspistes).

This unit made up of taller candidates, expressly took the position of honor on the battlefield on the right side, supported on the left by other lochoi of Hypaspistes – and together they possibly had a strength of around 3,000 men.

Now considering the relatively rigid tactics of the aforementioned Pezhetairoi, it can be surmised that the Hypaspistes probably fulfilled a flexible battlefield role that bridged the gap between the mobile cavalry and the ‘rigid’ phalanx. Judging by this requirement for agility, it can be assumed that the Hypaspist wore less armor when compared to the standard Macedonian infantryman.

To that end, Alexander may have equipped many of his Hypaspistes in a manner similar to that of Greek hoplites, thus suggesting the usage of Phrygian helmets, lighter tunics, and shorter spears (dory). To that end, some of these veteran soldiers might have also carried the traditional Greek hoplite shield (aspis).

At the same time, the Shield Bearers formed the crack units of the army. Thus they proved their worth in many a siege battle, by taking part in the frontal assaults conducted within cramped quarters. In essence, it is fair to assume that the Hypaspistes were better trained and drilled than most contemporary infantry units, while their (required) agility kept them at the peak of their physical conditions.

Given their esteemed martial value, many of the veteran Hypaspistes possibly also formed the renowned Argyraspides – the ‘Silver Shields’. These veteran warriors later also took part in the Wars of the Successors (Diadochi) after Alexander’s death.

The ‘Multinational’ Force of Alexander the Great

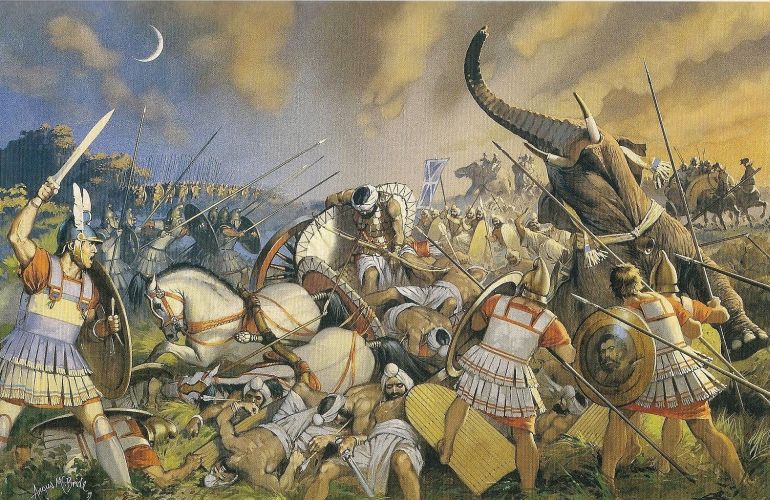

Our popular notions about the ancient army commanded by Alexander the Great in his renowned campaigns mostly hark back to a homogenous Greek-speaking force comprising of the ‘anvil’ phalanx and the ‘hammer’ cavalry. However, in truth, the ‘new Macedonian army’ was composed of soldiers who came from different backgrounds and nationalities.

For starters, the Macedonians themselves, who formed up the ‘Royal Army’, were bolstered by their vassals, including the Triballians, Agrarians, Odrysians, and even Illyrians – their former enemies.

Alexander was also the de-facto head (archon) of the Thessalian army and the commander of the League of Corinth which gave him the power to levy military support from the Greeks. Additionally, Macedonian kings hired mercenaries, most of whom hailed from the southern Greek realms and the neighboring Balkans.

In fact, contrary to our modern concept of political correctness, there was rampant racism and preconceived ideas directed against other groups within the army. For example, the southern Greeks perceived their northern Macedonian brethren as being uncouth and even semi-civilized. The Macedonians, on the other hand, regarded their southern neighbors as being effete and soft.

And both these essentially Greek groups identified the Thracians as barbarians, on account of their foreign language and boisterous tendencies. However, in spite of these cultural differences, the ‘hotch-potch’ of Alexander’s force was admirably successful in conducting long-lasting campaigns while enduring logistical obstacles – feats that were only matched by Hannibal and his army of ‘multinationals’ more than 80 years later.

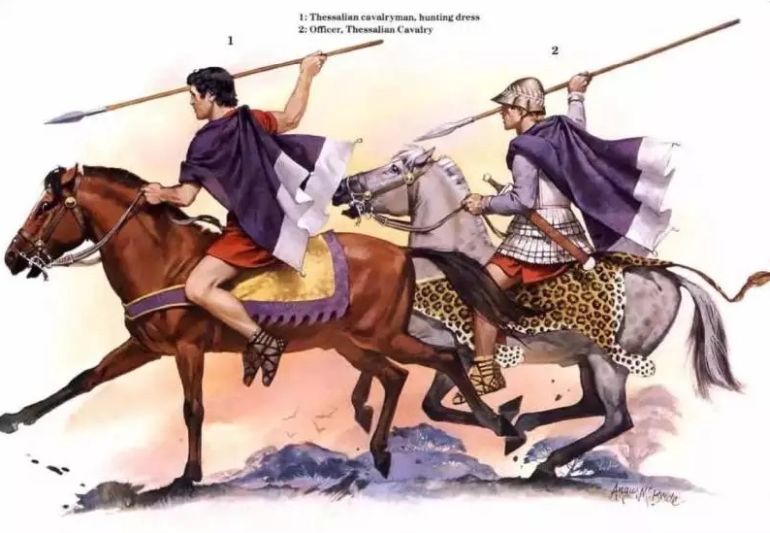

The Thessalians and Thracians

With all the talk about the elite Companion Cavalry, it may come as a surprise that it was actually the Thessalian cavalry contingents who were considered the finest horsemen in Alexander’s army (and possibly even the whole Greek world). Many of these valued cavalrymen were borne by the equestrian culture prevalent in the Thessalian noble class – and as such their regiments possibly mirrored the structure of the much-heralded Hetairoi.

To that end, ancient sources talked about how 1,800 Thessalian horsemen took part in Alexander’s Asia expedition, a number matched by the Companion Cavalry forces. Expectedly, they played crucial roles in warding off the attack of Persian cavalry forces at both Issus (333 BC) and Gaugamela (331 BC) respectively.

It can be assumed that the Thessalian cavalry was similarly divided into eight squadrons (ilai), with the agema (vanguard) pertaining to the Pharsalian squadron – the Thessalian counterpart to the Royal Squadron (Basilike Ile) of the Hetairoi.

As for their attire, the Thessalian horsemen probably wore their distinctive dark purple cloaks with white borders, while being armored in the similar white-hued cuirasses preferred by the Companions.

The Thracians, on the other hand, were perceived as an unruly bunch by their Greek neighbors. Nevertheless, they were renowned for their effective light cavalry forces. The Prodromoi (scouts) was one such Thracian unit that was attached to the Royal Army (comprising only Macedonians), and they possibly consisted of four squadrons.

And even beyond the official designations of Prodromoi cavalry, the now Macedonian empire was often reliant on Thracian cavalry – as these highly mobile auxiliary forces were suited to essential scouting and raiding activities inside enemy territories.

In terms of panoply, the Prodromoi wore light tunics (without armor), possibly complemented by rose-colored cloaks (and the panther-skin shabraque for officers). They were also known to carry the longer sarissai instead of the sturdier xysta preferred by the heavy cavalry regiments.

The Allied Greeks

Delving into the units of the infantrymen, earlier we talked about how around 9,000 Pezhetairoi (or Foot Companions), the main phalanx force of the Macedonian army, were assembled for Alexander’s incredible military expedition against the Persian Empire. They were accompanied by 3,000 Hypaspistes (or Shield Bearers) and around 7,000 allied Greeks.

Pertaining to the latter, it has been hypothesized that some of these allied Greek armies (along with mercenaries) were possibly relegated to garrison duties after crossing the Hellespont.

Nevertheless, it can also be assumed that the Greeks of the League of Corinth were pretty well drilled, mainly because of their own set of reforms initiated after the disastrous defeat at Chaeronea (ironically handed by the Macedonian armies of Philip II).

One significant outcome of these reforms related to the phasing out of the typical ‘militia’ Greek hoplites in favor of the epilektoi (picked troops). Unlike hoplites, however, these epilektoi, almost akin to mercenary Greek heavy infantry, had to be paid on a regular basis – a system that often severely affected the fiscal condition of many individual city-states.

And in terms of armor, many of these infantrymen possibly “re-adopted” the heavier muscled cuirass and the ubiquitous Phrygian helmet. It should also be noted that some Greek city-states offered their military support in the form of cavalry forces.

Diodorus talked about at least 600 Greek horsemen crossing the Hellespont with the main expeditionary force, and they were possibly reinforced by other detachments later in the campaign.

The Mercenaries and Other Troops

In addition to around 3,600 heavy cavalry forces (comprising the Hetairoi and Thessalians), complemented by around 1,400 light cavalry troopers (comprising Thracians, Greeks, and other auxiliaries), the Macedonian army of Alexander also inducted mercenary horsemen.

In fact, judging by the aforementioned figures, Alexander desperately needed more light cavalry, not just to balance his forces, but also for scouting activities in deep enemy territories that often played their part in strategic decision-making.

These mercenaries, comprising Persian light cavalry and even Iranian horse archers, were possibly arranged in two squadrons. These units fought under the umbrella of ‘Foreign Mercenary Cavalry’ – and as such proved their worth against mighty equestrian opponents like the Bactrians and Scythians at Gaugamela.

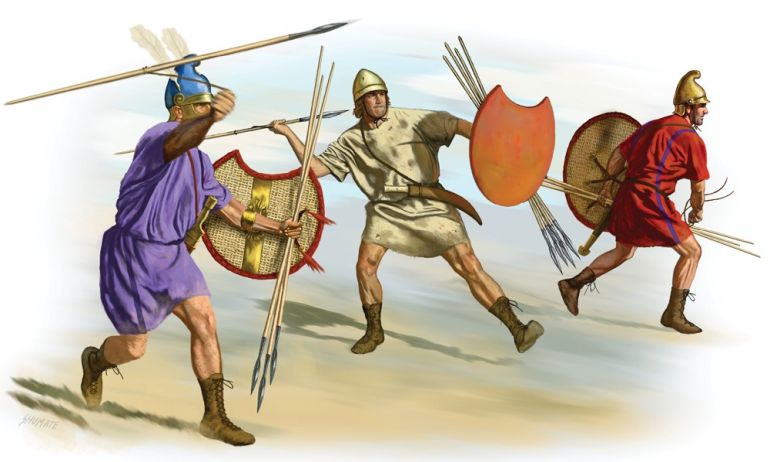

And beyond the scope of standard infantrymen and cavalry, the Macedonian army presumably also had its fair share of light skirmishers (psiloi), who fought in front of the packed phalanx formations – though not much is known about their numbers.

What we do know, however, is that Alexander specifically recruited a company of the renowned Cretan archers (toxotai). They were known for carrying their bronze pelte (light shield) that also aided them in close-combat scenarios.

Interestingly enough, other than archers, the light troops that played their instrumental role in many a military encounter, pertained to the peltasts and javelinmen (akontistai). The most famous of these skirmish infantry arguably related to the elite light crack troops of Agrianians, who numbered around 1,000 and carried both short and long javelins.

And while grouped under the general term of ‘Thracians’, Diodorus also talked about 7,000 multinational light troops accompanying the main Macedonian army at Hellespont – and they possibly comprised akontistai contingents of the Triballians, Odrysians, and Illyrians.

Honorable Mention – The March

The basic tactical unit in the Macedonian army was known as the dekas, which contrary to its allusion to the number 10, actually consisted of sixteen men – the equivalent of a single file in a square formation of the phalanx (comprising 256 men).

Each dekas was officially allowed to have only one servant, known as ektaktoi, and his job entailed looking after the precious baggage (containing the main tent and other accessories) of the combatants, usually carried by mules, horses, and later even camels.

Now in spite of such frugal means and lack of actual pay (that was usually replaced by the plunder taken from enemy settlements), the infantrymen who had joined Alexander in 336 BC and then embarked on his Asia-bound campaign, had traveled more than 20,870 miles (or 33,400 km) by the time Alexander breathed his last in Babylon (in 323 BC) – according to a calculation made by historian Theodore Ayrault Dodge.

So, on average, each of these men had covered an impressive 1,605 miles (or 2,570 km) per year! And, when translated into geographical terms, many of the Macedonian veterans could have claimed to cross a multitude of rivers including the Nile (in Egypt), Euphrates and Tigris (in Iraq), Oxus (in Tajikistan), Syr-Darya (in Uzbekistan), and the Indus (in India).

Visual Reconstruction of the Macedonian Phalanx

YouTuber Historia Civilis has concocted a nifty animation that aptly presents the famed ‘hammer-and-anvil’ tactic of the mighty army during Alexander’s time.

Sources: WeaponsandWarfare / Twilight of the Polis and Conclusion – Lecture By YaleCourses

Book References: Alexander the Great at War (Edited by Ruth Sheppard) / Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age ( By Peter Green) / The Army of Alexander the Great (By Nick Secunda)

Be the first to comment on "The Mighty Ancient Macedonian Army of Alexander"