Introduction

The ancient Greek helmet is a familiar motif when it comes to popular cultural depictions of Greek history and mythology. However, quite unsurprisingly, many of such portrayals often tend to favor stylized versions (or specific types) of the helmets, with one pertinent example relating to the overuse of Corinthian helmets as movie props.

But as is the nature of history, it was practicality and effectiveness that often trumped the style factor. To that end, let us take a gander at the history and design of ten ancient Greek helmets that were developed over a passage of a millennium – from the Bronze Age (16th century BC) to the Late Classical Period (4th century BC).

Contents

- Introduction

- Boar’s Tusk Helmet (origins – circa 16th century BC)

- Kegelhelm (origins – possibly circa 10th century BC)

- Corinthian Helmet (origins – circa 8th century BC)

- Illyrian Helmet (origins – circa 7th century BC)

- Chalcidian Helmet (origins – circa 6th century BC)

- Pilos Helmet (origins – circa 6th century BC)

- Attic Helmet (origins – circa 5th century BC)

- Phrygian Helmet (origins – circa 5th century BC)

- Boeotian Helmet (origins – circa 4th century BC)

- Konos Helmet (origins – circa late 4th century BC)

Boar’s Tusk Helmet (origins – circa 16th century BC)

The early Mycenaean (Bronze Age Greek) spearmen probably employed massed ‘shoulder to shoulder’ formations, further complemented by their sturdy shields and weapons, as opposed to hefty armor systems (that were mostly eschewed in favor of light clothing). But while the shield could cover most parts of the body, the head was still exposed to blows in a melee situation. This is where an Aegean invention came to the fore, in the form of the special boar tusk helmet.

Giving a literal meaning to their name, these helmets were actually reinforced with the sturdy tusks of boars – which were primarily shaped in smaller pieces, bored with holes, and then expertly stitched on a conical leather framework. Special care was taken to alternate the curves of these shaped tusks in the concurrent rows, while the crown was embellished with a plume or a knob.

Some of the specimens possibly even had cheek guards (that extended downwards), thus accounting for a formidable head defense. Interestingly enough, Homer makes a full description of such boar tusk helmet types and their prevalence in the Trojan War.

He also goes on to explain how the ‘Greeks’ (or Mycenaeans) acquired these tusks due to their penchant for hunting. In any case, from the historical perspective, like many things Mycenaean, such helmet types were possibly inspired by the advanced Bronze Age Minoans.

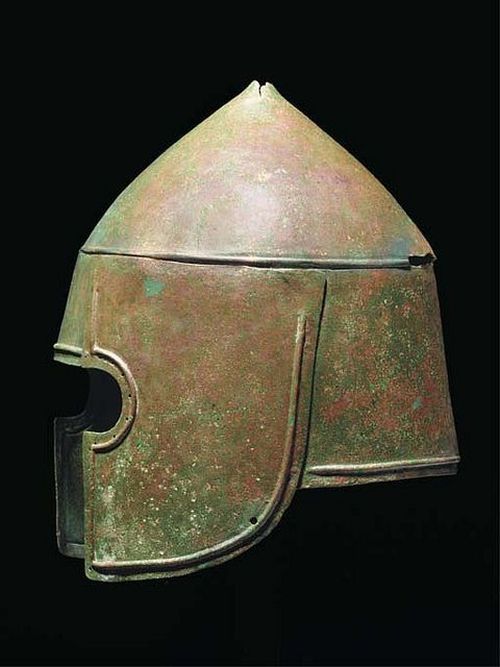

Kegelhelm (origins – possibly circa 10th century BC)

Although not much is known about the usage pattern of the Kegehelm, historians, and archaeologists have hypothesized that this conical contraption was probably one of the oldest Iron Age helmets used in mainland Greece. Exhibiting its distinct shape (kegel meaning ‘cone’ in German), the helmet was basically constructed from five pieces, including a conical cap (pictured above), cheek pieces, and even a forehead guard.

The form factor of the Kegelhelm is directly known from three 8th-century tombs in Argos that contained remnants of the helmets. Interestingly enough, archaeologists noted how the crest of one of these Iron Age specimens resembled the helmets used in contemporary Assyria (corresponding to the Neo Assyrian Empire).

However, beyond Mesopotamian influence, scholars have also conjectured that the Kegelhelm was possibly a Greek adoption of similar helmet types used by the earlier Minoans. In any case, the Kegelhelm was soon discontinued in favor of the renowned Corinthian Helmet, because of its inherent weakness in design relating to the joins by which the aforementioned pieces were attached to the main conical cap.

Corinthian Helmet (origins – circa 8th century BC)

Popular cultural depictions of ancient Greek hoplites tend to portray them as wearing the seemingly ornate Corinthian helmet. One of the reasons for this actually stems directly from history, with many Greek sculptural specimens also showcasing the Corinthian helmet as the preferred helms of their heroes and commanders.

In fact, during the Classical period, the Corinthian helmet with its stylized design romanticized the warriors and past glories of the early Archaic age (circa 9th century BC) – the epoch during which the Greeks made impressive progress in the fields of politics, architecture, military, and trade-based economics.

Coming to its design elements, the Corinthian helmet was usually made from bronze or brass, with the early variants possibly crafted from a single sheet (while more practical variants were made from two welded pieces). As for the form factor, the typical Corinthian helmet provided complete protection to the wearer’s head, jaws, and nose (in some cases, overtly so) with its extensive cheek guards, nasal guard, and even collar-level protection.

With the passage of time and fueled by increased monetary means, some of the hoplites flaunted plumes made from dyed horsetails on their crests, along with intricate carvings on the helms, thereby projecting a sense of elitism (often associated with the Corinthian helmet).

However, when it came to practicality, especially during intense battle scenarios, the Corinthian helmets may have proved to be somewhat obtrusive to many of its wearers. One of the reasons might have related to how the closed nature of the design impeded the peripheral vision of the wearer, along with possible obstruction to their hearing capacity. We also know that many hoplites preferred to keep the Corinthian helmets tipped back on their heads during non-combat situations, thereby suggesting the cramped nature of the designs.

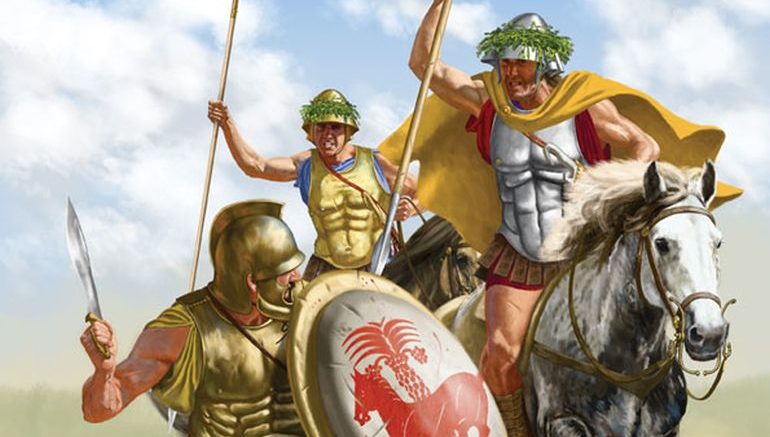

Consequently, the restrictive helmets began to fall out of favor for the practical armies of late Classical Greece (circa 4th century BC). On the other hand, some of the stylized variations were continued with further modifications, like the Italo-Corinthian helmet (pictured above) often displayed by the elites of the Roman Republic (that was worn more like a cap rather than a helmet).

Illyrian Helmet (origins – circa 7th century BC)

In contrast to the ‘enclosed’ Corinthian helmet, the Illyrian type – named so because of a significant number of archaeological finds in Illyria (the western part of Balkan), was relatively unobtrusive defensive equipment that was open on the front.

Some historians suggest that the Illyrian type was possibly an evolution of the previously mentioned Kegelhelm from the Archaic Age site at Argos. To that end, the very name might be misleading, since the hypothesis is that the Illyrian helmets were first manufactured in the Peloponnese region of Greece.

As for its design, the helmet was made of two metal pieces (usually bronze) that were joined at the crown. This joint (seam) was flanked on either side by two ridges for reinforcement, while the helmet extended with its cheek pieces and the rear neck protection.

However, as we mentioned before, the front side was open, thus allowing the wearer to maintain his visual bearing. On the other hand, the first varieties of the Illyrian helmet, made in Olympia, probably impeded the hearing of the soldiers, thereby allowing for further modifications that were made by Corinthian workshops.

Chalcidian Helmet (origins – circa 6th century BC)

With its name derived from Chalcis, on the island of Euboea (where the helmets were depicted in pottery), the Chalcidian helmet was the evolution of the more ostentatious Corinthian helmet. Preserving some of the stylized features of its heavy precursor, the lighter Chalcidian helmet was also imbued with practical design upgrades that allowed its wearer to have better hearing and relatively unimpeded vision.

Another interesting point to note is that the Chalcidian types were often made in customized batches, in accordance with the need of the wearers. This allowed for an efficient manufacturing process of modular pieces, like extended cheek guards that could be attached to the main helm through hinges.

Coming to the design scope, visually the Chalcidian helmet was a modified version of the Corinthian type, with a less-pronounced nasal guard and a relatively open form factor (like the ear openings). In a few cases, the enhanced ergonomics was often accompanied by some decorative elements, like various extensions on the top for a better visual flair. The latter suggests that the Chalcidian helmet (at least in some cases) was still the preferred helm of the elites – thus also making it a motif for ceremonial purposes.

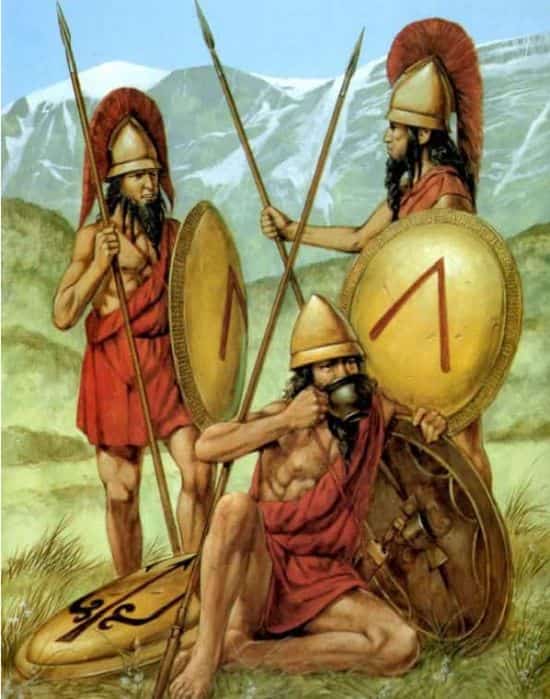

Pilos Helmet (origins – circa 6th century BC)

Simplistic, cheap, and effective – this, in a nutshell, defined the Pilos Helmet. Derived from the conical hat of the same name (which was a prevalent traveling headgear in ancient Greece, usually made of felt or leather), the Pilos helmet was made of bronze and was usually conical in shape. According to most historians, this simple helmet-type, befitting its unadorned bearing, was adopted by the Laconians (Spartans) circa the 5th century BC.

Suffice it to say, given the very shape and uncomplicated form of the Pilos helmet, the defensive equipment was easier to produce and cheaper to make (with comparatively less volume of metal required).

Furthermore, the helmet type was more suited to the Spartan mode of warfare due to its intrinsic open-faced design that allowed for better communication and battlefield awareness among the soldiers in a tight phalanx. Interestingly enough, by virtue of this very unobtrusive nature of the Pilos helmet, it was also used by lighter troops, such as the archers employed by Athens.

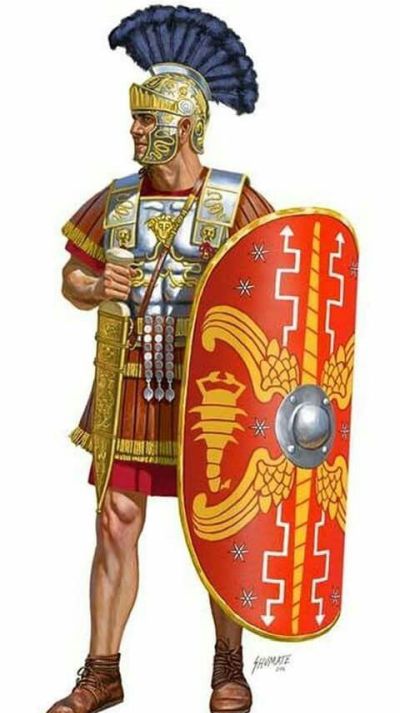

Attic Helmet (origins – circa 5th century BC)

Often perceived as an Athenian modification of the Chalcidian type, the Attic helmet bears similarities in design to its predecessor, like attachable cheek guards, but also forgoing elements like the simple nose guard. However, interestingly enough, while the helmet undoubtedly originated in the Greek mainland, its usage was relatively limited in the proximate areas, especially in comparison to the Phrygian, Corinthian, and Pilos helmets.

On the other hand, the Attic helmet was somewhat popular in Italy, and more so during the Roman era. A part of this had to do with how Romans and especially their Praetorian Guard flaunted the stylized Attic helmet variant with engravings and plumes. Unfortunately, both archaeological pieces of evidence (or lack thereof) and private relief works tend to dismiss the practicality of such Attic helmets.

This certainly alludes to the hypothesis that the Attic helmet depiction was mostly used as an artistic nod to Greek heritage in Roman circles (when it came to commemorative columns). In that regard, both ordinary Roman legionaries and the Praetorians probably wore simpler helmets (like the Montefortino-style) in actual battle scenarios, at least during the early part of the Roman Empire. This, in turn, relegates the possible use of Attic helmets in ceremonial parades.

Phrygian Helmet (origins – circa 5th century BC)

Flaunting its characteristic forward-inclining apex, which resembled the Phrygian cap (usually made of leather), the Phrygian helmet possibly originated in Classical Greece. It was widely used in regions in and around Greece and even Magna Graecia (southern Italy), including Thrace and Dacia.

In terms of design, the skull core of the equipment was made from single sheet bronze, while the conspicuous apex was made separately and then tightly riveted to the main helmet. Another element to note was a slight front projection of the skull that not only provided the user with some shade but also provided practical protection from downward-angled sword blows aimed at the head.

The Greeks, especially the Macedonians used cheek-pieces that could be attached to the main helm (much like the Chalcidian and Attic helmets). With the passage of time, such cheek-pieces became more elaborate with bridges across the jaw, thereby almost resulting in a mask-like arrangement (as pictured above).

On occasions, the bridges were stylized with embossing to mimic the mustache and the beard. As for its history of usage, there is a hypothesis that the Phrygian helmet was popular among the Macedonian cavalry of Philip (although Alexander preferred the Boeotian type for his crack cavalry). Later on, the Phrygian helmet was adopted by the phalanx pikemen of both Alexander and his Hellenistic successors.

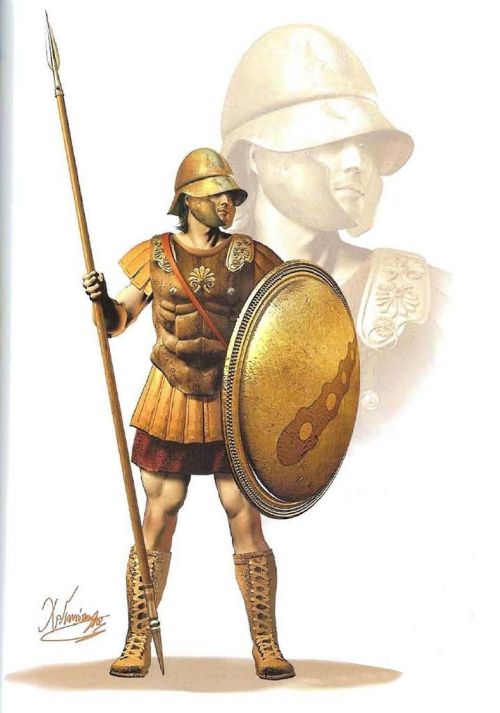

Boeotian Helmet (origins – circa 4th century BC)

The very origins of the Boeotian helmet are somewhat steeped in mystery, with its name derived from the region of Boeotia (whose capital was Thebes). One of the important mentions of this item comes from Xenophon himself, who recommended the Boeotian helmet for the head protection of cavalrymen.

According to some accounts, decades later, Alexander the Great heeded the advice, and consequently, the Macedonian elite cavalry (like the Hetairoi – Companions) adopted the Boeotian helmet while relegating the popular Phrygian variety. Curiously enough, the helmet, with various stylized features and plumes, was also adopted by the elites of the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek ruling classes in distant Central Asia.

In terms of design, the top part of the Boeotian helmet resembles the simpler Pilos helmet we discussed earlier. However, the distinguishing feature of the Boeotian pertained to its sloping metal rim that extended at the rear to protect the neck while also slightly projecting downwards at the front to deflect blows.

The rim additionally featured complex folds at various points for lateral protection to the face. In essence, the open design of the helmet didn’t limit the sight and hearing of the wearer (which was of critical importance for complex cavalry maneuvers). At the same time, the effective modifications allowed for adequate protection from incoming blows.

Konos Helmet (origins – circa late 4th century BC)

Another evolution of the Pilos helmet, the Konos was probably one of the last Greek helmets to be developed in the Classical period. Like its precursor, the Konos exhibited a slightly pointed shape. However, in place of the visor, the helmet had a brim projecting from the base to fit around the head and attachable ear guards that extended to the jaw.

Simply put, a full-fledged Konos helmet was a cross between a Pilos and a Boeotian type, but with additional ear guards. The equipment was mainly adopted by the Hellenistic armies after the death of Alexander.

Featured Image Credit: Johnny Shumate

Be the first to comment on "Know Your Ancient Greek Helmets: From Attic to Phrygian"