Introduction

Often heralded as Europe’s oldest city, Knossos is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site in Crete. In fact, the communal character of the site dates back to circa 7000 BC, with the establishment of the first Neolithic settlement in the area. By 4000 BC, the site boasted a Great House, which was possibly a precursor to the famed Palace of Knossos.

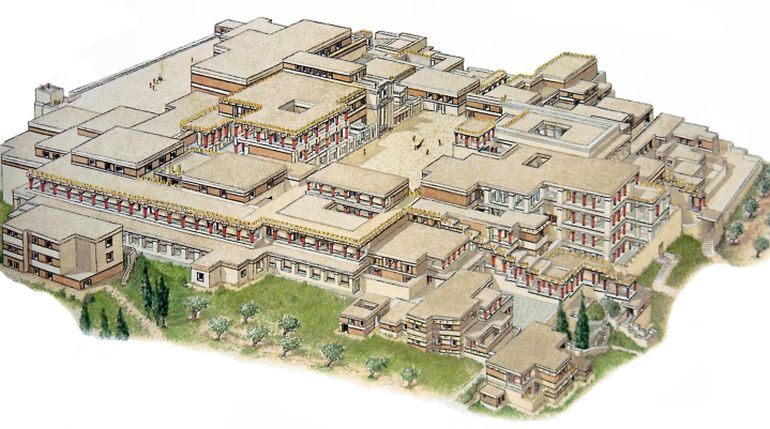

As for its historical significance, the Knossos Palace with its ‘labyrinth’ of spatial elements (including living spaces, storage rooms, and even working areas), was the ceremonial as well as the political center of the Minoan civilization. To that end, it has been estimated that the palace complex and its surrounding urban area boasted a population of around 100,000 at their peak, circa 1700 BC – thus becoming the mighty stronghold of Bronze Age Minoan Crete.

Contents

Reconstruction of Knossos

The video below represents the scale and scope of the massive Palace at Knossos with its intricate layout of passages and corridors, accompanied by a flurry of frescoes and pottery. The video in itself was sourced from flipped prof’s YouTube Channel.

In another nifty video, Invicta, with eminent archaeologist Josho Brouwers, gives us a tour of Knossos – via the incredible recreation made in the video game AC: Odyssey.

The Mythic Connection

In the vast (and often varied) scope of Greek mythology, one version of a legend talks about how it was the legendary King Minos who employed the Athenian architect and mathematician extraordinaire Daedelus to design his Palace of Knossos in a curious manner with perplexing spaces and pathways.

In another version of the story, King Minos directed Daedelus to contrive the famed Labyrinth itself, a complex spatial arrangement inside (or below) the palace with its fair share of confounding corridors.

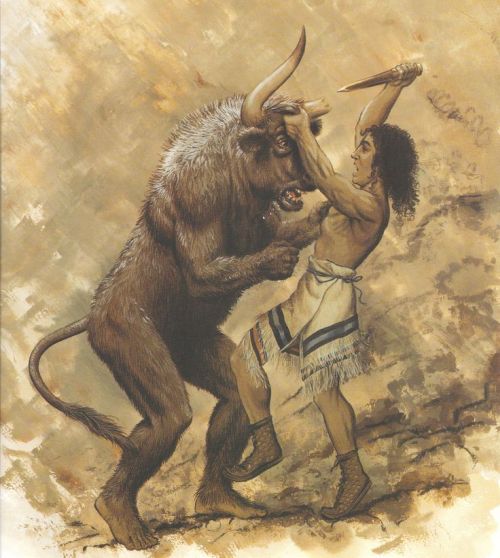

The famous story (possibly Athenian in origin) then goes on to mention how the monstrous Minotaur (hybrid half-man/half-bull) was locked inside the Labyrinth. This bizarre secret of the Palace of Knossos was guarded by imprisoning Daedelus and his son Icarus in a proverbial high tower.

Consequently, Daedelus fashioned a wing out of wax and bird feathers to escape from the clutches of Minos, but the legend takes a tragic turn with Icarus plunging to his death after flying too close to the sun.

Another parallel Athenian story talks about how Minos demanded tributes in the form of sacrificial victims from Athens, in order to feed the Minotaur, a monster born from an illicit affair of his wife with a white bull. But the hero Theseus put a stop to this gruesome practice, by killing the hybrid beast after going into the depths of the labyrinth and then escaping back with the aid of Minos’ daughter Ariadne.

The Legacy of the Minoan Civilization

Suffice it to say, many of the mainland Greece legends do not portray King Minos in a favorable light. But interestingly enough, a few other earlier mythic anecdotes depict Minos as a champion of wisdom and justice, who even went on to build the region’s first navy to defeat the local pirates.

In that regard, the actual historical legacy of the mighty Minoans can be derived from such tales that establish the hegemony of the island-state, thus hinting at its cultural predominance in the areas comprising mainland Greece and Crete. In fact, the early phase of the Bronze Age Mycenaean civilization in itself (mostly based in mainland Greece) was markedly inspired by the distant Minoans hailing from the island of Crete.

To that end, the earlier Mycenaean artworks, architectural patterns, and military arms, circa 1600–1450 BC, were very much similar to the contemporary Minoan styles – so much so that many early historians presumed the southern part of ancient Greece to be a colony of Bronze Age Crete.

But that was not the case. Rather the tangible influence of the Minoans of ancient Crete on the ‘mainland’ Mycenaeans probably came from sea-based trading and the exchange of materials between the two different cultures. To that end, it should be noted that the early Minoans used the Linear A syllabic script – which is still undecipherable and conveys a language entirely different from the Greek dialects (unlike Linear B).

So in a way, the early Minoans can be essentially considered ‘non-Greek’ who had a lasting influence on the perceived ‘Greek’ characteristics (like art and military) of the Mycenaeans.

The Wonder of The Minoan Palaces

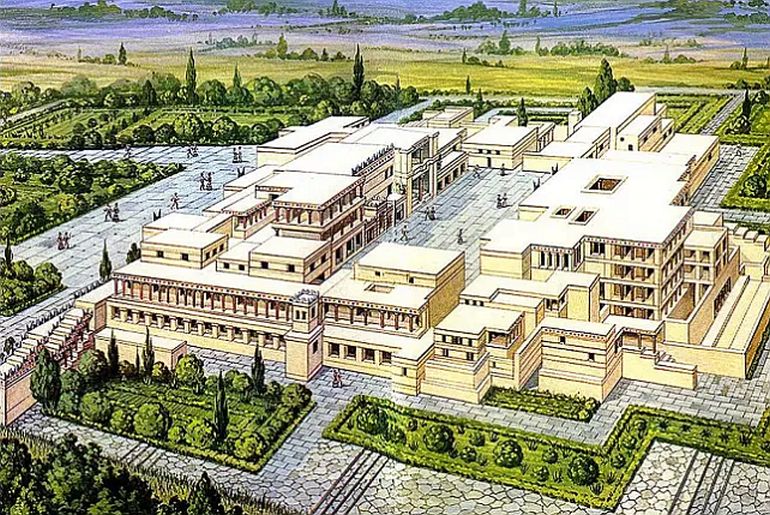

The adoption of large-scale architectural projects by the Minoans of Crete rather mirrored their profitable endeavors in maritime trade and even land-based commerce. In fact, the first Palace at Knossos (built circa 1900 BC) was constructed upon the remnants of an existing urban center. The scale of this massive building complex can be comprehended from the extensive coverage that encompassed a whopping 150,000 sq ft of the area – thus being equivalent to two-and-a-half American football fields.

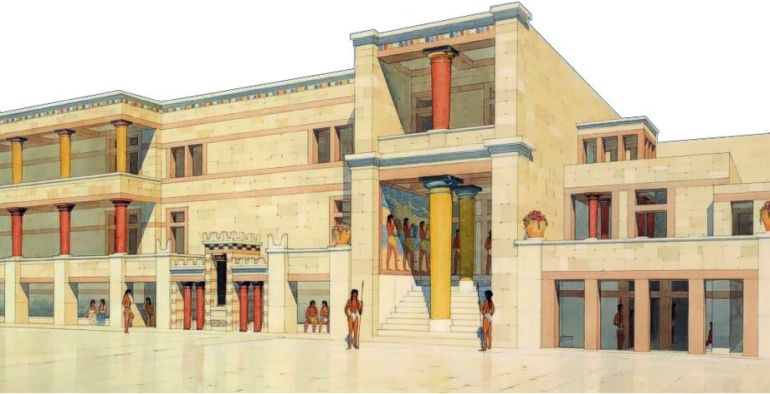

As for the core plan, the palace was built around a central courtyard and was accompanied by a flurry of storage areas, very thick walls, and perplexing basins. Considering these varied architectural elements, the Palace of Knossos was actually more than just a royal residence. It was rather conceived as a city-center complex, with structural attributes designed to serve civic, religious, and economic purposes.

Unfortunately, this first palace was destroyed by 1700 BC (probably due to an earthquake), and a second palace was built in the same location. Quite intriguingly enough, this newer construction was less bulky than its predecessor, thus losing out on many of the ‘monumental’ elements. Instead, the architects focused on intricate details bolstered by innovative structural designs.

For example, the Second Palace at Knossos had four main entrances, with the southern one rather notching it up on the grandiose level (comprising a corridor flanked by rich procession scenes) for the visitor.

The curious Throne Room also boasted impressive seating areas and vibrant frescoes (that possibly alluded to the unified central government of the Minoans during the period). Many historians have hypothesized that this Throne Room didn’t accommodate the court of the ruler, but rather served as a symbolic seat for the Snake Goddess of the Minoans.

The Mysterious End of Knossos?

Like many parcels of history, the climactic episode of the Knossos palace and its adjoining urban center is shrouded in mystery. According to historians, the Minoans were beset by cataclysmic events, circa 1450 BC, which could have entailed earthquakes around the small island or an invasion of the Mycenaeans from mainland Greece, or a combination of both.

However what we do know is that in the post-1450 BC period, the Palace at Knossos still formed an important political hub of the island, but its administration and military control were run by the aforementioned Mycenaeans. The archaeological evidence complementing this theory is derived from the Linear B inscribed clay tablets that were discovered at the eminent site.

In fact, many scholars had suggested that Knossos was possibly the capital of the ‘foreigner’ Mycenaeans, at least till 1375 BC when a fire destroyed the enormous palace. As for the architectural scope of the building, the mainland occupants did rebuild and renovate sections of the massive complex, while also bringing forth their own artistic style for new frescoes.

But these artworks tended to represent much of the stately affairs like heraldic devices and tribute processions, as opposed to the more lively, vibrant nature of the Minoan frescoes with their scenes of exotic animals and stylishly attired women.

In any case, the Mycenaeans of mainland Greece (and possibly their Minoan collaborators in Crete) were startlingly snatched away from the annals of history by 1180 BC, with the fall beginning with the destruction of their Pylos stronghold. Soon after, most of the other Mycenaean sites and settlements were also destroyed – and this sudden eclipse of a thriving Bronze Age culture is still one of the puzzling mysteries of time yet to be solved by historians.

Suffice it to say, there are debates in the academic world that relate to the hypothetical reasons behind this sudden ‘mass’ demise of a civilization (so much so that Greece was thrown into a dark age for almost three centuries, till the 9th century BC). Some of these conjectures bring up the familiar narrative of the invading Dorians and the mysterious forays of the ‘Sea People‘, while others hint at climatic changes and social revolutions.

And finally, we have a high-definition preview of the Palace at Knossos with spatial details like Queen’s Megaron with its famous Dolphin fresco. The video was sourced from ReaBits’ YouTube Channel.

Article Sources: Live Science / Interkriti

Books References: Mycenaean Greece, Mediterranean Commerce, and the Formation of Identity (By Bryan E. Burns) / The Mycenaeans c. 1650-1100 BC (By Nicholas Grguric)

Be the first to comment on "History and Reconstruction of the Palace of Knossos: The Stronghold of the Minoans"