Introduction

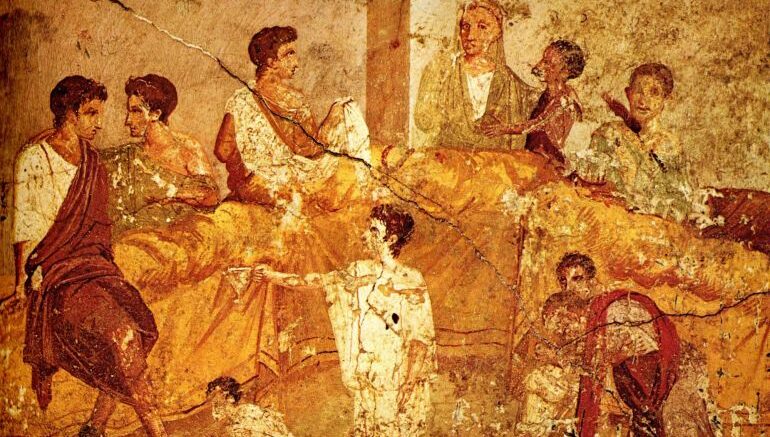

Ancient Romans had a penchant for doling out punishments in a rather theatrical fashion, with one pertinent example relating to the noxii, the criminals who were mainly accused of robbery, murder, and rape. At times, the noxii were simply used as living props who were unarmored (or sometimes dressed in ‘show’ armor) and then declared as opponents against the adept postulati, veteran gladiators armed with maces.

Consequently, these experienced gladiators made a gory demonstration of slowly dispatching the straggling criminals by spilling their blood on the sands of the arena. But this sadistic ‘fusion’ of theatricality and carnage was even taken to bizarre levels on a few occasions – as could be comprehended from poena cullei, a death penalty reserved for criminals who had committed the act of patricide (killing one’s father) or parricide (which refers to the killing of parents or close kin).

Poena cullei, roughly translating to ‘penalty of the sack’ in Latin, entailed the guilty party being sewn up in a leather sack or bag, along with other live animals, and then thrown into the river. Now historically, the first punishments reserved for crimes like parricidium (the blanket Latin term that covered the murdering a parent or close relative), documented from circa 100 BC, probably only involved the criminal being shoved into a sack, while his feet were weighed down by wooden clogs, and then thrown into the water.

However, by the early phase of the Roman Empire, the practice of including live animals in the grotesque scope was initiated. One of the famous examples harks back to the time of Emperor Hadrian (circa 2nd century AD), when the accused was tied up in a sack with an assortment of animals, including a rooster, a dog, a monkey, and a viper.

Contents

Plainly Weird or Deeply Symbolic?

Now such ancient practices naturally bring up the question – why were the Romans bent on devising strange punishments? Well, a part of the answer has to do with the act of parricidium and how it was perceived in the contemporary Roman world. To that end, the Romans considered the act of spilling the blood of someone who gave life to be gravely deplorable, so much so that it was associated with the very derailment of social order.

On this point, they viewed parricidium as a form of social corruption that could even taint the blood of wild animals who feasted upon the executed corpse of such a criminal. This intense notion was perfectly captured by one of the speeches made by Marcus Tullius Cicero, often considered one of the greatest Roman orators and prose stylists of his time, who was also a philosopher, politician, lawyer, and political theorist.

The entire speech was ironically prepared to defend his client Sextus Roscius accused of parricide, circa 80 BC, and one of its passages is quoted here –

They [previous Roman generations] therefore stipulated that parricides should be sewn up in a sack while still alive and thrown into a river. What remarkable wisdom they showed, gentlemen! Do they not seem to have cut the parricide off and separated him from the whole realm of nature, depriving him at a stroke of sky, sun, water, and earth – and thus ensuring that he who had killed the man who gave him life should himself be denied the elements from which, it is said, all life derives?

They did not want his body to be exposed to wild animals, in case the animals should turn more savage after coming into contact with such a monstrosity. Nor did they want to throw him naked into a river, for fear that his body, carried down to the sea, might pollute that very element by which all other defilements are thought to be purified. In short, there is nothing so cheap, or so commonly available that they allowed parricides to share in it.

For what is so free as air to the living, earth to the dead, the sea to those tossed by the waves, or the land to those cast to the shores? Yet these men live, while they can, without being able to draw breath from the open air; they die without earth touching their bones; they are tossed by the waves without ever being cleansed; and in the end, they are cast ashore without being granted, even on the rocks, a resting-place in death.

The Ritual Side of Affairs

As can be comprehended from such an elaborate idea behind the punishment of poena cullei, the Romans perceived the sin of parricide with symbolic elements. Consequently, the nature of punishment also took a ritualistic route.

To that end, according to 19th-century historian Theodor Mommsen’s interpretations (based on compilations of several sources), the person was first whipped with virgis sanguinis (a vague term which could have meant ‘red-colored rods’) and then his head was covered in a wolf-skin bag.

Wooden clogs were then placed on his legs and the guilty was shoved inside the namesake cullei (possibly a sack made of ox leather), along with other live critters. The sack was then sealed and the criminal was finally transported on a cart driven by black oxen to the nearest stream or even the sea.

Now in allusion to the practicality of such an outlandish scope, many later historians have talked about how the ‘ritual’ was probably not followed to the letter of the whimsical law. In that regard, the captors might have just opted for a simple leather bag instead of a wolf skin or used a common wine sack instead of special ox-leather sacks.

There are also confusions regarding the term virgis sanguinis, with hypotheses ranging from the person being whipped until he bled to the use of red-painted shrubs that were believed to purify his soul (instead of bleeding him). Furthermore, there may have been cases where the poena cullei was initiated only when the said person confessed his crime or was caught in the act (as opposed to meticulous legal proceedings).

The Occurrence of Poena Cullei

It should be noted that much like fustuarium (which required a rebellious soldier to be stoned or clubbed to death by his comrades), the punishment of poena cullei was reserved only for rare occasions. Roman historian Suetonius talked about how powerful emperors (like Augustus) even hesitated to authorize such dreadful penalties.

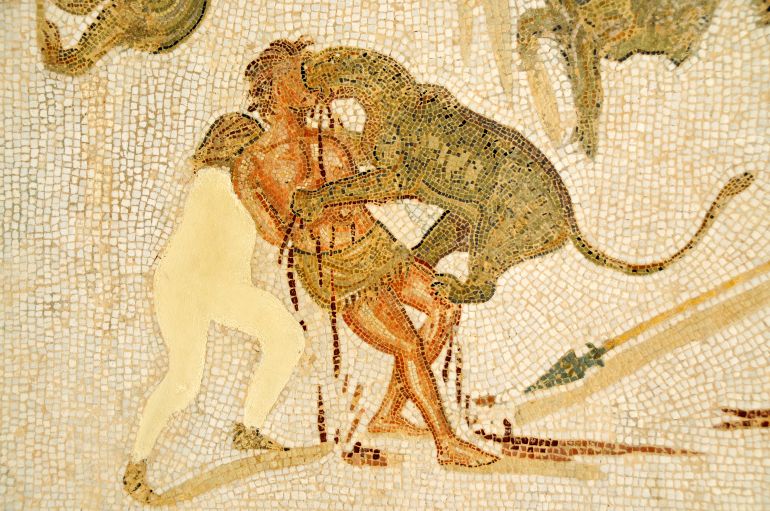

Interestingly enough, by the time of Emperor Hadrian, circa 2nd century AD, the punishment was possibly made optional, and the other unenviable outcome for the guilty related to being thrown into the arena with beasts.

And while the punishment gradually fell into oblivion by the 3rd century AD, later emperors like Constantine and Justinian sort of revived the dread of poena cullei, in a bid to bolster their Roman legacy when it came to legal institutions. For example, one of the texts from Corpus Juris Civilis, a massive collection of laws issued by Emperor Justinian, circa 530 AD onward, mentions –

A novel penalty has been devised for a most odious crime by another statute, called the lex Pompeia on parricide, which provides that any person who by secret machination or open act shall hasten the death of his parent, or child, or other relation whose murder amounts in law to parricide, or who shall be an instigator or accomplice of such crime, although a stranger, shall suffer the penalty of parricide.

This is not execution by the sword or by fire, or any ordinary form of punishment, but the criminal is sewn up in a sack with a dog, a cock, a viper, and an ape, and in this dismal prison is thrown into the sea or a river, according to the nature of the locality, in order that even before death he may begin to be deprived of the enjoyment of the elements, the air being denied him while alive, and interment in the earth when dead. Those who kill persons related to them by kinship or affinity, but whose murder is not parricide, will suffer the penalties of the lex Cornelia on assassination.

However, over time the punishment of poena cullei was relegated and finally abolished by the late 9th century AD. But parricide was still perceived as a severely deplorable sin in the later Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire), so much so that the ‘penalty of the sack’ was replaced by cruel immolation.

This was mentioned in Synopsis Basilicorum, a shortened version of the Byzantine law code Basilika, issued in 892 AD under the orders of Emperor Leo VI the Wise. But some forms of the punishment may have persisted in Europe (possibly in parts of Germany) till the late medieval period.

Sources: Tufts University

Book References: Pollution and Religion in Ancient Rome (By Jack J. Lennon) / Crime and Punishment in Ancient Rome (By Richard A. Bauman)

Be the first to comment on "Poena Cullei: The Bizarre Ancient Roman Punishment Reserved For Parricide"