Introduction

Venerated as the patron deity of Babylon itself, Marduk as one of the major Mesopotamian gods formed an important part of the Babylonian pantheon. This in itself suggests a shift in cultural prominence from the ancient Sumerians to the later Babylonians.

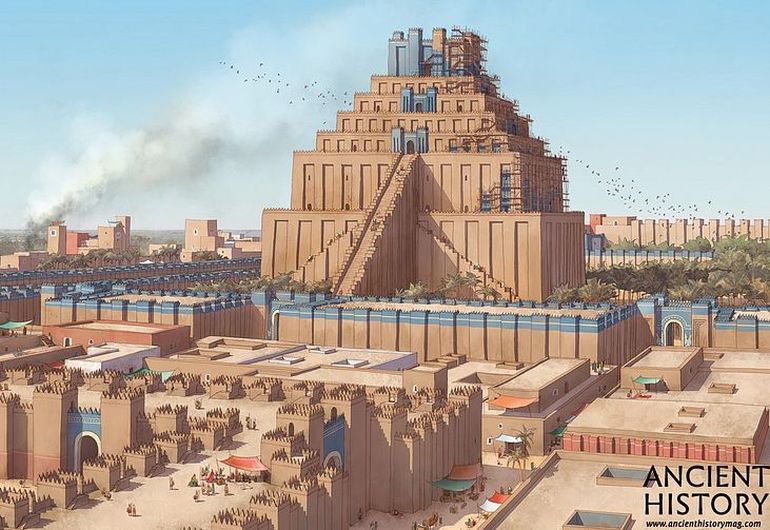

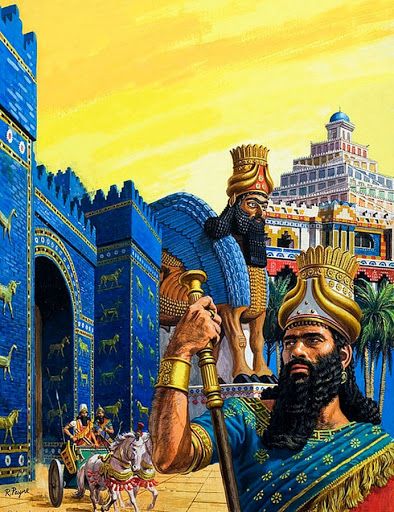

To that end, Marduk was portrayed as the very King of Gods, draped in royal robes, whose fields of ‘expertise’ ranged from justice, and healing to agriculture and magic. Historically, the famous ziggurat of Babylon was also dedicated to Marduk. And interestingly, the structure was probably the (literary) model for the Biblical Tower of Babel.

Contents

History and Origins of God Marduk

The origins of Marduk, like many ancient gods, are ambiguous – possibly harking back to a localized deity associated with water, judgment, and even magic. Some scholars have hypothesized that this local god was originally known as Asarluhi, a farmer’s deity represented by the spade. But to understand the rise of Marduk, one should be acquainted with the political scope of ancient Mesopotamia by circa 19th century BC.

During this time, Babylon as a city-state was a relative backwater when compared to other richer Neo-Sumerian (and Akkadian) cities like Larsa and Isin. Now in terms of the overarching Mesopotamian pantheon, Enlil and Enki (Ea – in Babylonian) were two of the supreme deities of southern Mesopotamia.

Among them, Enlil was often venerated as the ‘King of all lands’, the ‘Father of black-headed people’ (referring to Sumerians), and even the ‘Father of Gods’. As for Enki, the deity was worshipped as the ‘Lord of the Earth’, the creator god.

However, over the course of the next century, the Martu (Amorites) came into political power. Under Hammurabi’s leadership, they made Babylon the most influential city in all of southern Mesopotamia. Consequently, their patron god Marduk was promoted as the powerful mythical figure associated with rulership and even hegemony.

The name Marduk relates to marru roughly meaning ‘bull calf’; etymologically derived from amar-Utu or “immortal son of Utu” or “bull calf of the sun god Utu”. It should be noted that Utu, the divine god was said to be the creator of the laws that were prescribed in Hammurabi’s famous law code.

In the Babylonian pantheon, Marduk was perceived as the son of Enki (Ea), wherein the father amicably passes on his divine crown to his deserving son. At the same time, as a result of the rampant political changes, Enlil, the aforementioned Sumerian god, was gradually relegated to a secondary position, at least within the confines of Babylon (or in the Babylonian religion).

Politics and the Babylonian Creation Myth

Marduk’s rise in the Mesopotamian myths was rather proportionate to the political rise of Babylonia as a powerful city-state. His status as the head god of ancient Babylon was further cemented during the time of the Neo-Babylonian Period, circa 6th century BC. As for the reverse scope, the veneration of Marduk was also challenged by the worship of Ashur, the Assyrian god from northern Mesopotamia – when Babylonia as a regional power was superseded by the Assyrians.

According to historian Jeremy Black (as mentioned in his co-authored book Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary) –

The rise of the cult of Marduk is closely connected with the political rise of Babylon from the city-state to the capital of an empire. From the Kassite Period, Marduk became more and more important until it was possible for the author of the Babylonian Epic of Creation to maintain that not only was Marduk king of all the gods but that many of the latter were no more than aspects of his persona.

This Epic of Creation, also known as the Enuma Elish (or the Tablets of Creation), pertains to a Babylonian creation myth. Much of this text-based evidence was recovered by Austen Henry Layard in 1849 in various fragments. Boasting about a thousand or so lines, the lore was inscribed on seven known clay tablets in what is perceived as the Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform script.

While the first parts of the myth deal with Marduk’s birth, the Fourth Tablet of Enuma Elish rather extolls the kingship of Marduk as the ‘chief among gods’ –

They prepared for him a lordly chamber,

Before his fathers as prince he took his place.

“Thou art chiefest among the great gods,

Thy fate is unequaled, thy word is Anu!

O Marduk, thou art chiefest among the great gods,

Thy fate is unequaled, thy word is Anu!

Henceforth not without avail shall be thy command,

In thy power shall it be to exalt and to abase.

Established shall be the word of thy mouth, irresistible shall be thy command,

None among the gods shall transgress thy boundary.

Abundance, the desire of the shrines of the gods,

Shall be established in thy sanctuary, even though they lack offerings.

O Marduk, thou art our avenger!

We give thee sovereignty over the whole world.”

Worship of Marduk as the Patron Deity of Babylon

Interestingly enough, Marduk’s reign was perceived in a quite literal sense by the Babylonians, in contrast to a mythical rule. To that end, ancient Mesopotamians tended to view many of their gods as divine beings who were present on the physical plane inside the confines of the great temples (as opposed to the heavens or otherworldly realms).

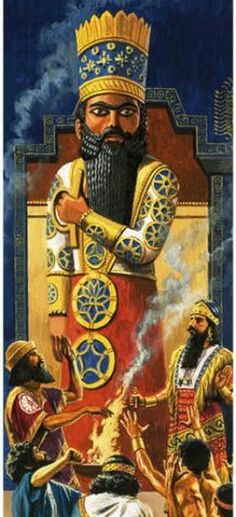

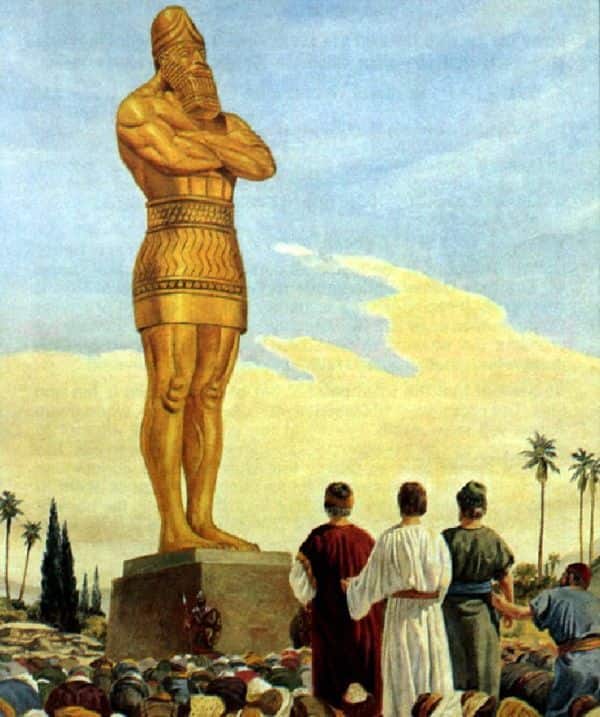

In that regard, Marduk was venerated as the true ruler, national god (or chief god), and protector of the grand city of Babylon. And as such, his golden statue was kept in the inner sanctum of Esagila, a massive temple complex. Simply put, Marduk as the patron deity, was by far the most important Babylonian god (akin to a supreme god), with his worship almost bordering on monotheism.

In fact, Marduk’s cult was so deeply entrenched in the consciousness of the Babylonians that even their conquerors had to pay respects to the powerful god. For example, one possible ritual of the Kassites (who conquered Babylon by the 15th century BC) entailed how the new king, at his coronation, had to ‘take the hands of Marduk’ either in a literal way by clasping the hands of the statue or in a figurative manner by assuming his kingship under the guidance of the mythical ruler.

Similarly, after the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in the 6th century BC, Cyrus, the first Achaemenid Persian king, promoted himself as the ‘chosen of Marduk’ who was destined to rule the city of Babylon.

The Bel Connection in the Babylonian Pantheon

Interestingly enough, by circa 1000 BC, Marduk was probably referred to simply as Bel (meaning ‘lord’) by many of his worshipers. Now given how the Mesopotamia pantheon was a religious extension of the ancient cultural overlap (of Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and other groups), Bel was possibly an aspect of Marduk that was a composite of other gods like Enlil and Dumuzid.

Even more intriguing are the apocryphal narratives that bring forth Bel as a ‘character’ in the additions to the Biblical Book of Daniel. Furthermore, the Book of Jeremiah of the Old Testament directly mentions both Marduk and Bel in the prediction of the fall of Babylon –

Babylon will be captured;

Bel will be put to shame,

Marduk filled with terror.

Her images will be put to shame

and her idols filled with terror.

Lineage and Myths of Marduk

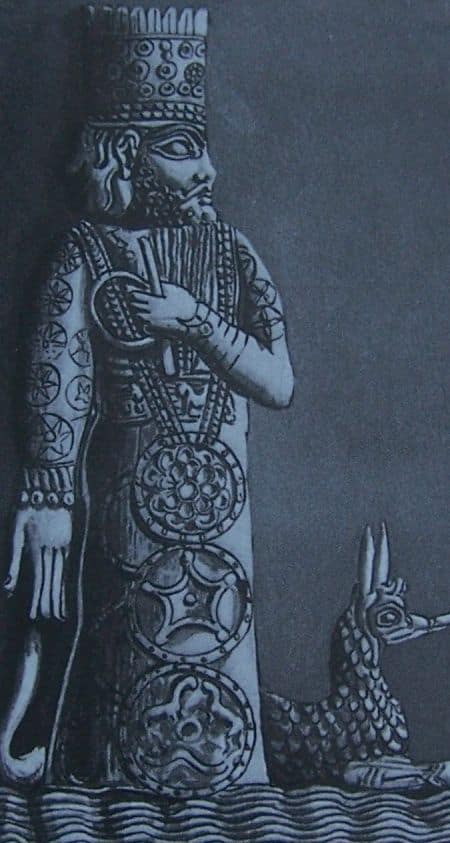

On the mythological side of affairs, Marduk was the son of Enki (as mentioned in the previous entry). He was responsible for slaying Tiamat, the primeval goddess who took a dragon form to challenge many of the younger gods (as an act of revenge, instigated by the murder of her husband Apsû).

Marduk also defeated the god Quingu (or Kingu – Tiamat’s new consort) in single combat, while also decimating the enemy host of many monsters and ‘poison-filled’ serpents. These heroic acts propelled him to the forefront of the new order of gods – who, in turn, unanimously proclaimed Marduk as their new king.

Then comes Marduk’s role as a creator god, as he proceeded on to ‘source’ the rivers Tigris and Euphrates from the slain goddess’ eyes, while her body was carved up to create heaven and earth (in some myths, the earth is created by both Marduk and his father Enki, while others omit Enki from the narrative).

More importantly, under Marduk’s leadership (or directive), the first human is said to have been created – from the remains of the executed body of the god Quingu. The first generation of these humans is tasked with presumably servile burdens that would free up the time of the gods for higher purposes. According to revised Babylonian texts, Marduk also created the first city Eridu, which is incidentally one of the earliest known cities of Mesopotamia.

Attributes of Marduk

As prescribed in the Enuma Elish (Tablets of Creation), Marduk was revered as the King of the Gods by the Babylonians. Described as draped in his royal robes, the regal Marduk was also considered the god of storms and divine judgment. Interestingly enough, in many associated myths, Marduk was venerated as a deity of agriculture and healing, with the former aspect possibly being connected to his origins as the local agricultural god Asarluhi.

And like we mentioned before, in his Bel (‘Lord’) aspect, Marduk might have been the composite of Enlil and Dumuzid. Therefore combining these deities’ qualities, Bel was also worshiped as the god of order and destiny.

Marduk’s Statue and the Prophecy

Now beyond the metaphysical concept of an ancient god, Marduk (like many Mesopotamian patron gods) was perceived as having discernable powers in our real world. This element of potential and capacity was directly attributed to the cult statue of Marduk that was kept in the inner sanctum of the Esagila temple complex.

Simply put, in Babylonian culture, the statue was venerated as the physical manifestation of Marduk himself. Consequently, in festivals like the Akitu (New Year), people of the city were required to carry the statue to the scenic outskirts for the ‘recreation’ of Marduk. On the other hand, the celebrations for New Year were unceremoniously canceled when the Marduk statue was stolen by foreign powers.

Pertaining to the latter, it was often a tactic of many proximate powers to take away the statue from Babylon to their native lands, as a show of divine authority over the defeated Babylonians. The Marduk Prophecy, an Assyrian document from circa 712-613 BC (based on an older Babylonian story), refers to such incidents as the ‘travels’ of Marduk and prophesied its return at the hands of a strong Babylonian king.

However, finally, the Achaemenid emperor Xerxes, in response to a rebellion in Babylon (circa 485 BC), had the Marduk gold statue destroyed to fill up the royal exchequer.

Other Online Sources: Ancient Encyclopedia / ORACC

Featured Image: Artwork by yigitkoroglu (DeviantArt)

Be the first to comment on "Marduk: The Mighty Storm God of Babylon"