Popular culture has been kind to the historical episode of the Battle of Thermopylae but with romanticized anecdotes intertwined between the actual events that took place before and during the particular military encounter.

One apt example would pertain to King Leonidas I himself, who was probably closer to the age of 60 at the time of the battle, as opposed to what Hollywood would make us believe (by contrast, Xerxes was only 38 years old at the time of the battle).

So without further ado, let us try to sift some of the facts from fiction, and have a gander at the 10 misconceptions one should know about the Battle of Thermopylae – a momentous episode of history that stands testament to the importance of tactics and bravery in war.

Contents

- The Invincible Persian Record

- The Spartan Prowess

- The Persian Archer and the Pun

- The Immortals

- The Numbers Game: The Greek Force vs The Persian Army

- More of a Tactical Stand than a Final Stand

- Spartan Maneuvering and Feigned Retreats – The First Day

- Suprise on the ‘Guarded’ Pass – The Second Day

- Last Day Strategy of the Spartan King Leonidas

- The Line Between History and Legend

The Invincible Persian Record

While popular history is not favorable to the ancient Achaemenid Persians when it comes to Greco-Persian wars, it should be noted that the Persians had quite a reputable record against the Greeks in battles prior to the Marathon episode in 490 BC.

In that regard, the Greeks were not able to stop the Persian juggernaut in the four clashes out of five that took place on open land during the preceding Ionian revolt. The fifth clash was a chaotic affair with a night-time ambush on the part of the Greeks.

But beyond just the numbers game, it was the Persian combined-arms style of mass combat that allowed them to regularly triumph over the Greek armies. To that end, the ‘flexible’ Persians tended to prefer archery over solid formations of infantrymen locking their shields.

Furthermore, the Achaemenid Persian Empire also utilized their cavalry for flanking and even at times as shock troops to disperse their foes – as evidenced by the final battle of the Ionian revolt at Malene that caused the ‘Greeks to flee’ due to a last-moment cavalry charge (according to Herodotus).

The Spartan Prowess

However, the previous encounters were mainly fought by the Anatolian Greeks. The ‘mainland’ Spartans on the other side not only emphasized hoplite-based warfare but rather took the tactical scope of ‘shoulder-to-shoulder’ combat to a whole new level of organization and discipline.

According to much impressed Thucydides, at the commencement of the battle, the Spartan army officers grouped the hoplites and their lines started moving forward (with some wearing wreaths), while the king began to sing one of many marching songs composed by Tyrtaios. He was complemented by pipers who played the familiar tune, thus serving as a powerful auditory accompaniment to the progressing Spartan army.

Interestingly, as with many Greek customs, there might have been a practical side underneath this seemingly religious veneer. To that end, the songs and their tunes kept the marching line of Greek hoplites in order, which entailed a major battlefield tactic – since Greek warfare generally involved closing in with the enemy with a solid, unbroken line. This incredible auditory scope ended in a crescendo with the collective (yet sacred) war cry of paean, a military custom that was Dorian in origin.

Now one major misconception relates to how Greek hoplites fought and charged in tight unbroken formations. But in reality, many battles didn’t even come to the scope of ‘physical contact’. In other words, a hoplite charge was often not successful because the citizen soldiers tended to break their ranks (and disperse) even before starting a bold maneuver. As a result, the army that held its ground often emerged victorious – thus exemplifying how morale was far more important than sheer strength in numbers.

And this is where the Spartans shined – since they demonstrated their penchant for keeping up their own morale, especially when the massed hoplite charge was a chaotic and brutal affair. Xenophon, in spite of being an Athenian, heaped his praise on the Spartans by calling them – “the only true craftsmen in matters of war”.

The Persian Archer and the Pun

And while the Spartans had their well-trained hoplites, the oft-missed military fact is that Persians had their well-trained archers. To that end, the bow was the national arm of the ancient Achaemenid Persian Empire. Interestingly, even some of the regular Persian infantry, equipped with wicker shields, short spears, and double-edged daggers, carried their bows and a fair share of arrows in a gorytos, a case that housed both the weapon and the projectiles.

As for the dedicated Persian archers, they probably carried composite bows that were rather large by contemporary standards. According to Xenophon, the Persian archers even outranged the Cretans, who were considered specialists in archery from the Greek domain. And beyond just the bow itself, much of the improved shooting probably had to do with the better archery techniques and the lighter arrows preferred by the Persians.

Interestingly enough, the Persians also had the advantage in their ‘archers’ of a different kind. That is because the gold daric coin (dareikos in Greek) was popularly referred to as the ‘archer’ by the Greeks – since the currency depicted the image of a Persian royal armed and ready to shoot his bow. And thus many of the Achaemenid Great Kings could boast about how they could conquer Greece with their archers, with a possible pun in the offering.

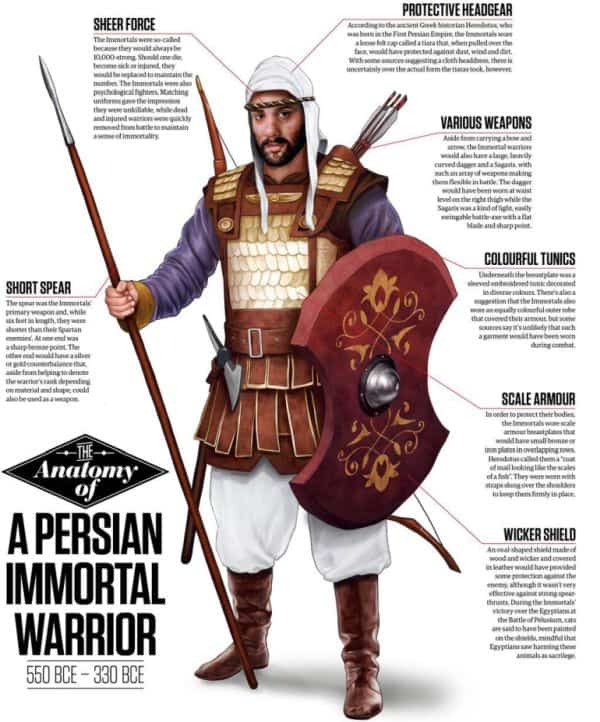

The Immortals

The ancient Persians almost had an obsession with the number ‘thousand’, and as such their regiments were theoretically divided into thousand men known as hazarabam (hazara denoting thousand). The decimal system was also upheld when ten such regiments were combined to form a division (baivarabam) of 10,000 men.

The so-called ‘Immortals’ or Amrtaka (in Old Persian) were the chosen baivarabam of the Persian king, and their scope of ‘immortality’ seemingly stemmed from their constant number – which was always kept at 10,000 (according to Herodotus).

In other words, the casualties in this elite division might have been replaced as soon as possible with the best candidates from other Persian baivarabam. As Herodotus goes on to describe these Athanatoi (Immortals) in the battle of Thermopylae (480 BC) –

…a body of picked Persians under the leadership of Hydarnes, the son of Hydarnes. This corps was known as the Immortals, because it was invariably kept up to strength; if a man was killed or fell sick, the vacancy he left was at once filled, so that the total strength of the corps was never less – and never more – than ten thousand.

Of all the troops in Persian army, the native Persians were not only the best but also the most magnificently equipped; their dress and armor I have mentioned already, but I should add that every man glittered with the gold which he carried about his person in unlimited quantity. They were accompanied, moreover, by covered carriages full of their women and servants, all elaborately fitted out. Special food, separate from that of the rest of the army, was brought along for them on dromedaries and mules.

The Greek historian further mentions their rich attire –

The dress of these troops consisted of the tiara, or soft felt cap, embroidered tunic with sleeves, a coat of mail looking like the scales of a fish, and trousers; for arms they carried light wicker shields, quivers slung below them, short spears, powerful bows with cane arrows, and short swords swinging from belts beside the right thigh.

As can be comprehended from such accounts, the Persian Immortals were probably very different from the oddly sinister manner in which they were depicted in the movie 300.

In fact, such elite divisions tended to flaunt their vibrant and rich uniforms and armaments – as is evident from their accounts of carrying spears with golden pomegranates, silver pomegranates, and even golden apples. The latter-mentioned spears were carried by the king’s own bodyguard unit of 1,000 men – known as arstibara, nicknamed the ‘Applebearers’.

The Numbers Game: The Greek Force vs The Persian Army

The most popular misconception about the Battle of Thermopylae probably relates to the numbers fielded in the battle. In fact, in many corners of popular culture, the encounter is often depicted as 300 Spartans (aided by their rag-tag group of allies) versus over a million vast Persian army. These numbers, however, are without a shred of doubt exaggerations based on flawed historical accounts, modern-day pop culture sensationalism, and of course romanticism.

In fact, during the period (circa 480 BC), Sparta alone could have fielded over 8,000 of its free adult citizens as hoplites. But historically they could not bring forth their entire army at the Battle of Thermopylae due to religious observances (like the feast of Apollo Karneia) and the Panhellenic Olympic Games.

And while these reasons may seem bizarre to our modern sensibility, ancient Greeks formulated strict rules when it came to religious activities – so much so that the Spartans didn’t even aid the Athenians (in time) at the momentous Battle of Marathon (during the First Persian invasion), ten years before Thermopylae.

This brings us to the question – how many men did each side have in this incredible encounter? Well interestingly enough, the Greek historian Herodotus – the man who claimed that the Persian forces numbered over a million troops, clarified how the Greek side at least had 5,200 men (as opposed to only 300 Spartans).

The figure included the over thousand perioikoi (the free yet non-citizens of Sparta), Greek contingents from Mantineans, Tegeans, Arcadians, Corinthians, Thespians, and even Thebans (who probably numbered over 400), along with groups of other Peloponnesians. Modern historians also add helots to this array of forces, thus bringing the total number of Greeks probably over 7,000 men.

The Persians on the other hand, while undoubtedly having their numerical superiority, would have had logistical constraints to even field half a million men, considering the size of the Persian navy. To that end, modern scholarship suggests that the Persians could have carried forth around 260,000 men in their 1,300 triremes.

But only a percentage of them were actual soldiers, with others serving the duties of oarsmen, baggage carriers, and camp followers. To summarize, the plausible figure range for the Persian force at the Battle of Thermopylae was somewhere between 80,000 to 100,000 men.

More of a Tactical Stand than a Final Stand

Another popular misconception (although more valid) about the Battle of Thermopylae relates to how Leonidas made his last stand in the encounter. And while this statement holds true for the final day of the battle, the initial decision made by Spartan King Leonidas and his commanders to hold the coastal mountain pass at Thermopylae was probably more of a logical tactic than just a noble warrior’s duty.

Now geographically, Thermopylae was probably the easiest access point from Thessaly (in the north) into Central Greece – thus suggesting its unique strategic value to the Persian advance. Furthermore, the very position of Thermopylae reveals the ‘force-multiplier’ tactics of the Greeks, with the defensive area being only around 15 m (or 49 ft) in width. This mountain pass also secured a location that was nearby to a smaller mountain passage on its left and the sea to its right.

In fact, part of Leonidas’ strategy to defend his position at what is known as the ‘Middle Gate’ was fueled by the presence of an existing (although dilapidated) wall that was built by the local Phokians. And while the Greek forces were busy repairing the makeshift fortification, Leonidas also took heed of many of the flanking routes that bypassed the gates. One of these treacherous pathways, known as the Anopaia path, was actually guarded by around 1,000 Phokian hoplites under the directive of the Spartan king.

Spartan Maneuvering and Feigned Retreats – The First Day

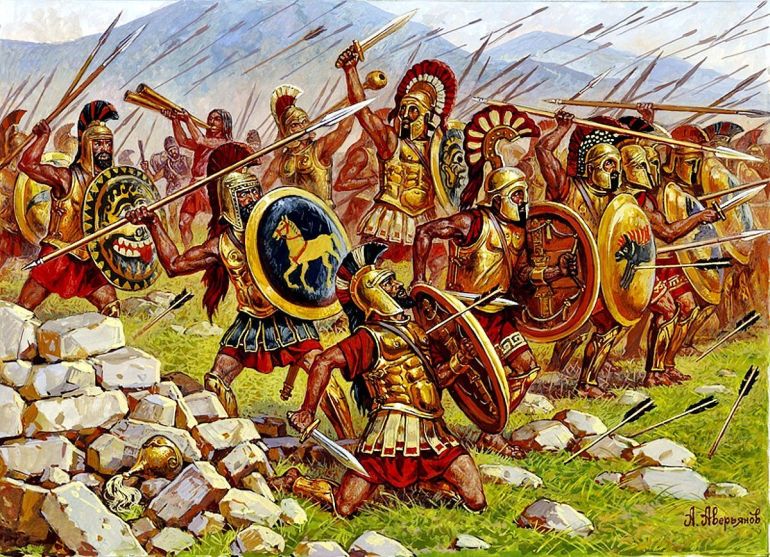

It is no hidden secret that the sheer level of training, high morale, and phalanx formation of the Spartans allowed them to be steadfast in the face of an overwhelming Persian invasion force on the first day of the battle. The Persian assault didn’t prove to be successful for Xerxes, with the heavy defeat rather exacerbated by the constricted landscape of the pass (which countered the Persian advantage in numbers).

And Herodotus, while being vague on casualty figures, talked about how the longer spears of the Greeks were actually better suited to the task of engaging the enemy than the shorter spears of the Persian infantrymen. We are also told that the Greeks fought in relays, with contingents allowed to take a break from the front-line – thus making the defense more effective with fresher batches of men.

However, while much has been said about Spartan ‘obstinacy’ in the face of imminent danger, one should also understand that Sparta among most Greek city-states recognized the practicality of warfare. In many ways, their army was the closest to what can be termed a professional military force in the contemporary ancient world.

To that end, an often overlooked ploy in the Battle of Thermopylae related to how the Spartans not only held their positions but also made feigned retreats, to lure the Persians into tighter terrains. And once a large enemy force was cut off from the main body, the Greeks fought by turning around and using their superior melee skills (along with the element of surprise) to destroy them in a piecemeal fashion. This Greek strategy of feigning retreats also didn’t allow the famed Persian archers to focus on stationary targets of massed hoplites.

Suprise on the ‘Guarded’ Pass – The Second Day

The second day of the Battle of Thermopylae also played out in a similar fashion to its previous day – as the Greeks held their positions, while the Persians were unable to make any significant breakthrough. But then came the famous episode of Ephialtes and how he presented himself before the Persian command as a guide for the ‘secret’ path that would bypass the main Greek force and catch them unawares at the rear.

But as we fleetingly mentioned before, once again contrary to popular notions, Leonidas was already aware of the existence of such a path. In fact, this very passage, known as the Anopaia path, was actually guarded by the local Phokian contingent that had around a thousand men.

But unfortunately for the Greeks, the Persians sent their elite Immortals (presumably guided by Ephialtes), who probably set out in their full numbers to make a deciding impact in the conflict. After leaving the Persian camp, by the dawn of the third day, they reached the Phokian Greek position, with both sides rather surprised by the presence of each other.

And while the Phokian citizen-militia were known for their competent vigilance over the local lands (at least under Greek control), they were simply no match for the elite corps of Persian Immortals. In the following encounter during the battle, the highly-trained Immortals quickly overwhelmed their opponents by focused arrow-fire volleys.

The Phokian militias rapidly retreated to the higher grounds, and then most of them pleaded for their lives to the arriving Persian forces. Interestingly enough, the Immortals, instead of dallying with the Phokian forces, continued their calculated advance into the rear part of the Greek lines, thus ultimately turning the tide of the battle.

Last Day Strategy of the Spartan King Leonidas

After Leonidas heard the news of their vulnerable position in the battle, he once again resorted to a tactical decision that ironically entailed making a last stand. In essence, while later tales extolled the virtues of defiance and braveness in the face of imminent death (and justifiably so), Leonidas and his men stayed behind not for their posthumous praises, but for covering a significant part of the army that had over 5,000 men.

To that end, when it comes to strategy, the overall retreat of the entire Greek army, while being one of the available options, wouldn’t have been a feasible one. This is because the Persian cavalry by this time could have easily overtaken them and cut them off in a piecemeal manner. Another factor to consider is that Spartan law in military matters dictated that retreat for the royal guard (hippeus) should be avoided.

Simply put, to Leonidas (who was also certainly conscious of Spartan military customs), it was the matter of saving a significant part of the defending force by rear-guard action or making a prolonged last stand with the entire army that would have caused a greater number of Greek casualties. Suffice it to say, he bravely (and wisely) chose the former. And this allowed the majority of the defending Greek soldiers to escape from the clutches of Xerxes at the Battle of Thermopylae.

The Line Between History and Legend

But once again, as opposed to popular notions, Leonidas did not make his last stand with just a small force of 300 Spartans. They were probably aided by their helot attendants (possibly numbering over 300), along with around 700 Thespians and 400 Thebans (who, according to Herodotus were held against their will, although the practicality of warfare suggests otherwise).

And instead of occupying the narrow pass, Leonidas ordered his assembled rear guard to advance to a broader area, knowing well that their previously guarded position was now vulnerable to the approaching Immortals from behind. The Greek army of hoplites made their characteristic slow advance with shield walls, singing of paean hymns, and ritual sacrifices.

Interestingly enough, the orthodox method of marching was soon done with, as Persian arrows began to fall among the ranks. Leonidas, cognizant of the urgency of the situation, ordered his men to sprint along the last few yards and quickly close the gap between the enemy and themselves. This short spurt once again denied the Persians to shoot their concerted volleys at relatively immobile targets.

And once the armies met, a furious clash ensued, which resulted in even greater Persian casualties (according to Herodotus). But unfortunately for the Greeks, Leonidas met his demise in the chaotic melee engagement, and his guards valiantly defended the fallen body of their king to the last man.

Finally, the Spartans decided to fall back to the narrow pass, and made their stand on a hillock (with broken spears and swords), though the remaining Thebans possibly endeavored to surrender themselves and their weapons to the enemy. Thus ended the Battle of Thermopylae, resulting in a pyrrhic Persian victory and a gutsy Greek defeat. According to Herodotus, the Great King Xerxes lost 20,000 of his Persian troops, while the Greeks lost 4,000 of their troops – but modern estimates tend to lower both numbers.

In essence, the last stand was not just about the heroics of 300 Spartans but rather encompassed the gutsy feat of over a thousand Greeks that included both free-men hoplites and lightly armed slaves. In fact, Herodotus even grudgingly mentioned the corpses of helots lying on the battlefield, thus suggesting how some of these slaves willingly laid down their lives for a concerted military effort.

Sources: Ancient History Encyclopedia / Reed College / Livius

Book References: Thermopylae 480 BC: Last Stand of the 300 (By Nic Fields) / The Persian Army 560 – 330 BC (By Nick Secunda) / The Battle of Thermopylae: A Campaign in Context (By Rupert Matthews)

Featured Image Credit: aditulaudis

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "Battle of Thermopylae: 10 Misconceptions You Should Know"