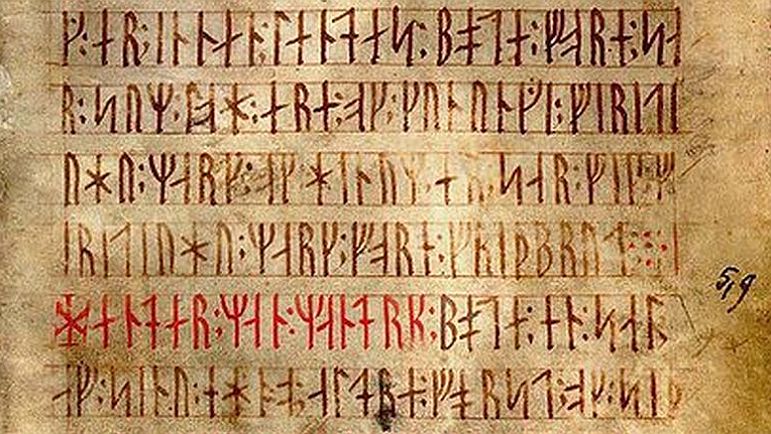

Codex Runicus, the medieval manuscript dating from circa 1300 AD, comprises around 202 pages composed of runic characters. Known for its content of the Scanian Law (Skånske lov) – the oldest preserved Nordic provincial law, the codex is also touted to be one of the very rare specimens that have its runic texts found on vellum (parchment made from calfskin). And interestingly enough, as opposed to Viking Age usage of runes, each of these ‘revivalist’ runes corresponds to the letters of the Latin Alphabet.

Now while a significant section of the Codex Runicus covers the Scanian Ecclesiastical Law (pertaining to Danish Skåneland), the manuscript also chronicles the reigns of early Danish monarchs and the oldest region along the Danish-Swedish border. But most interestingly, the last page of the codex also contains what can be defined as the oldest known musical notations written in Scandinavia, with their non-rhythmic style on a four-line staff.

One such Norse song verse, more famously known in modern Denmark as the first two lines of the folk song Drømde mig en drøm i nat (‘I dreamt a dream last night’), is presented in the video below, performed under the tutelage of renowned Old Norse expert – the ‘Cowboy Professor’ Dr. Jackson Crawford. One can also listen to the short instrumentation of this old Norse song by clicking here.

Lyrics (Old Norse):

Drøymde mik ein draum i nótt

um silki ok ærlig pell,

um hægindi svá djupt ok mjott,

um rosemd með engan skell.

Ok i drauminom ek leit

sem gegnom ein groman glugg

þá helo feigo mennsko sveit,

hver sjon ol sin eiginn ugg.

Talit þeira otta jok

ok leysingar joko enn —

en oft er svar eit þyngra ok,

þó spurning at bera brenn.

Ek fekk sofa lika vel,

ek truða þat væri best —

at hvila mik á goðu þel´

ok gløyma svá folki flest´.

Friðinn, ef hann finzt, er hvar

ein firrest þann mennska skell,

fær veggja sik um, drøma þar

um silki ok ærlig pell.

Lyrics (English translation):

I dreamed a dream last night

of silk and fair furs,

of a pillow so deep and soft,

a peace with no disturbance.

And in the dream I saw

as though through a dirty window

the whole ill-fated human race,

a different fear upon each face.

The number of their worries grow

and with them the number of their solutions —

but the answer is often a heavier burden,

even when the question hurts to bear.

As I was able to sleep just as well,

I thought that would be best —

to rest myself here on fine fur,

and forget everyone else.

Peace, if it is to be found, is where

one is furthest from the human noise —

and walling oneself around, can have a dream

of silk and fine furs.

And in case you are interested, the famous folk song (partly derived from the oldest secular Norse song) is presented below. It was performed by the Danish singer Louise Fribo.

Reverting to the Codex Runicus itself, many scholars do not consider the manuscript as a natural progression of runic culture (that was prevalent during the Viking Age) into the later Latinized era of medieval times in Europe. Instead, the literary scope is perceived as a revivalist work that sort of counteracted the rising cultural influence of Western Europe in Scandinavia. To that end, as we mentioned earlier in the post, the runic script in itself was written with the help of 27 characters that corresponded to the phonemes of the Latin alphabet.

These medieval runic ‘letters’ found in the Codex Runicus were based on the Younger Futhark, a runic alphabet with only 16 characters that were mainly used during the Viking Age and its succeeding decades (early 8th to 12th centuries). And from the historical perspective, in spite of the introduction of Latin letters in parts of Scandinavia (by the 13th century), the feudal working class – including the farmers, artisans, and traders, continued to write in runic scripts, for both communicating and marking their goods.

In fact, the Latin alphabet was perceived as a foreign language in most parts of Sweden till the 16th century. Related to this ‘native’ scope, many of the Icelandic manuscripts till the 19th century featured medieval runes and entire rune poems. As noted Swedish runologist Sven B. F. Jansson said –

We loyally went on using the script inherited from our forefathers. We clung tenaciously to our runes, longer than any other nation. And thus our incomparable wealth of runic inscriptions also reminds us of how incomparably slow we were – slow and as if reluctant – to join the company of the civilized nations of Europe.

Sources: The Medieval Nordic Legal Dictionary / ApManuscripts

Be the first to comment on "The World’s Oldest Known Secular Norse Song"