Introduction

Often counted among the better-known medieval Christian military orders, the Knights Hospitallers or the Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem (‘Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani’ in Latin) were older than both Templars and the Teutonic Knights.

And unlike the latter two orders, the Hospitallers maintained their bulwark against the ascendant Islamic realms (like Mamluks and Ottomans) long after the decline of the Christian military presence in the Levant. So without further ado, let us take a gander at ten things one should know about the Knights Hospitaller (or the Order of Saint John).

Note* – In this article, we will mainly focus on the military and organizational structure of the Hospitallers till the late 13th century. After the fall of Acre (circa 1291 AD), the Knights Hospitaller shifted to the island of Rhodes and thereafter were better known as the Knights of Rhodes.

Contents

- Introduction

- Preceding the Crusades

- The Different Nationalities of the Knights Hospitaller

- The Motivation To Join Ranks

- The Knights of Knights Hospitaller?

- The Alleged ‘Ancient’ Legacy

- The Religious Enthusiasm And Discipline

- The ‘Simple’ Armor

- The Various Arms

- The Charge of the Knights Hospitaller

- Conclusion – The Practicality of Tactics and Strategy

Preceding the Crusades

Unlike their ‘rivals’ like the famed Templars and Teutonic Order, the Hospitallers as an order (Order of St John of the Hospital of Jerusalem) existed before the commencement of the First Crusade in 1099 AD. Its original patrons included a few Italian merchants hailing from the Amalfi coast.

These traders formed the charitable organization (possibly by circa mid-11th century) as a means to provide aid to the traveling Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land, incredibly after obtaining the required permits from the Egyptian Fatimid sultan.

By the penultimate decade of the 11th century, the institution rather thrived under the leadership of the Benedictine monks from the Church of Santa Maria Latina, which led to the establishment of two separate hospices in Jerusalem – one for men and the other for women.

After the First Crusade, the network of hospitals was expanded under favorable conditions put forth by the Crusader overlords of Jerusalem and the surrounding areas. Essentially, the religious orders, especially the Hospitallers, were given free rein to take over other hospitals and logistical centers in the region, with the growing influence of the French who superseded the Italians.

Consequently, the Hospitallers became more autonomous in nature and their endeavors gradually delved into other affairs that went beyond caring for the sick. To that end, it was only in the latter half of the 12th century that the Hospitallers began to gradually expand into military spheres, possibly inspired by the Templars who were originally formed to protect the Christian pilgrims from local bandits.

The Papacy rather encouraged this ‘newfound’ martial side to the religious orders, given the latter’s decades of experience in organizational capacity and logistical management in the Holy Land. Thus a religious veneer was applied to the ‘warrior-monks’ and their (often remarkably courageous and sometimes excessively brutal) feats were perceived and advertised as ‘acts of love’.

As for the Knights Hospitaller, their extended military arm helped them to bolster their autonomous political and economic domains not only in the Outremer and the Levant but also across Europe.

The Different Nationalities of the Knights Hospitaller

The typical profile of a would-be ‘warrior monk’ of the Knights Hospitaller in the Outremer pertained to a young (and mostly fit) man who generally came from a free background. That is not to say that all of these men were of noble birth, especially in the 12th century. The majority of the members hailed from continental France and also England, while the Hospitallers were also widely recruited from the regions of Bohemia and Hungary.

Pertaining to the latter, the ordinary brethren tended to be composed of the native Hungarians, Croats, Bosnians, and even German settlers, while the leadership positions were often taken by the French and Italians. Interestingly enough, in the Iberian peninsula (Spain and Portugal), which sort of formed the second front against Islamic realms, the Knights Hospitaller formed their own self-governing units usually commanded by members of native ethnicity.

As we can comprehend from the list of these regions, the realms of Germany proper (‘Holy Roman Empire’) are conspicuously missing. That is because the free populace of these areas rather preferred the native Teutonic Order – since the Hospitallers were perceived as being too ‘French’ and also close to the Papacy (at a time when German emperors were at loggerheads with the Vatican).

In any case, it should be noted that by the latter half of the 13th century, membership to the Knights Hospitallers was restricted, with recruitment drives mostly focused on young men who came from noble and knightly ranks. This perhaps had to do with the practical reason involving large financial donations brought forth by the rich recruits upon their initiation into the religious order.

The Motivation To Join Ranks

Now considering the monastic and relatively strict (and dangerous) lifestyle of the military order members like Knights Hospitaller, the question can be raised – why did free men join their ranks in the first place? The answer to that is, instead of viewing it through the lens of our modern-day sensibility, one should understand the societal and economic structure of feudal Europe in the 12th century.

To that end, the ordinary Hospitaller brethren (non-knightly members) had varying reasons to join the reclusive ranks. Usually hailing from somewhat poorer sections of society, many joined to simply provide themselves with timely meals on a daily basis, while others looked on it as career opportunities where they could achieve a military rank (and the perks and rations that went along with it).

A few others, the most desperate (and illiterate ones) simply took the gamble to be ‘martyrs’ – pertaining to a glorious death on the battlefield against the ‘infidels’. According to their beliefs, aided by propaganda, this would release them from their uncertain lives (that in the middle ages were sometimes cut short by diseases or starvation), and gain them ‘direct access’ to heaven.

And as for the higher ranking Hospitaller members, in the initial years, many of these knights possibly wanted to escape their personal tragedies over at home, like the death of their loved ones. Others joined the Order as penance for their presumed sins, while some of the knights also seriously believed in the ‘core’ cause of the Hospitallers and Templars – to protect Christian pilgrims in the Holy Land and wage war against the ‘non-believers’.

One could also not discount the few wealthy crusading knights who tended to mix their sense of adventure and piety and enthusiastically embarked upon the Holy Land. And in spite of all these hypothetical motivations, one should understand that medieval Christian military orders always tended the face shortage of manpower, especially the fighting men.

This led to some stricter measures advocated by the Knights Hospitaller who didn’t permit any member to voluntarily leave their order once they were initiated (though there were rare episodes where rich members illegally bought their way out).

The Knights of Knights Hospitaller?

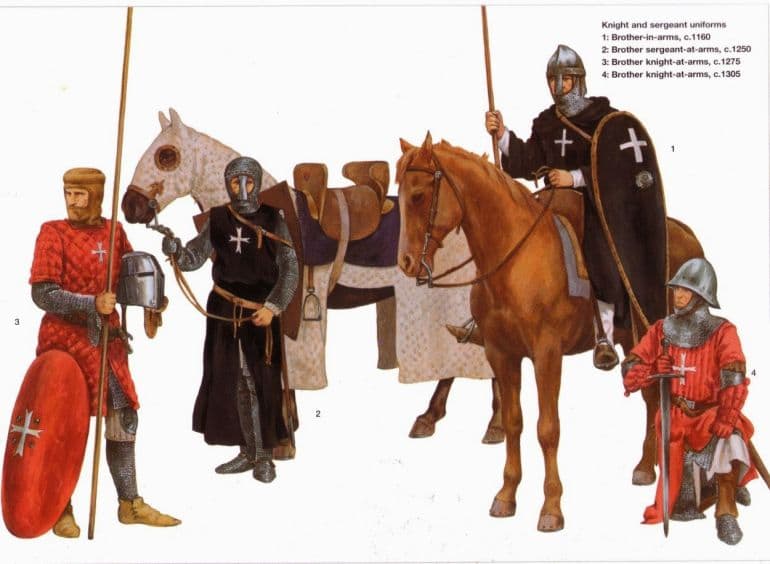

As we fleetingly mentioned in the last entry, not all members of the Knights Hospitallers were knights (thus somewhat mirroring the structure of the Knights Templar and Teutonic Order). And while in the earlier years (circa 12th century AD), all Hospitallers were equitably called brothers, the 13th century and its more stringent feudal setup also reflected in the changing hierarchy of the orders.

Thus the core fighting force of the Hospitallers was mainly divided into the knights and the brother-sergeants-at-arms (also known as the caravaniers). These caravaniers were highly effective soldiers yet were perceived as having a lower status than the knights.

The non-military counterparts to the middle-ranked caravaniers were the brother-sergeants-at-service who formed the administrative and clerical backbone of the Knights Hospitaller. And finally, the largest (yet with the lowest status) group within the Hospitallers pertained to the simple sergeants who carried out the menial tasks.

There were also supporting groups associated with the Hospitallers, including the donats – rich noblemen who financed their own military expeditions to the Holy Land and were inducted into the order ranks as sort of honorary members and the confraters – well-off nobles tasked with defending Hospitaller convents and residences but not counted among the brethren of the order.

The Alleged ‘Ancient’ Legacy

Now while as organizations the Crusader military orders like Knights Hospitaller and Knights Templar were clearly founded during the medieval times, the propaganda machine (or at least its medieval equivalent) presented them as rather ‘ancient’ institutions that always had their millennium-old roots in the vicinity of the perceived Holy Land.

In the case of the Templars, their very (official) name Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon’ (or Pauperes commilitones Christi Templique Salomonici in Latin) referred to the ancient and mystical Temple of Solomon. As for the Hospitallers, there were some legends that suggested how the order existed during the time of the Apostles and the reign of the first Roman Emperor Augustus.

Other fables and related anecdotes put the brotherhood even further back in time, with some claiming how Judah Maccabee (Yehudah ha-Makabi in Hebrew), the Jewish priest who lead the successful Maccabean revolt against the Seleucids (circa 167–160 BC), was a popular patron of the hospital in Jerusalem. Other exalted figures in Christianity, like John the Baptist and Jesus Christ, were mentioned as visitors to the establishment in the following centuries.

The Religious Enthusiasm And Discipline

Of course beyond abstract ancient connections, the Christian military orders also focused on the sacred relics that directly inspired the martial psyche of many a medieval Crusader. One pertinent example in the case of the Knights Hospitallers would relate to a medieval gilded bronze reliquary exquisite crafted in the shape of a bishop’s miter. It was found to contain bits of relics, including that of the True Cross and saints (originally discovered in 1893).

Physical artifacts were complemented by poetry and hymns that sang the virtues of declaring war on the summa culpabilis – the ‘blameworthy’ of people. However, religious motivations aside, the success of military orders like Templars and Hospitallers on battlefields directly pertained to their ingrained discipline.

Simply put, while bouts of fanaticism were showcased (by both sides – Christians and Muslims during the Crusades), it was ultimately the sense of better military dedication and doughtiness that carried the day.

Pertaining to the latter qualities, the Knights Hospitaller were renowned in Christian circles (and infamous in Muslim circles) for their uncompromising ideals, with directives like no Hospitaller castle could surrender, regardless of the number of defending forces, without the prior knowledge of the Chapter Master.

Relating to one such scenario, when the Knights Hospitaller castellan (a rank that entailed the commander of the order’s most important strategic castles) of the Krak des Chevaliers died circa 1170 AD, Ali Ibn al-Athir, the contemporary Arab (or Kurdish) historian wrote in a succinct manner (as referenced in Knights Hospitaller 1100-1306 By David Nicolle) – ‘[he had been] a man through his bravery, occupied an eminent position and who was like a bone stuck in the throats of Muslims’.

The ‘Simple’ Armor

One of the cornerstones of the Knights Hospitaller belief system centered on simplicity, and this was mirrored by their guarnement or set of arms and armor. In essence, as opposed to the knightly ranks of Europe and even the Outremer, the Hospitallers (like their Templar contemporaries) tended to avoid decorative elements on their armor.

But that is not to say that their armor was of inferior quality; on the contrary, the Hospitaller knights were more likely to import and thus pay a considerable sum for their heavier armor and protective gear from Europe (as opposed to the local Crusader States). To that end, many of the Order brethren and agents, dressed in their unassuming garb, were specifically sent to Europe (by chapters) to not only source better quality armor but also horses and other complementary military equipment.

In terms of actual gear, the armor system for the Hospitallers knights translated to a heavy mail hauberk that was covered by their characteristic black robe and usually accompanied by a quilted aketon or gambeson underneath mail. The protective extensions usually entailed a mail coif (fort et turcoise) for the head, cuisses for the thighs, and manicle de fer (or mail mittens) for the hands.

However, it should be noted that even high-ranking knights and caravaniers sometimes ditched their heavy mail hauberk during the summers, especially during brief forays and raids. Instead, they opted for the aforementioned gambesons or panceria (light mail armor). Some of the lower-ranked Hospitaller brothers, especially on the Iberian front, probably also preferred coirasses or leather armor.

The Various Arms

In the second half of the 13th century, it is estimated that the Knights Hospitaller had to spend 2,000 silver deniers to fully equip a knight, while a mounted caravanier (brother sergeant) was equipped with the cost of 1,500 deniers (at the turn of the 14th century). This included the cost of both armor and arms, with good quality swords alone costing around 50 deniers, while well-crafted helmets accounted for over 30 deniers.

Nevertheless, swords were perceived as very important weapons by medieval European knights – partly because of their forms that insinuated Christian symbolism. Simply put, the typical sword resembled the cruciform with the crossguard cutting a right angle across the grip which extends into the blade. Such imagery must have played its psychological role in bolstering the morale of many spiritual Hospitaller knights and brothers.

However, on the practical level, the most effective weapon for the Hospitaller knight probably pertained to the cavalry lance (usually 10 ft in length), with its sturdy shaft usually made from hardy spruce. The supporting infantry brethren made use of a variety of other weapons, including axes, maces (grudgingly adopted from their Muslim foes), and guisarmes (long-hafted variants of axes).

The Charge of the Knights Hospitaller

The ‘tour de force’ of the Knights Hospitallers, like their Templar contemporaries, arguably related to the capacity for fighting and organizational skills during the early medieval Crusades. But oddly enough, there were no specific instructions dedicated to martial training and pursuits, at least when it came to the Rule of the Templars (a codified statute approved by the Pope himself).

This was probably because the warrior-brothers who joined the Knights Hospitaller and Knights Templar ranks were already expected to have some experience in fighting and tactics – be it in horse-riding or wielding swords, couched lances, and spears from horseback (or dismounted positions).

Interestingly, some regulations also allude to the use of rather ‘exotic’ non-knightly weapons such as crossbows – that were fired from both horseback and on foot. Furthermore, the Hospitallers, like Templars, also employed mercenaries like the famed Turcopoles (derived from the Greek: τουρκόπουλοι, meaning ‘sons of Turks’), who were mainly lightly armed cavalry and horse-archers usually comprising the local forces of Levant, like the Christianized Seljuqs and the Syrian Eastern Orthodox Christians.

Now beyond training and mercenaries, it was the devastating charge of the knights that brought them renown throughout the Holy Land. From that scope, it can be assumed that the Knights Hospitaller, like Templars, were experts in the tight-packed eschielle (squadron) and charging into their enemies in wedged formations.

And while this maneuver seems simple in theory, it must have required high levels of discipline and organizational skill to actually make it work on a battlefield against a formidable foe. In fact, such degrees of discipline contrast with their secular Western European counterparts, who were more prone to individualistic glory on the battlefield as opposed to dedicated ‘teamwork’.

Interestingly enough, even from the Muslim side, the heavy cavalry of the ‘Franks’ (entailing the knights of both the Crusader States and Christian military orders) was seen as a potent threat on the battlefield – so much so that Muslim warriors (especially archers) were trained to target the horse underneath the knight.

Abu Shama, a 13th-century Islamic scholar (and author of Kitāb al-rawḍatayn fī akhbār al-dawlatayn: al-Nūrīyah wa-al-Ṣalāhīyah – who focused on the history during the reign of Nūr al-Dīn Zangī and Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn), noted after the Battle of Hattin (sourced from Knights Hospitaller 1100-1306 By David Nicolle) –

A Frankish knight, as long as his horse was in good condition, could not be knocked down. Covered with mail from head to toe, which made him look like a block of iron, the most violent blows make no impression on him. But once his horse was killed, the knight was thrown and taken prisoner. Consequently, though we counted them [Crusader prisoners] by the thousand, there were no horses amongst the spoils whereas the knights were unhurt.

Conclusion – The Practicality of Tactics and Strategy

It can also be hypothesized that the Hospitallers (once again, like the Templars) were more organized simply because of their reactionary measure to counter the superior mobility and tactics of the Muslim armies. Moreover, it should also be noted that many of the knights who joined the Order were already experienced veterans when it came to military careers.

And even on the tactical level, the Crusaders’ armies relied more on coordination between their different contingents and troops types, like the ‘partnership’ system between the heavy cavalry, infantry, and crossbowmen, who planned and progressed together to keep the mounted foes at bay.

This was in contrast to contemporary Western Europe where the nobility and knights paved the tactical outcomes for the supporting armies in many battles. To that end, the heavy cavalry forces of the Crusaders tended to be smaller, and these ‘curtailed’ groups practiced the habit of repeated charging and harassing, as opposed to a grandiosely conceived single massed charge.

Also, in spite of their seemingly rigorous (and at times fanatical) military actions against their foes, the military commanders of the Knights Hospitaller were not delusional about their (precarious) position in the Levant, especially in the late 13th century.

In that regard, Acre – the bastion of the Crusader States, fell in 1291 AD to the ascendant Mamluks. Consequently, the Hospitaller think-tank practically shifted its attention to naval pursuits instead of wasting its severely depleted resources on a land-based military expedition to retake the Holy Land.

This strategic decision paved the way for the Knights Hospitaller to shift their base to ‘offshore’ locations – initially Cyprus and then Rhodes (which further shifted to Malta in the 16th century), thus essentially ensuring their politically autonomous survival till the Napoleonic Era.

The outcome also made the Hospitallers, known in the 14th century as the Knights of Rhodes, a moderately successful naval power that staved off two full-fledged invasions from the Islamic realms (both Mamluks and Ottomans) and acted as the first line of Christian defense against the infamous Barbary pirates.

Featured Image Source: DeadliestFictionWikia

Online References: Medieval Warfare / Britannica / LordsandLadies

Book References: Knights Hospitaller 1100-1306 (By David Nicolle) / The Knights Hospitaller in the Levant, c.1070-1309 (By Jonathan Riley-Smith)

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "Knights Hospitaller: 10 Things You Should Know"