The progression of Western Europe from the proverbial (though misleading) ‘Dark Ages’ to what we know as the medieval feudal times corresponded to a matter of centuries – and a significant part of these ‘reformative’ years was overseen by the Franks.

These originally Germanic people (Latin: Franci or gens Francorum) hailing from the edge of the crumbling Roman Empire, along the Rhine, were instrumental in creating a viable state that thrived over time in military and cultural affairs, thus ensuring in some part the survival and continuation of Western Europe as a collective political power.

In this article, we will focus on the medieval Carolingians, the second major dynasty of the Franks, who at their peak in the 9th century AD (under Charlemagne) ruled an empire that stretched over 1,100,000 square kilometers. Also known as Francia, the empire was larger than both present-day France and Germany combined and as such is often considered as the political predecessor to these modern Western European states.

Contents

- The Precedence of Christianity

- The Cornerstone of Western European Power

- The Age of ‘Significance’

- The ‘Personal’ Warriors

- The Levies

- The Frankish Cavalry

- The Question of Armor

- Francisca, Seax, Spears, and Swords

- The Spanish and Italian Marches

- The ‘Cosmopolitan’ Army of Charlemagne

- The ‘Outside’ Influence

- The Viking Forays

- The Threats On ‘Western’ Water

- Honorable Mention – The Muslim Mercenaries

The Precedence of Christianity

The predecessors of the Carolingian Franks, the Merovingians, while making use of the introduction of Christianity (via the Gallo-Romans) to bolster their political power, generally clung on to their older pagan roots to claim symbolic legitimacy over the Frankish lands.

However, by the first half of the 7th century, in spite of the perceived Merovingian ‘sacredness’, the true political power had passed out of the hands of the kings onto the clasp of the palace mayors. The situation became so dire for the Merovingian rulers that many of their later kings were simply known as rois fainéants (“do-nothing kings”) who were not even expected to have their own armed retainers.

And by the 8th century AD, the royal power was completely wrested away by the Arnulfings, better known as the Carolingians. This was an epoch in Francia defined by the legacy of Charles Martel – the Mayor of the Palace (majordomo). And thus it comes as no surprise that his son Pepin was the first of the mighty Carolingian kings who successfully deposed the last ineffectual, Merovingian dynasty ruler (‘Carolingian’ is derived from Carolus, the Latinized name of Charles Martel).

And interestingly enough, after doing so, he was crowned as the new ruler of the Franks inside the Abbey of St. Denis. In essence, while earlier Merovingians were proclaimed as kings by being raised on a shield (thus harking back to their pagan Germanic origins), Pepin had himself proclaimed the King of the Franks by being anointed with holy oil.

Beyond the political undertone, this momentous act symbolically projected the Carolingian dynasty as the defenders of the Church – thus heralding the precedence of Christianity in Western Europe.

The Cornerstone of Western European Power

Talking of Western Europe, the core political power of the Carolingians was based in the land known as Austrasia, centered on the Meuse, Middle Rhine, and Moselle rivers, comprising parcels of territories from present-day France, Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg.

Suffice it to say, even in our modern context, this area remains the heartland of what we perceive as Western Europe and its economic domain. And historically, the foundation of this legacy was laid down by the Carolingian Franks, not in a single day or year, but over the course of centuries.

One of the incremental changes that signified the progression from the proverbial ‘Dark Ages’ to the Medieval period pertained to the conscious use of Late Roman military organizations and the remnant structures by the Franks. Essentially, during the 5th century, the chaotic times required the residents of the urban (and semi-urbanized) areas to defend themselves from the roving bands of intruders, ‘barbarians’, and even robbers.

Centuries later, the Carolingian Franks rather fostered this element of self-defense, wherein well-to-do urban dwellers and rural landlords alike were expected to learn how to fight and defend their strongholds.

Furthermore, the Franks also started to maintain and revive the old Roman military networks that entailed a patchwork of highways, roads, fortifications, and walled cities, thereby revitalizing their burgeoning realm when it came to military affairs. And beyond the martial scope, this translated to better stability in the lands, which led to further economic and expansionist activities.

The Age of ‘Significance’

The revival, however, was only partially bolstered by the remnants of the older Roman military systems. As historian David Nicolle noted, the Carolingian Franks brought forth their own versions of social and political changes, like feudalism and expansionism – fueled by advances in farming techniques and metalworking aptitude.

Moreover, the 8th century Franks were beset on all sides by other powerful cultures, ranging from the Islamic Moors of Spain, the pagan Northerners, to the vestiges of the Eastern Romans and Lombards in Italy, and the Turco and Finno-Ugric tribes on the eastern borders. Unsurprisingly, the Carolingians were influenced by these proximate and foreign power centers, thereby resulting in an exchange and adoption of ideas and styles in the sphere of both military and economic matters.

But the most crucial factor that led to the Frankish political domination of Western Europe (during the period from the 8th to 9th century) arguably relates to their aforementioned alliance with the Papacy. The entente allowed them to be militarily proactive and aggressive, all with an air of legitimacy, as opposed to the defensive battles (of survival) fought by their Merovingian predecessors.

In essence, their military campaigns against the various neighbors, though mostly having the sights on political gains, were often ‘advertised’ as Pope-sanctioned endeavors – where the Frankish emperor (like Charlemagne) played his part as the champion of Christianity.

One pertinent example would relate to the case of Frankish aggression against the Muslim Moors. Focusing on Septimania (an area now corresponding to a part of southern France), the Carolingian Franks resolved to drive out the Muslims.

And while this action may seem like a precursor to the medieval Crusades, the Franks aimed to wrest political control of the region from the Moors (as opposed to religious cleansing) – who were the ‘new’ rulers of a province that had been traditionally under the protection of the Visigoths. Simply put, the Moors replaced the Visigoths as the main political rivals of the Franks in that particular province.

The ‘Personal’ Warriors

Finally coming to the military of the medieval Franks, like many contemporary and ancient armies, the core force of the Carolingians comprised the household troops and their well-armed, professional retinues. These smaller ‘personal’ forces of the palace mayors and the rich nobles and magnates were known as the exercitus (army) or exercitus generalis – thus alluding to their status as the standing army.

Beyond the relatively provincial nature of the exercitus, the royal household troops (along with their band of loyal retainers) of the Carolingian kings and emperors were called the scara (plural – scarae). The elite scarae, though low in numbers, were composed of well-equipped, battle-hardened veterans – many of whom served as armored cavalry contingents under the missi Imperial officers.

In many ways, the scara was also seen as an institution for military officers, wherein many of its members were assigned to command other non-elite units or levies. Interestingly enough, the famed scara of Emperor Charlemagne mainly comprised young yet experienced warriors who were given residential quarters in and around the royal palace. They were possibly divided into three ranks based on seniority – the scholares, the scola, and the milites aulae regiae [referenced in the Age of Charlemagne by David Nicolle].

The Levies

As we mentioned before, most freemen of the Carolingian society were expected to fight – a tradition borne by centuries of chaos and conflicts after the passing of the Roman Empire. In fact, by the 8th century AD, the brunt of fighting mostly fell upon the shoulders of the Franks living within the historic region of Austrasia – the traditional stronghold of the Carolingian dynasty.

Most of these freemen were liable for military service under the summons (bannum) of the royal herald. In more emergency situations, the Frankish crown called for a type of quick mobilization known as the lantweri – and this could also extend to other people (beyond the Franks themselves) of the Frankish Empire.

Failure to answer the bannum often resulted in a hefty fine known as the heribannum, while not turning up for the lantweri could even result in death sentences. As for the recruitment drive of these levies, the responsibility originally fell on the leudes (loyal officers) employed by the 8th-century Frankish palace mayors. However, by the 9th century, the responsibility was shared by the regional Counts and the bishops.

To that end, the provincial administration (composed of the ecclesiarchy, the royal appointees, and their subordinates) decided upon those who would join the army, and these levies were known as the partants. The partants were supported by the aidants – neighbors who looked after the partants’ families and properties like farms while also covering for the economic output of the ‘absentee’ farmers during the times of war.

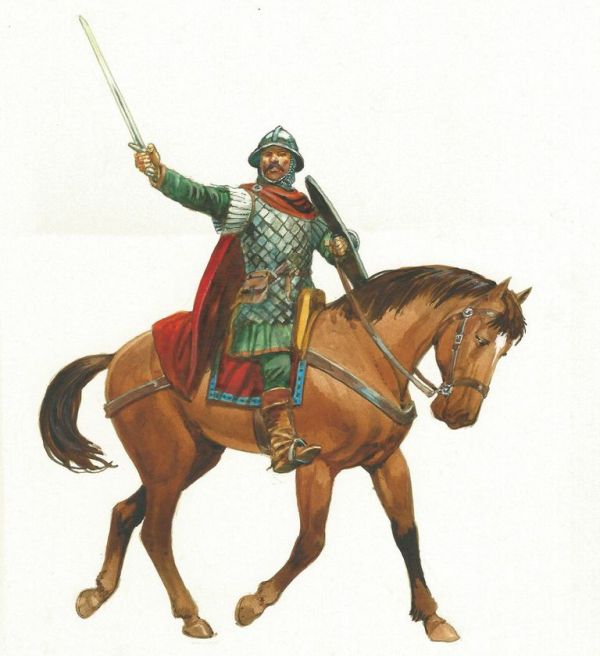

The Frankish Cavalry

The famed Carolingian Frankish cavalry (caballarii) is a somewhat controversial subject in military history. In essence, many 19th-century historians perceived these armored horsemen of the thriving Frankish Empire as the ‘prototypes’ of the later medieval knights. But such an assumption is an over-simplistic one – partly because archaeological evidence has still not yielded stirrups dating from the period of Charlemagne, corresponding to the apical stage of the Franks (i.e., until the 9th century AD).

And stirrups are one of the crucial items needed for making ‘knightly’ charges as they could provide both stability to the rider and absorb (and transfer) the shock of a possible collision during the couched lance charging. In other words, we can certainly put forth the hypothesis that the Frankish cavalry was rarely used for charging and breaking enemy formations.

This naturally raises the question – what was the purpose of these renowned Carolingian cavalrymen? Well, the answer may lie in the tactical advantage of the mobile horsemen, especially in scenarios involving raiding, ambushing, and dealing with isolated formations of foes. Simply put, during combat scenarios, these cavalrymen, instead of mounting frontal charges, could effectively run down pockets of the enemy and gain advantageous strategic coverage of the battlefield.

To that end, the Frankish cavalry was relatively well-armored by the late 8th century, so much so that their brunia body armor often dictated their high status and holdings within the military hierarchy. In fact, the body armor, among all cavalry items, was the most expensive equipment during the Carolingian era, thus reflecting the value of these horsemen. The armor was also complemented by the shield, sword/s (spatha), and (sometimes) lance of the cavalryman.

Finally, it should be noted that the adoption of heavy armor by the Frankish cavalry was made possible by the increasing use of the sturdy Barb horse – with the accessibility to this North African breed made easier through the Moor-controlled Iberian peninsula. And over time, by the mid-9th century, the Franks gradually began to make use of stirrups, possibly inspired by their eastern neighbors – the Avars and the Magyars, as opposed to the Arabs of Spain.

This essentially transformed the Carolingian cavalry (who formed a significant part of the Frankish army) into the typical heavy cavalry of Western Europe. And while still preceding the knights and their couched lance tactics by over a century, these heavy cavalrymen formed the famed scara contingents, which were further divided into the tight-packed cunei – composed of 50 to 100 horsemen.

The Question of Armor

The question once again boils down to this – what kind of armor did the heavy Carolingian horsemen (like Charlemagne’s scola) wear to battle? To be more specific, the query pertains to their brunia armor. According to some academics, this type of body armor possibly entailed scales (made of iron or even bronze) that were stitched on leather or cloth, thus resulting in a relatively flexible yet sturdy hauberk.

Similar types of armor (and their lamellar counterparts) were still used by the contemporary Eastern Romans (Byzantine Empire), Avars, and Arab Moors – which suggests the influence of other cultures on the medieval Franks. In essence, it alludes to the scenario where Western Europe was open (as opposed to segregated) in terms of the adoption of military ideas, along with flourishing trade networks and diplomatic missions.

However, on the armor front, it should be noted that mail was also a popular form of protection during the time of Charlemagne and his successors. This could have meant that some of the heavy Frankish cavalrymen (especially by the 10th century AD) possibly wore mail shirts reinforced with horned plates.

Similarly, in the case of their head protection, the Carolingian horsemen may have used helmets that fused the design of earlier Roman cassis and the later two-piece ‘French’ styles, which resulted in a typically extended rear – though there is no archaeological evidence of such helmets. On the other hand, there are pieces of evidence of simpler one-piece helmets from the proximate period.

In any case, one thing is for sure – only the most elite and rich warriors of the Franks could afford full body armor that included the brunia and arm-and-leg defenses. For example, as referenced in the Age of Charlemagne (by David Nicolle), the total cost of armor, armaments, and horse of a fully decked out Carolingian cavalryman came at 44 solidi, while the cost of an entire cow came at a mere 3 solidi.

Suffice it to say, many ordinary infantrymen and even some mounted troops had to do without such expensive panoply (and even helmets). They instead relied on simpler modes of protection like leather.

Francisca, Seax, Spears, and Swords

Like most contemporary military cultures, the proverbial ‘go-to’ weapon for the Franks pertained to the ubiquitous spear. Carried by both horsemen and infantrymen, many of these spear specimens had right-angled projections beneath the blade, thus possibly alluding to how they were also used for parrying.

As for the famed francisca throwing-ax, the weapon was already anachronistic by the early medieval (Carolingian) times. 6th-century Greek-Byzantine historian Procopius described the francisca (derived from the Latin word for Frank) of the Franks –

Each man carried a sword and shield and ax. Now the iron head of this weapon was thick and exceedingly sharp on both sides while the wooden handle was very short. And they are accustomed always to throwing these axes at one signal in the first charge and thus shatter the shields of the enemy and kill the men.

Essentially, this meant that the weapon was most effective against mass formations of infantrymen. But by the 9th century, the Carolingians increasingly faced cavalry-based foes, and as such the core of their own army was composed of heavily armored horsemen – thus relegating the need for throwing-ax-based tactics.

Interestingly enough, during this epoch, the francisca was possibly replaced by the seax, a variant of a blade-type weapon that was somewhere between a sword and a knife. These single-edged long knives (also used by the contemporary Anglo-Saxons) varied in sizes, with the smaller ones used as cutlery; while the bigger ones (of 90 cm length), though lacking in pommels, were almost substitutes for swords.

However, beyond seaxes and spears, it was the actual sword that was viewed as the weapon of honor and prestige. To that end, the sword was also the most expensive weapon (by virtue of its cost-intensive manufacturing processes) of the time, thus being mostly available to the very high-ranked warriors of the king’s and noble’s retinue.

It is also interesting to know that the Carolingian Franks did pursue archery skills as a means to confront their horse-mounted counterparts on the eastern front. But as opposed to the powerful steppe-origin composite bows of the Avars and Magyars, the Frankish weapon tended to be of the simple flat-bow design (although in few cases they might have made use of the longbow and the composite bow).

The Spanish and Italian Marches

With the changing military attitude of the Franks (that focused on aggression rather than the defensive actions of their Merovingian predecessors), the defenses of their core lands took a back seat, especially in what is now Eastern France and Western Germany. As Dr. Nicolle mentioned, the eastern side of Germany (like Saxony) contained a nexus of citadels that were connected to old tribal fortifications dating from the ancient Germanic era.

But mirroring the age-old dictum of ‘offense is the best defense’, the defensive systems of the Carolingians in the newly conquered Italian provinces (that were annexed from the eclipsed Lombards) and the Spanish border areas (by the Pyrenees mountains) pertained to the ‘marches’.

These marches comprised frontier provinces that were mostly kept on a state of military high alert. This organizational scope translated to a readily available militia force known as warda, often composed of experienced local warriors. Somewhat akin to the akritai of the Eastern Roman border forts, these warda forces, also consisting of full-time scara elites, were commanded by their local overlords (known as marquises in Spain).

In Italy, the Carolingian Franks, taking advantage of the urban nature of many provinces, also invested in heavy fortifications, some of which (during the initial years) were essentially repurposed monuments and buildings from the Roman era.

The ‘Cosmopolitan’ Army of Charlemagne

Dr. Nicolle talked about the incredible variation in the 9th-century Frankish army (in his book The Age of Charlemagne) when it came to the origins and even ethnicities of different troops. So beyond the scope of eastern Franks (from Austrasia), many of whom formed the core of the military forces, the Carolingian Frankish army was bolstered by Burgundians, Bavarians, Goths, Bretons, Gascons, Aquitainians, and even the Lombards.

Some of these autonomous units retained their native fighting styles. For example, the Bretons were famous for their heavy cavalry armed with javelins and swords, thus forming one of the important mounted warrior units in the non-Frankish contingents (interestingly, Roland was the military governor of the Breton march).

Similarly, the noble retinues of the defeated Lombards, comprising the splendidly armored gasindii horsemen, formed the core of the Carolingian cavalry in Italy, while the Visigoths were recruited for their invaluable horsemanship in the Spanish March.

On the other hand, the Gascons and Aquitainians from the region of southern France were known for their skirmishers (armed with javelins) and city-based levies respectively, while the Germanic Saxons continued to fight on foot with their spears and axes. Added to this multifarious scope was the inclusion of ‘foreign’ troops, including Muslims – about whom we will talk later in the article.

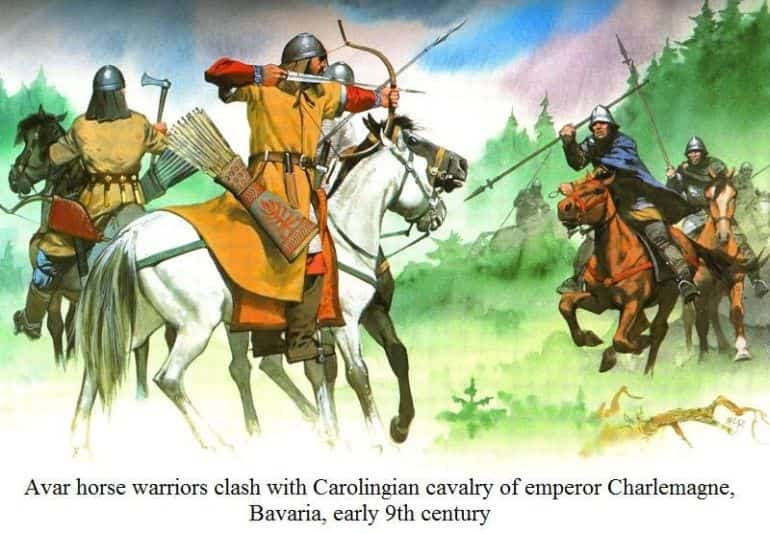

The ‘Outside’ Influence

Now in spite of the various nationalities, allies, and autonomous communities that formed a part of the Frankish Empire, it has been argued that it was their foes – the Avars, who had possibly inspired medieval Franks the most when it came to military matters.

Originally hailing from Central Asia, the Avars were a nomadic people who formed the powerful Avar Khaganate centered in the Pannonian Basin by the 6th century AD. The realm’s wealth and the military were often associated with the fabled Ring – the (possible) fortress capital of the Avars with its impressive defenses comprising earthworks and palisades.

In any case, it might have been their mobile yet well-trained horsemen (furnished with efficient armor and arms borne by advanced metalworking techniques) that influenced the adoption of mass cavalry forces on the part of the Carolingian Franks (while the Merovingians mostly relied on infantrymen).

Similarly, the hard-hitting Avar cavalry archers sort of led to the ‘reactive’ development of archery among some Frankish-employed troops on the eastern front. Furthermore, the Avars may have also influenced the Franks when it came to the endorsement of effective siegecraft in taking down fortified towns and strategic strongholds.

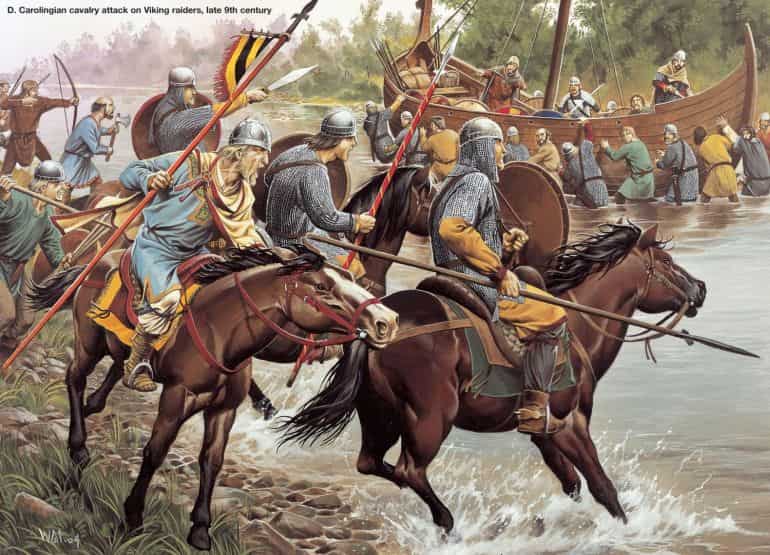

The Viking Forays

Like many a tale in history, after the passing of a powerful ruler (in this case, Charlemagne), the Carolingian empire started to fragment. The precarious situation for the Franks was further exacerbated by the late 9th century when even the nominal authority of the Carolingian emperor was relegated in favor of smaller Frankish kings (and nobles) exerting their limited power over fractured kingdoms, duchies, and provinces – some of whom who even pursued localized military actions against each other.

During such a chaotic state of affairs, the disastrous Norsemen raids came from the northern shores, not only in waves but also directed at various exposed coastal settlements stretched across the deteriorating Frankish state.

From the strategic perspective, these initial Viking forays were spectacularly successful for a simple reason – they were brief raids instead of extensive invasions. Essentially, these raids (aimed at gathering plunder), usually carried by smaller groups of men, offered the Nordic warriors the advantages of surprise and logistical sufficiency.

Moreover, they were known for their ferocity while fighting and tactical aptitude in dealing with a lesser number of foes (entailing skjaldborg formations and precise archery volleys). Added to this, the Vikings were experts in establishing strategically located base camps reinforced with earth and timber defenses.

As for the opposing Franks, their organizational capacity to mount effective (combined) defenses were already eroded due to the political fracturing of the state. Oftentimes, this translated to a situation where the elites fled the raided areas, thus leaving the discontented locals to fend off the motivated Vikings.

Furthermore, as we mentioned before in the article, the Austrasian heartland of the Carolingian power always lacked defensive structures and networks since the very military philosophy of the medieval Franks was geared towards offensive warfare in the late 8th and early 9th centuries.

Of course, over time, the menace of the Vikings was contained in some part by bribing the Norsemen, political maneuvering (like the formation of Normandy), strengthening of forts, and old-fashioned drilling of defensive forces to raise their effectiveness (which included heavy cavalry).

The Threats On ‘Western’ Water

Beyond the menace of the Norsemen, the Carolingian Franks were also challenged by the ‘Saracens’ – a blanket term used for the Muslims, who, in the context of 9th century Western Europe, usually hailed from North Africa and the Moorish-controlled Iberian peninsula (comprising Spain and Portugal).

To that end, by this epoch, the Saracens were already beginning to exert their naval supremacy in the Mediterranean, especially after the decline of the Eastern Romans as a maritime power.

Suffice it to say, this translated to frequent Muslim raids focused along the coasts of southern France and Italy. In fact, as referenced in the Age of Charlemagne by David Nicolle, the sheer magnitude of the Saracen naval ascendancy was manifested when an 11,000-strong Aghlabid army and 73 ships, hailing from Ifriqiya, North Africa, brazenly attacked Rome in circa 846 AD.

They even managed to plunder the old St. Peter’s Basilica but were probably denied access to the main city by the defenders who placed themselves on the sturdy Aurelian Walls.

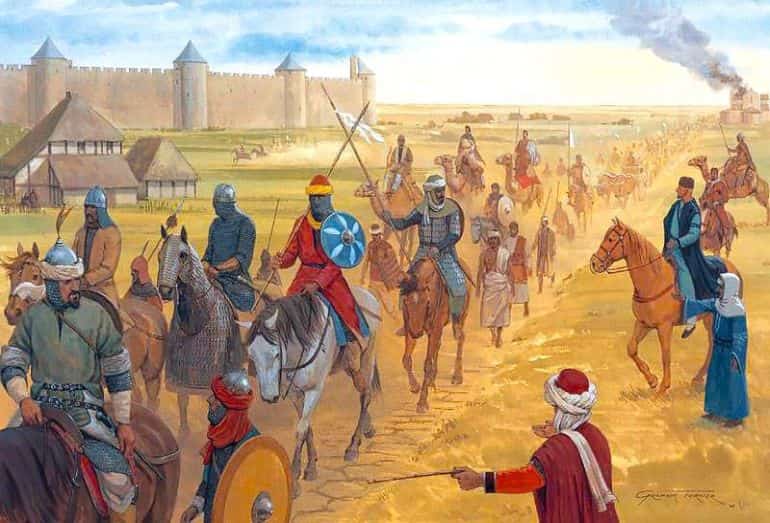

Honorable Mention – The Muslim Mercenaries

One of the unique aspects of the medieval Carolingian Frankish army that mirrored the political (as opposed to the religious) ambition of Charlemagne’s state pertained to its multifarious scope – as discussed earlier. During certain scenarios, it also entailed the employment of Muslim mercenaries by the Franks.

One pertinent example would relate to dissident Arabs and Berbers who mainly served in the Spanish March and even in Provence. Some of these renegade warriors served as cavalry, while others served as infantry and archers (mainly Arabs). Still, fewer had more ‘exotic’ backgrounds with Persian origins, and these men possibly served as relatively well-armored cavalry archers.

Interestingly enough, from the archaeological perspective, in 2016, researchers from the University of Bordeaux and the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research identified three skeletons in an early medieval French grave that may have been of the Islamic faith.

To that end, the discovery of the remains was made in Nimes, near the Mediterranean coast of France, just northeast of the city of Montpelier. Also historically, by the late 9th century, many of the Christian political entities from southern France and Italy actively recruited Muslim mercenaries, not only from the renegade Moors of Iberia, but also from Libya, Sicily (which remained under Muslim rule till the 11th century), and Crete.

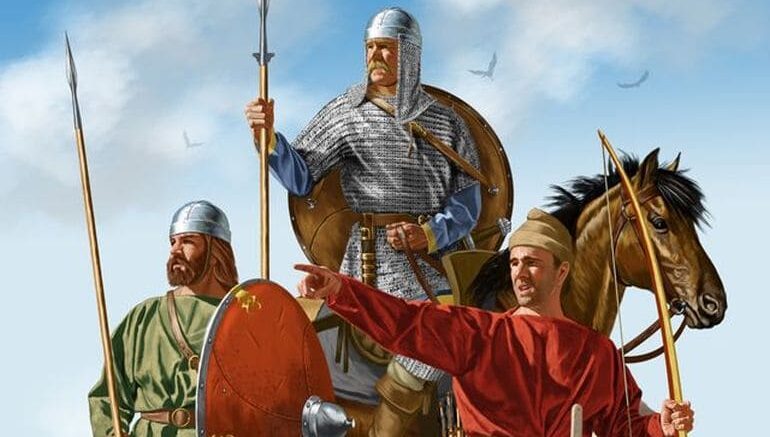

Featured Image: Illustration by Johnny Shumate

Book References: Age of Charlemagne (by David Nicolle) / Carolingian Cavalryman AD 768-987 (by David Nicolle) / The History of the Franks (by Gregory, bishop of Tours)

Online Sources:Britannica / NewAdvent / PenField.edu / WarHistoryNetwork

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "Carolingian Franks: The Military Powerhouse of Early Medieval Europe"