Previously, we covered the reconstruction of Ancient Egyptian faces. The article showcased how academic work in the field, while guided by empirical evidence, is based on educated appraisements and technological advancements (like CT scanning). This time around, we have focused on the facial reconstruction of British people, ranging from a Neolithic dweller of Gibraltar, a Pictish murder victim, to an English king and a Scottish ‘witch’.

Suffice it to say, these recreations – fueled by archaeology, detailed analysis of subjects, and technology, are supposed to be credible estimations of the facial structures at the end of the day (as opposed to precise representations).

Contents

- Calpeia – The First Known Gibraltar Woman (Circa 5400 BC)

- Torbrex Tam – The Oldest Known Resident of Stirling (Circa 2152 – 2021 BC)

- Ava – A Young Woman From the Early Bronze Age (Circa 18th Century BC)

- Pictish Man – (Circa 4th – 7th Century AD)

- Pictish Murder Victim (Circa 5th Century – 7th Century AD)

- Robert the Bruce – The King of Scotland (Reign: 1306 – 1329 AD)

- Richard III – The King of England (Reign:1483 – 1485 AD)

- ‘Lower Class’ Commoner From Dublin (Tudor Era: Circa 15th Century AD)

- Young Scottish Soldier (Circa 1650 AD)

- Scottish Woman Accused of Witchcraft (Early 18th Century)

Calpeia – The First Known Gibraltar Woman (Circa 5400 BC)

A fascinating project from the Gibraltar National Museum culminated in the facial reconstruction of ‘Calpeia’ – the name given to a Gibraltar woman who lived in the Neolithic era, around 7,500 years ago. The name in itself is a celebration of the Classical name of the Rock of Gibraltar.

The incredible endeavor started with the discovery of Calpeia’s remains by archaeologists from the Gibraltar National Museum at a location near Europa Point, way back in 1996. However, it was the recent strides in scientific archaeology that allowed researchers to extract segments of DNA from human remains. Combined with other features, including a 3D-printed version of her skull and real human hair, the forensic team was able to successfully complete the reconstruction in about six months.

Professor Clive Finlayson, the Director of the Museum, explained –

The incredible endeavor started with the discovery of Calpeia’s remains by archaeologists from the Gibraltar National Museum at a location near Europa Point, way back in 1996. However, it was the recent strides in scientific archaeology that allowed researchers to extract segments of DNA from human remains.

Combined with other features, including a 3D-printed version of her skull and real human hair, the forensic team was able to successfully complete the reconstruction in about six months.

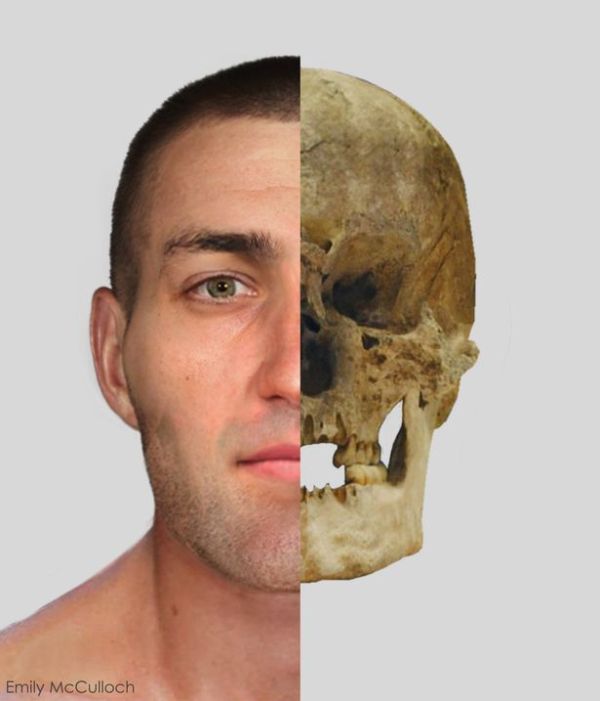

Torbrex Tam – The Oldest Known Resident of Stirling (Circa 2152 – 2021 BC)

Back in 1872, human bones and associated remains were uncovered by workmen within a stone-lined chambered cairn, the oldest structure in Stirling, central Scotland. And while the site is now surrounded by modern residences in Coney Park, the bones hark back to a period of circa 2152 to 2021 BC – as was concluded by a radiocarbon analysis in 2017.

The new findings establish that the remains belonged to a deceased male hailing from the Bronze Age. He is given the moniker of Torbrex Tam and is regarded as the oldest known resident of Stirling. Torbrex in itself refers to the smaller settlement southwest of the main city area.

The recent assessment of Torbrex Tam was also complemented by a facial reconstruction, as a result of a collaborative effort between Stirling archaeologist Dr. Murray Cook, Michael McGinnes of Stirling’s Smith Art Gallery and Museum, and Dundee University forensic art and facial identification graduate Emily McCulloch. Dr. Cook said –

Torbrex Tam died around 2152 to 2021 BC. He is more than 4000 years old. He’s the oldest individual from Stirling and his facial reconstruction is Stirling’s first recorded face. For anyone from Stirling, Tam is their oldest ancestor. I’m sure I’ve seen his face in people around the town.

Ava – A Young Woman From the Early Bronze Age (Circa 18th Century BC)

The site of Achavanich (or Achadh a’ Mhanaich in Gaelic) in the northern tip of Scotland boasts its fair share of mysteries with the famed horseshoe-shaped arrangement composed of an array of stones. But researchers have given the ‘human’ touch to this Bronze Age scope of an enigma, by successfully reconstructing the face of a woman whose remains were discovered at the site back in 1987.

Given the moniker of ‘Ava‘, the young woman was 18-22 years old at the time of their death, while her skeletal remains are dated from around 3,700 years ago. And interestingly, from the archaeological perspective, she was found buried in a pit that was bored inside solid rock.

In regard to the incredible reconstruction project, the work was the brainchild of forensic artist Hew Morrison, a graduate of the University of Dundee. Aided by the comprehensive research project on Ava managed by archaeologist Maya Hoole, Morrison was able to get a lot of details on the history and anthropology of the Bronze Age human specimen.

For example, it is known that Ava probably belonged to the Beaker culture that thrived between 2800-1800 BC in various parts of prehistoric western Europe, ranging from the Late Neolithic to the early Bronze Age period.

From the morphological perspective, the Beaker people tended to exhibit short and round skulls. However, in the case of Ava, the ‘abnormality’ of her skull shape is more pronounced than others, thus suggesting how some sections of the population possibly practiced binding skulls. Other features of her face were gauged from various data parameters, ranging from a chart of modern average tissue depth to an anthropological formula for calculating the depth of the missing lower jaw.

Pictish Man – (Circa 4th – 7th Century AD)

Back in 1986, archaeologists excavating a site at Bridge of Tilt near Blair Atholl, in Scotland, came across a long cist burial. And inside this cist-type tomb (comprising a stone-built compartment), they were able to discover the remains of a 40-year-old man.

Analysis of the skeletal remnants during the time revealed that the man lived during some time between the epoch circa 340 to 615 AD, thus corresponding to the Pictish period of Scotland. In fact, the assessment alluded to the possibility that it was one of the earliest Pict graves ever found by archaeologists.

And after more than 30 years (in 2017), the collaborative effort between GUARD Archaeology in Glasgow and forensic artist Hayley Fisher endowed a visual angle to the decades-old discovery. The result translates to a digital facial reconstruction of the Pictish man who lived around 1,500 years ago. According to lead archaeologist Bob Will –

The actual burial was found in the 1980s and a certain amount of work was done then. But various members of the local community and groups wanted to do more, so they got in touch to take the project forward and one thing they wanted was a facial reconstruction. That is what got the ball rolling on that one.

We then approached Historic Environment Scotland and they gave us a grant as part of the Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology 2017 to help pay for this project, and we’ve been working on it for two years. The facial reconstruction is based on the skull at the time and it has helped us to identify a number of features, such as a strong brow and chin.

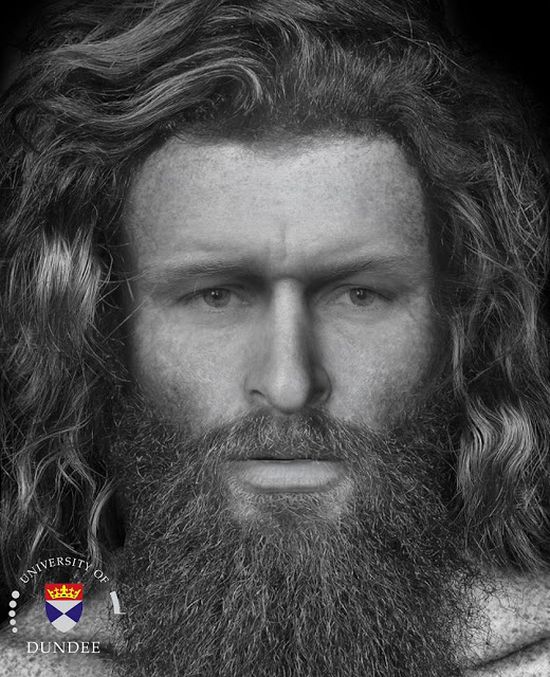

Pictish Murder Victim (Circa 5th Century – 7th Century AD)

The Black Isle, a peninsula (despite its name) in the Scottish Highlands, is home to its fair share of historical mysteries. And one of those came to the fore when archaeologists discovered a skeleton of a man buried in a recess of a cave. The posture of the body suggested a compelling scope, with its cross-legged position and its arms and legs being weighed down by beach stones.

These relatively well-preserved bones were sent to the University of Dundee’s Center for Anatomy and Human Identification (CAHID). The forensic experts determined that the man, hailing from an age around 1400 years ago, was brutally murdered. Additionally, the researchers also managed to reconstruct the facial features of the young Pictish man, thus providing us with a glimpse into the history of the Scottish Highlands during the ‘Dark Ages’.

A team under world-renowned forensic anthropologist Professor Dame Sue Black was able to determine the assortment of rigorous injuries inflicted on the subject. This horrific scope entailed at least five impact points that resulted in the fracturing of the skull and face. As Professor Black explained –

This is a fascinating skeleton in a remarkable state of preservation which has been expertly recovered. From studying his remains we learned a little about his short life but much more about his violent death. As you can see from the facial reconstruction he was a striking young man, but he met a very brutal end, suffering a minimum of five severe injuries to his head.

The first impact was by a circular cross-section implement that broke his teeth on the right side. The second may have been the same implement, used like a fighting stick which broke his jaw on the left. The third resulted in fracturing to the back of his head as he fell from the blow to his jaw with a tremendous force possibly onto a hard object perhaps stone.

The fourth impact was intended to end his life as probably the same weapon was driven through his skull from one side and out the other as he lay on the ground. The fifth was not in keeping with the injuries caused in the other four where a hole, larger than that caused by the previous weapon, was made in the top of the skull.

As for historicity, the radiocarbon dating of the remains indicates that the man lived anywhere between the epoch of 450 – 630 AD, which corresponds to the Pictish period of Scotland. Interestingly enough, the Picts in themselves did not belong to any particular tribe.

Much like the Huns of late antiquity, they were a confederation of different tribes, most of whom dwelt within the confines of northern Scotland from the 3rd to 9th century AD and were probably ethnolinguistically Celtic.

Robert the Bruce – The King of Scotland (Reign: 1306 – 1329 AD)

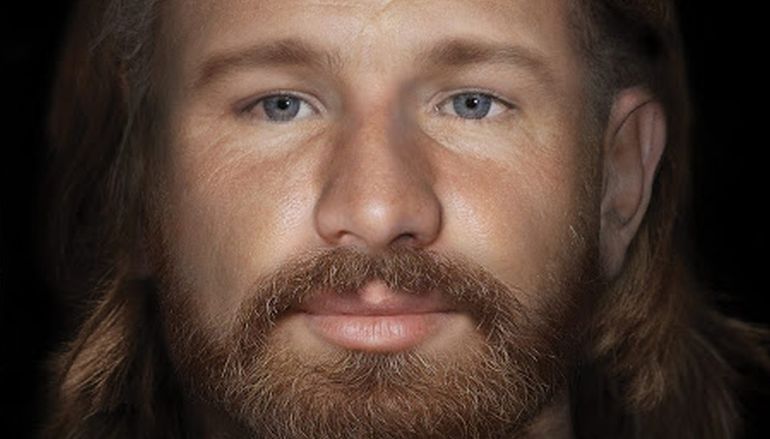

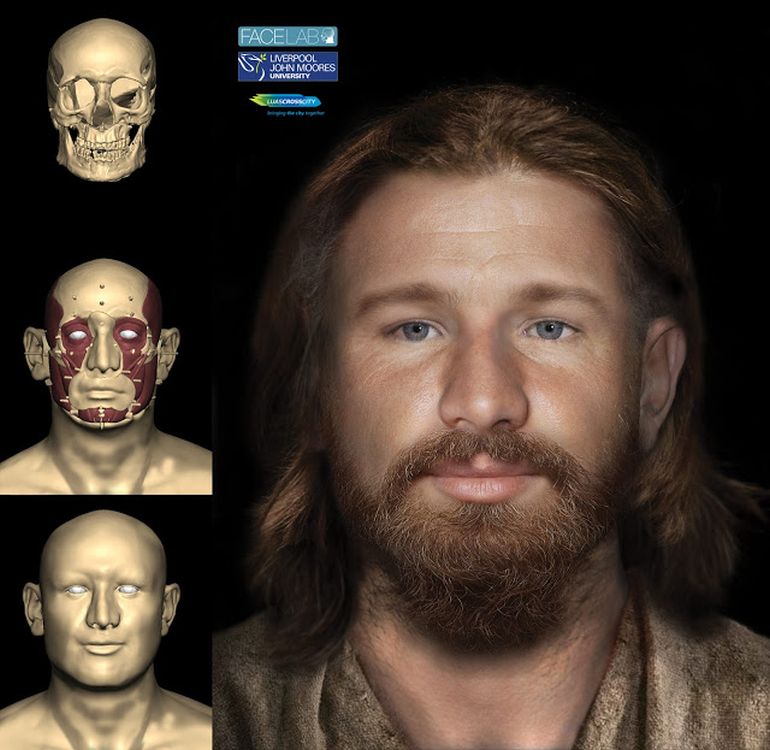

An incredible collaborative effort from the historians from the University of Glasgow and craniofacial experts from Liverpool John Moores University (LJMU) resulted in what might be the credible reconstruction of Robert’s actual face.

The consequent image in question (derived from the cast of a human skull held by the Hunterian Museum) presents a male subject in his prime with heavy-set, robust characteristics, complemented aptly by a muscular neck and a rather stocky frame. In essence, the impressive physique of Robert the Bruce alludes to a protein-rich diet, which would have made him ‘conducive’ to the rigors of brutal medieval fighting and riding.

Now historicity does support such a perspective, with Robert the Bruce (Medieval Gaelic: Roibert a Briuis) often being counted among the great warrior-leaders of his generation, who successfully led Scotland during the First War of Scottish Independence against England, culminating in the pivotal Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 AD and later invasion of northern England.

In fact, Robert was already crowned as the King of Scots in 1306 AD, after which he was engaged in a series of guerrilla warfare against the English crown, thus illustrating the need for physical capacity for the throne contenders in medieval times.

Reverting to the reconstruction in question, the scope of physical strength was ironically also accompanied by frailty, with the skull analysis showing probable signs of leprosy which would have disfigured parts of the face, like the upper jaw and the nose.

Once again bringing history into the mix, scholars have long hypothesized that Robert suffered some ailment (possibly leprosy) that significantly affected the Scottish king’s health in the latter stages of his life. During one particular incident in 1327 AD, it is said that the king was so weak that he could barely move his tongue in Ulster; and only two years later Robert met his demise at the age of 54.

However, as with most historical reconstructions, the experts have admitted that the recreated scope has some percentage of imbued hypothetical data – especially when it comes to the color of Robert’s eyes and hair. As Professor Wilkinson herself stated –

Using the skull cast, we could accurately establish the muscle formation from the positions of the skull bones to determine the shape and structure of the face. But what the reconstruction cannot show is the color of his eyes, his skin tones, and the color of his hair. We produced two versions – one without leprosy and one with a mild representation of leprosy. He may have had leprosy, but if he did it is likely that it did not manifest strongly on his face, as this is not documented.

Richard III – The King of England (Reign:1483 – 1485 AD)

The last king of the House of York and also the last of the Plantagenet dynasty, Richard III’s demise at the climactic Battle of Bosworth Field usually marks the end of the “Middle Ages” in England. And yet, even after his death, the young English monarch had continued to baffle historians, with his remains eluding scholars and researchers for over five centuries.

And it was momentously in 2012 when the University of Leicester identified the skeleton inside a city council car park, which was the site of Greyfriars Priory Church (the final resting place of Richard III that was dissolved in 1538 AD). Coincidentally, the remains of the king were found almost directly underneath a roughly painted ‘R’ on the bitumen, which basically marked a reserved spot inside the car park since the 2000s.

As for the recreation part, it was once again Professor Caroline Wilkinson who was instrumental in completing a forensic facial reconstruction of Richard III based on the 3D mappings of the skull. Interestingly enough, the reconstruction was ‘modified’ a bit in 2015 – with lighter eyes and hair (pictured above), following newer DNA-based evidence deduced by the University of Leicester.

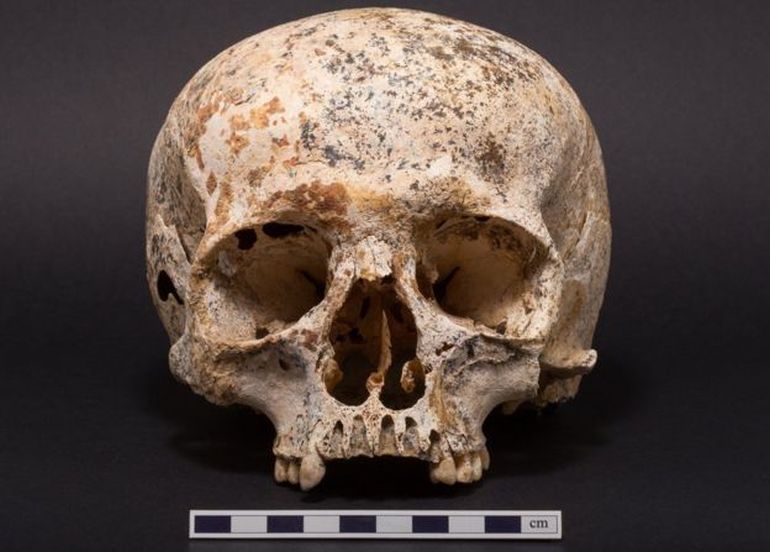

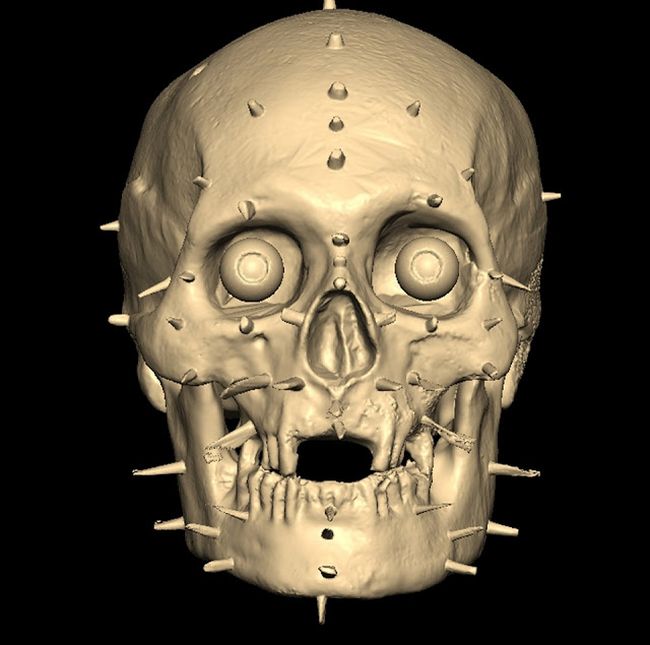

‘Lower Class’ Commoner From Dublin (Tudor Era: Circa 15th Century AD)

Back in July 2014, archaeologists from Rubicon Heritage came across five human burials within the perimeter of a utility trench near the main entrance to Trinity College in Dublin. And while preliminary hypotheses related these remains to the Viking Age or Hiberno-Norse origins (pertaining to the Norse-Gaels from the 9th to 12th centuries), post-excavation analysis led to a completely different result.

Radiocarbon dating of the skeletal remnants placed all of them within the time range of the 15th – 17th centuries, thus corresponding to the Tudor era (1485–1603 AD) – when the conquest of Ireland by the English was underway.

The direct analysis of the skeletons also reveals evidence of childhood malnutrition and heavy manual labor during their lifetimes. In fact, four of these deceased individuals (SK1 and SK3–5) were found to be adolescents, who unfortunately met their demise at the age of only 13-17 years. The fifth burial (SK2) pertained to that of a relatively young adult male (25-25 years) old, and he was chosen as the subject for the facial reconstruction.

Intriguingly enough, by assessment of isotopes (which entails analyzing the isotopes of oxygen and strontium deposited in tooth enamel since childhood), the researchers were able to determine that this man was probably from Dublin, along with subject SK5, while the subject SK1 hailed from either North-East Ireland or Wales/South-West England.

Now coming to the reconstruction itself, the project was handled by the renowned team of Professor Caroline Wilkinson at Face Lab, Liverpool John Moore’s University. According to the Rubicon Heritage –

The first stage of this process was to create a 3D scan of the skull which then formed the basis of the digital reconstruction. Using well-established marker points and specialized software the main facial muscles, soft tissue and skin were layered onto the digitized model of the skull. Analysis of the skeletal remains had already established the age, gender, origin and likely social status of this individual and this information informed the final appearance of the reconstruction.

Other than the direct attributes of the man, the reconstruction specialists also made use of comparative analysis by utilizing contemporary 16th and 17th-century illustrations of Irish people. And while most of these paintings were made for higher-class citizens, the experts could discern some form of analogy that physically defined the Irish male – like the retention of blue eyes and medium brown hair. All of these variant factors played a crucial role in the incredibly life-like reconstruction of a commoner Dubliner from the Tudor era.

Young Scottish Soldier (Circa 1650 AD)

The brutal Battle of Dunbar fought in 1650 AD, as a part of the Third English Civil War, was contested between the Parliamentarian forces commanded by Oliver Cromwell and the Scottish army commanded by King Charles II-loyalist David Leslie. It ended in a short yet decisive Scottish defeat, with possibly over 2,000 deaths on their side, accompanied by around 10,000 captured prisoners.

3,000 of these prisoners were confined in the Durham Cathedral and Castle (many of whom died during their incarceration). And one of these unfortunate souls has now been digitally reconstructed after more than 350 years, thus providing us with a glimpse into the historicity of a 17th-century Scottish soldier.

The project was a collaborative effort between the researchers at Durham University and the experts from Face Lab (based at John Moores University). In fact, the endeavor was fueled by the original discovery of the skull and skeletons of the prisoner (given the moniker of Skeleton 22) that were discovered back in 2013 by Durham University archaeologists.

The first step for the reconstruction entailed the assembling of these skeletal remains for a detailed scan. This digital scan formed the basis of the recreation scope, while the artists additionally used crucial information from the archaeologists about the historical scenario and the age of the Scottish soldier in question here. The experts also added the blue-colored bonnet, brown jacket, and shirt – thus depicting the typical attire of Scottish soldiers of the time.

Now according to previous archaeological analysis of Skeleton 22, researchers came to the conclusion that this male Scottish soldier met his demise at an early age ranging between 18 to 25. And previous to his life as a soldier, the subject hailing from South West Scotland (circa the 1630s), did suffer periods of poor nutrition during childhood. Professor Chris Gerrard, of Durham University’s Department of Archaeology, said –

Analysis of the dental calculus has revealed a lot about the conditions in which this man, known to us only as ‘Skeleton 22’, grew up. This information combined with the digital facial reconstruction gives us a remarkable, and privileged, glimpse into this individual’s past.

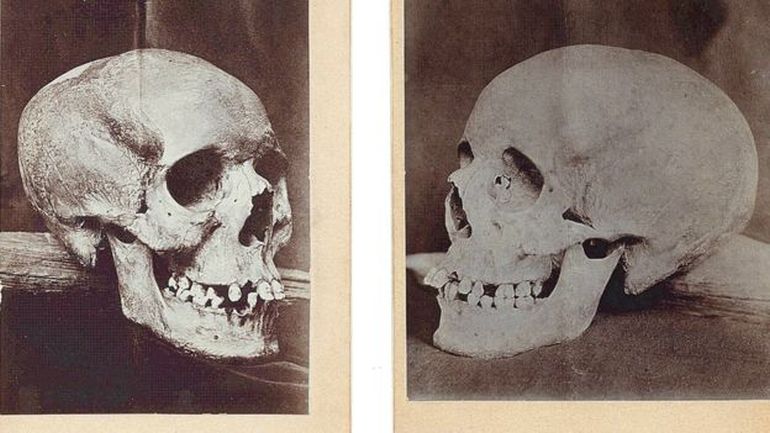

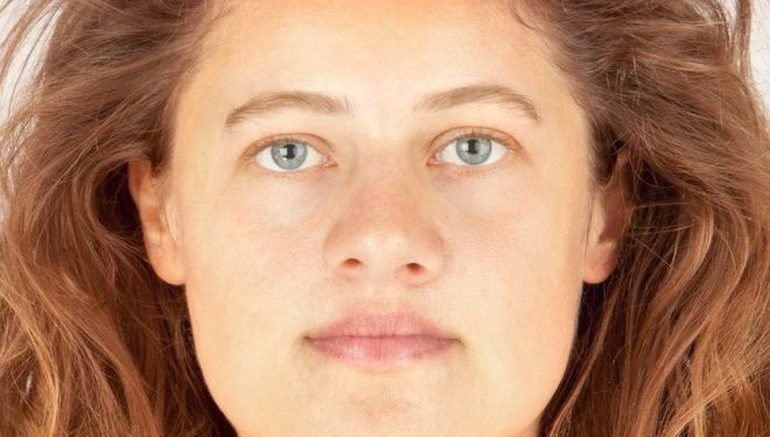

Scottish Woman Accused of Witchcraft (Early 18th Century)

Lilias Adie, from Torryburn, Fife, in Scotland, was accused of witchcraft in 1704 AD after she apparently “confessed” to her dealings with the devil (including having a sexual relationship). However, before she could meet her gruesome fate of being burned alive, she died in the prison itself shortly due to unknown causes, with one hypothesis suggesting suicide. And now, after 313 years, researchers at the University of Dundee have reconstructed the face of the elderly woman for BBC Radio Scotland’s Time Travels program.

The researchers, associated with the university’s Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification (CAHID), believe that their reconstruction is likely to be the only accurate likeness of a Scottish “witch” in existence. The reason is that most of the accused were burned, which rather significantly hampers the chance of recreating such historical visages.

To that end, the period between the 15th and 18th centuries balefully boasts some startling figures when it comes to witch-hunting. According to these epoch-defined numbers, around 40,000 to 60,000 people were tried and executed as witches across both Europe and the American colonies, and possibly 10,000 to 15,000 of them were actually men.

And in line with the anachronistic custom, locals of the area tried to weigh down Ms. Adie’s remains in her grave, possibly as a ‘precaution’ to stop her from haunting them. But it was scientific curiosity that ultimately paved the way for this modern reconstruction project.

To that end, back in the 19th century, some antiquarians decided to dig up her grave for further study and display. In fact, her skull was sent to the St Andrews University Museum, where it was photographed more than 100 years ago. And while her remains were lost by the 20th century, the photographic evidence (pictured above) was salvaged in the archives of the National Library of Scotland.

Suffice it to say, the CAHID forensic experts had to depend on the photographs, as opposed to an actual skull, for their recreation process. To that end, while a conventional reconstruction method takes around 10 to 20 hours to progress from the skull to the muscle structure, to finally the realistic face with its features; in this case, the researchers had to invest almost double that time.

And in addition to the painstaking process, the recreation also brought forth its pangs of poignancy. Dr. Christopher Rynn, who headed the work on the state-of-the-art 3D virtual sculpture, said –

When the reconstruction is up to the skin layer, it’s a bit like meeting somebody and they begin to remind you of people you know, as you’re tweaking the facial expression and adding photographic textures. There was nothing in Lilias’ story that suggested to me that nowadays she would be considered as anything other than a victim of horrible circumstances, so I saw no reason to pull the face into an unpleasant or mean expression and she ended up having quite a kind face, quite naturally.

Be the first to comment on "Reconstruction Of British People – From Neolithic Era Till 18th Century"