Introduction – the Decline of the Viking Raids

In the middle decades of the 11th century, the Vikings had reached the twilight of their raiding and plundering days. After their defeat and humiliation at the hands of King Alfred the Great, the Vikings (or rather Danes) did manage to invade and even conquer much of England, under the leadership of Danish ruler Cnut (or Knut).

In fact, this military action briefly established a ‘Scandinavian Empire’ that encompassed England, Denmark, and Norway in 1027 AD. But all of the lands were soon divided and became independent (Ireland was already free by 1014 AD), while the Anglo-Saxons reasserted their dominance in the English realm by just 1041 AD.

This was a result of an already established trend where disparate Vikings raids were frequently defeated by the professional frontier soldiers in both England and France. Furthermore, the pagan ‘intensity’ of the Vikings had also been dulled by the arrival of Christianity in the core Northmen lands of Denmark and Norway.

However, the proverbial last hurrah for the Norsemen came in the form of the great Viking ruler – Harald Hardrada (Hadrada refers to ‘hard ruler’ or ‘severe’). Ambitiously aiming to restore the North Sea Empire, the ‘Hard Ruler’ claimed his kingship over Norway, Denmark, as well as England. And thus also called the Last Viking King, in this article, we will delve into the fascinating life of Harald Hardrada – a Norse prince who fought in the Middle East, Russia, Norway, and England.

*Note – Most of the history and story of Harald Hardrada is taken from the accounts of The Heimskringla: A History of the Norse Kings, a collection of sagas that was penned in Old Norse by Icelandic poet and historian Snorri Sturluson, in the early 13th century.

Contents

- Introduction – the Decline of the Viking Raids

- The Struggle for the Norwegian Throne

- The Exile and Ascendancy (1031 AD)

- The Path to Adventure, Glory, and Imprisonment (1034 AD)

- The Escape, Riches, and Marriage (1042 AD)

- The Return of the Norwegian King (1046 AD)

- The Last ‘Great Viking’ Invasion of England (1066 AD)

- The End of the Viking Age

The Struggle for the Norwegian Throne

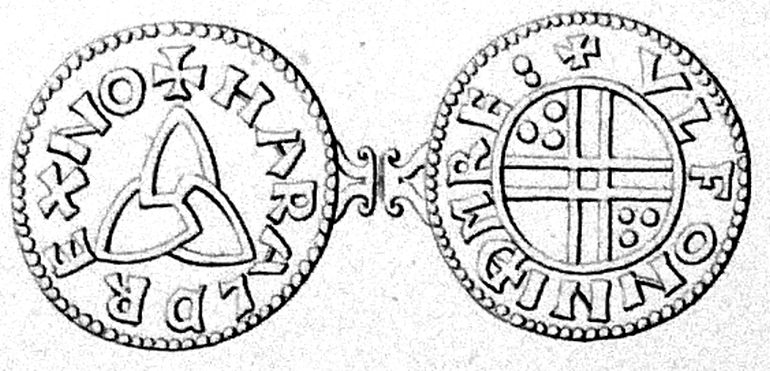

During this nadir period of the Viking Age, Harald Hardrada, also known as Harald Sigurdsson (Old Norse: Haraldr Sigurðarson or Harald Hardråde), was born in Ringerike, Norway, in the year of 1015 AD (or possibly 1016 AD). His father Sigurd Syr was already a strong chieftain (or petty king) from the Uplands of Norway (the rich agricultural regions to the north of Oslo). And as such Harald’s family even claimed descent from the great ruler Harald Fairhair, who was considered the very first king of Norway.

Such claims might have been purported after the actual lifetime of Harald Hardrada, so as to legitimize his actions during the early period of his life. Although it should be noted that Harald’s brother Olaf Haraldsson (or half-brother), also known as Saint Olaf, did establish himself as the nominal Norwegian king by 1015, supported by five petty chieftains.

However, Harald’s family was at loggerheads with the Norwegian crown that had been taken by the renowned (and aforementioned) King Knut of Denmark in 1029 AD. This resulted in disputes between the new king’s supporters and Harald’s family – ultimately leading to the exile of Olaf.

Harald’s brother Olaf Haraldsson made his triumphant return in 1030 AD and then planned for the crown of Norway with his retainers. Harald joined forces with his cousin, with 600 men (hird) from the Uplands. The brothers rendezvoused at the Battle of Stiklestad on 29 July 1030. But they were defeated by a peasant army under the patronage of Danish king Knut. The 35-year-old Olaf died during this encounter and 16-year-old Harald suffered a serious injury.

The Exile and Ascendancy (1031 AD)

Tormented by the grave injury and sidelined by his relative inexperience, there were very few places the teenager could flee to. But in spite of such odds, Harald managed to escape to an inconspicuous remote farm in Eastern Norway. After a month or so of recuperating, he then made his way to the north and boldly crossed the Swedish mountains.

Finally, after a year since the disastrous Battle of Stiklestad, the young Harald Hardrada desperately forced his way into the realm of Kievan Rus (possibly by arriving at the town of Staraya Ladoga or Aldeigjuborg). Rus in itself comprised a loose federation of Slavic trading towns and villages spread across Russia and Ukraine. These settlements were ruled by the Rurik dynasty – who were originally Swedish but had since mixed with the local populace.

Fortunately for Harald, the Rus Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise welcomed the Norseman with open arms – since he recognized the young Scandinavian as the half-brother of Saint Olaf (who previously took refuge in Kievan Rus, during his exile). Moreover, not long after Harald arrived in Rus, Yaroslav also employed the young man as one of his military captains – possibly due to the unorganized state of the Kievan Rus army in the early 11th century.

Under this newly acquired title, Harald Hardrada made a name for himself and his company, by fighting a slew of engagements against enemies, including Poles, Estonian Chudes, and even the nomadic Pechenegs. There are also accounts of how the young Harald tried to court one of Yaroslav’s daughters (probably a woman named Elisiv), albeit unsuccessfully.

The Path to Adventure, Glory, and Imprisonment (1034 AD)

However, in spite of his local renown, Harald Hardrada grew restless with his limited prospects in Kievan Rus. So, by the time he turned 20, he took a brilliant gamble and selected a group of around 500 followers.

This rag-tag band made its way to the regal city of Constantinople (the capital of the Byzantine Empire) which was already known as the fabled Miklagard to the Vikings. The venture paid off, with Harald managing to get himself (and probably his followers) employed as the famed Varangian Guard, the elite bodyguard corp of the Eastern Roman Emperor Michael IV.

And, as was his nature, the ‘Viking’ steadily rose up the ranks by taking part in far-flung campaigns for the Byzantine Empire. According to his skald Þjóðólfr Arnórsson, these conflicts took the still-young Viking to distant places. Thus Harald fought in Asia Minor and Iraq, where he successfully fought off Arab forces and pirates.

After reportedly capturing around eighty Arab strongholds, the Scandinavian even made his way to Jerusalem, to probably oversee a peace agreement made between the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire and the Fatimid Caliphate in 1036 AD. And by 1038 AD, Harald was appointed as one of the (probably nominal) leaders of the expeditionary Roman force that would invade the Emirate of Sicily, which was still under Muslim control.

The now-experienced Varangian Guard fought alongside Norman mercenaries such as William Iron Arm. Their strategies and military acumen allowed the conquering of over four crucial Sicilian towns from Muslim hands. However, the success was short-lived with a combined Norman-Lombard uprising taking place in southern Italy.

The rebels quickly defeated the Eastern Roman forces (on whose side Harald must have played his supporting role) in successive battles, thus wresting control of Sicily from the Romans. So, by 1041 AD, the Varangian Guards were unceremoniously called back to Constantinople.

In that very same year, Harald Hardrada played his important (and vicious) role in putting down a Bulgarian uprising led by Peter Delyan – which supposedly gained Harald the nickname of “Devastator of the Bulgarians” (Bolgara brennir).

However, by the end of 1041, Byzantine politics caught up with the rambunctious Viking, especially after the death of his patron Byzantine Emperor Michael IV. In the ensuing struggle between the new Emperor Michael V and the powerful Empress Zoe, the young Norseman was imprisoned due to charges that vary according to different sources.

These implicating charges range from ‘defrauding the emperor’, to ‘defiling a noble woman’ to ‘murder’. In any case, Harald once again managed to escape from his prison and joined the rebel Varangian Guards against the new Byzantine Emperor. And once again, fortune shined upon him, with Michael V being ultimately defeated and then blinded (a grim task supposedly achieved by Harald himself) – thus allowing freedom for the revolting forces.

The Escape, Riches, and Marriage (1042 AD)

It only took a few months before Harald was once again in disfavor of the crown, this time initiated by the new empress Zoe, who ruled alongside co-emperor Constantine IX. Comprehending his precarious position in Byzantine politics, the Viking decided to leave Constantinople for his homeland in Norway. And, while Harald requested a retirement, the crafty Zoe refused the Varangian Guard. Consequently, Harald Hardrada planned to finally escape the Eastern Roman empire by the Black Sea.

He, along with a few of his followers, chose two ships for the daring escapade, but one of the vessels was sunk by the famed cross-strait iron chains of Constantinople. However, as usual, Harald had luck and presence of mind. So he managed to evade the clutches of the Romans by expertly maneuvering his undamaged ship and then reaching the shores of Kievan Rus in 1042 AD.

It should be noted how the sagas persistently talk about the riches and spoils that Harald had accumulated over the years in the Byzantine court and proximate wars. According to some sources, he was even elevated to Manglabites, a position that consisted of an elite corps that personally guarded the Emperor. In addition to such wealth and titles, Harald is also said to take part in polutasvarf – which might have been an illegal way to plunder the royal treasuries after the death of the Emperor.

Many of his riches and financial documents were sent over the years to Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise, for the purpose of safekeeping. And on returning to the land of Rus, Harald Hardrada once again put forth his proposal to marry Yaroslav’s daughter Elisiv (anglicized as daughter Elizabeth). Impressed by the Viking’s prospects and fortune, Yaroslav decided in favor of giving his daughter’s hand in marriage to the Norseman, in spite of Harald not holding any official title of ‘prince’.

The Return of the Norwegian King (1046 AD)

Finally, the experienced Harald Hardrada decided to return to his homeland via major Kievan cities like Novgorod (Holmgard) and Staraya Ladoga (Aldeigjuborg). From the Ladoga port, he took a ship (supposedly burdened with gold and treasures) and arrived by sea in the town of Sigtuna in Sweden, by 1046 AD. Suffice it to say, forged by his military experience, the ever-confident Harald’s eyes were set on securing the very throne of Norway for himself.

Unfortunately for the expatriate Norseman, much had changed in the political landscape of Norway and Denmark, especially over the years when Harald fought in the Middle Eastern parts of the world.

To that end, both sons of King Knut were dead, and the Norwegian throne once again passed to Saint Olaf’s bloodline, in the hands of Magnus the Good (who was Olaf’s bastard son). What’s more, after Magnus was crowned king, he was regarded as a competent ruler who even managed to defeat a royal pretender named Sweyn Estridsson.

These circumstances put Harald Hardrada in an oddly precarious position, primarily because his claim to the Norwegian throne was superseded by that of Olaf’s successor – a scenario which was even supported by Harald himself in his teenage years. In any case, the boisterous Viking still decided to challenge his nephew, and thus promptly made an alliance with the Swedish king Anund Jacob. Sources also mention how Harald met the other royal claimant Sweyn Estridsson to strike a strategic deal.

Their combined forces made lightning raids along the Danish coast, a tactical ploy that harassed the enemy while also demonstrating the ineffectiveness of Magnus’ retaliation and capacity to protect his subjects.

Troubled by these hit-and-run naval actions, the advisers to the king decided on a political compromise that would allow Harald Hardrada to rule over Norway, while Magnus was to rule over Denmark and also act as the combined realm’s overlord (which made his title higher to that of King Harald Hardrada).

As a result, the two kings made their separate courts and seldom met in person to discuss the affairs of the state. However, in the year 1047 AD, Magnus died without leaving any male heir – possibly from his injuries from a short battle.

Now given his dislike for the exploits and intrusion of Harald Hardrada, Magnus the Good had already named a successor to the throne of Denmark (before his death). And his name was Sweyn Estridsson – the one-time ally of Harald. So after Magnus died, the political turmoil unsurprisingly led to a major confrontation – with both Harald and Sweyn vying for control of the kingdom of Norway and the Danish throne.

And as expected, it was Harald Hardrada who made his first move by hatching a scheme to invade Denmark itself. Quite regrettably, the grand plans didn’t follow through, and the Vikings decided on a series of attrition maneuvers that mainly involved fast raids along the Danish coast (much like during Magnus’s time). These were followed by plundering and localized invasions – but to no avail, as Sweyn remained steadfast in his throne.

And, after 15 long years of constant warfare and chaotic engagements, Harald finally had the opportunity to vanquish Sweyn and his forces at the Battle of Nisa on 9 August 1062 AD. In spite of being outnumbered, the Norseman made use of his Eastern-inspired tactics (involving archery barrages) and defeated the soldiers of Sweyn.

But still, the engagement only resulted in a Pyrrhic victory, with Sweyn managing to escape from the battle with many of his trusted men and ships. And thus years of protracted warfare and their severely increasing costs and casualties finally took a toll on the King of Norway (and his perceived unpopular warmongering).

So, by 1065 AD, the 50-year-old Harald Hardrada decided to make a truce with his longtime adversary Sweyn Estridsson. This freed up both his time and resources for a grander scheme, thus ultimately leading to the last ‘great Viking’ invasion (or Norwegian invasion) of England.

The Last ‘Great Viking’ Invasion of England (1066 AD)

While the concocted truce gave King Harald Hardrada the much-needed breathing space from his desperate military affairs against Denmark, there was also a practical side to this scheme. Coming to the realization that he couldn’t conquer Denmark with his strength and strategies, the enterprising King of Norway turned his attention towards England, a resource-rich realm coveted by many a Viking for more than 250 years.

In many ways, such an action would hark back to the olden days of pillaging and plundering from across the seas – but this time around, the man behind the invasion set his mind to a greater endeavor that could solidify the ‘permanency’ of Norseman presence in the English provinces. In essence, he sought the glory of the very English throne.

But as usual, the political climate in England was far more complex than it had been two centuries ago. To start things off, the English lands were once again united under Anglo-Saxon rule, after the death of King Knut’s sons.

The sagas mention how Hardrada was angered that the crown passed to Anglo-Saxon hands, supposedly because an earlier agreement (between Knut’s son Harthacnut and Magnus) made him the heir to the throne.

And the civic situation for Harald Hardrada was further exacerbated since the newly crowned English king Harold Godwinson (Old English: Harold Godƿinson) was both born and bred in his native lands and thus was immensely popular with the local people.

To counter this potentially ethnic fallout, the Viking readily allied himself with Harold’s brother Tostig Godwinson – who had been previously dispossessed of his earldom of Northumbria by Harold’s predecessor King Edward the Confessor.

King Harald Hardrada was further joined by other chieftains and soldiers in Shetland and Orkney (both under Norwegian rule), namely the Earls of Orkney and probably Malcolm III of Scotland (the King of Scots) who may have furnished Harald’s invasion force with two-thousand Scottish troops.

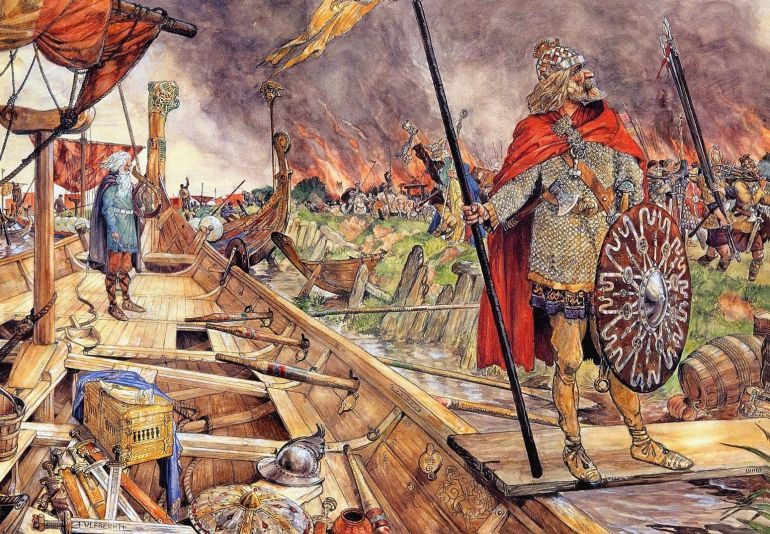

Finally, Harald Hardrada’s Viking invasion force of around 10,000 men made its landing at the River Tees (in northern England) in the year of 1066 AD. His troops went on to plunder the proximate coasts in typical Norsemen fashion. Then he proceeded towards the town of Scarborough and torched it after a brave bout of resistance being offered by the townsfolk.

This brutal action certainly had a psychological effect on the other settlements of Northumbria, most of which went on to surrender to the rampaging Vikings. And, by September, growing wary of these bold Scandinavian incursions, a 5000-strong Anglo-Saxon force from York met head-on with the Vikings at the Battle of Fulford.

But the marshes around the battlefield, along with Harald’s superior deployment, handed the Viking forces their first real victory in a pitched battle – since their invasion had begun. However, more than just results, the battle had serious implications when it came to the strategic outlook of the now-desperate Anglo-Saxons.

In fact, the defeat forced the English King Harold Godwinson himself to march to the front lines. And he did so with a heroic tenacity – when his chosen English army covered a distance of over 190 miles (310 km) in just a week’s time to surprise the Vikings at Stamford Bridge.

The End of the Viking Age

As is often the case with Harald Hardrada’s life, most accounts of the Battle of Stamford Bridge come from King Harald’s Saga penned by Snorri Sturluson. And, what can be salvaged from his descriptions (that also tend to confuse the encounter with the Battle of Hastings) in a realistic manner, pertains to how the Vikings were actually ‘shocked’ to see another English army approaching them, after their hard-won victory in the previous Battle of Fulford.

This might have been because of an earlier agreement that allowed for the exchange of hostages between the two forces. However, the Norsemen saw that instead of struggling hostages, it was a well-equipped 15000-strong English army (supposedly with a “gleam of handsome shields and white coats-of-mail”) approaching them from over the ‘bridge’.

Harald’s predicament was further exacerbated since his Norwegian army was taking it easy – with many already removing their heavy armor, and hence his forces were scattered on both sides of the River Derwent.

So, when the vengeful Harold Godwinson’s army charged through these loose ranks, the rattled Norwegians were scarcely able to make their way across the bridge on the further bank. One celebrated incident mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle relates to a how single Norwegian stood firm on the bridge, thus making a choke point for the overwhelming English forces.

He supposedly even managed to slay 40 of his enemies, before being stabbed through his mail corselet from under the bridge. In any case, this brave defensive measure might have provided the Vikings (on the other end of the bank) with the time to regroup and form their famed skjaldborg (or shield wall).

The advancing English army still managed to hurl itself against the mass of overlapping Vikings’ shields and their shaken bearers. In the consequent engagements of chaotic pushing and shoving (when the Norwegian army was tending to break), Harald Hardrada is said to have invoked his berserkergang (the state of going berserk).

He viciously rushed forth, madly hacking and hewing his way through his foes, until struck by an arrow in his throat. And, thus ended the incredible life of the last ‘great Viking’ – with the Battle of Stamford Bridge marking the conclusion of the Viking Age in 1066 AD.

This is what King Harold Godwinson had to say about his enemy (before the battle) when asked about what was to be Harald’s body (or fate) –

Seven feet of English soil, or as much more as he is taller than other men.

Sources: Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla (excerpts) / TotallyTimelines / Norwegian Encyclopedia /University of Chicago

Be the first to comment on "Harald Hardrada: The Viking Who Fought in Iraq, Russia, and England"