Our popular notions about the Cossacks tended to portray them as the energetic and rambunctious horsemen of the lower steppe from Russia and Ukraine. And while such a perception also holds true in the historical sense, there was more to these ‘horsemen’ that went beyond their boisterous military scope.

To that end, the Cossacks are one of the rare ‘polities’ in Slavic (and Russian) history who formed their ranks based on societal connections rather than ethnicities and origins. These ties were strengthened by the pretenseless mutual appreciation of protecting each other. So without further ado, let us take a gander at the origins, history, and military prowess of the Cossacks, from the 16th to the 19th century.

*Note – In this article, we have focused on the major Cossack groups (as opposed to the numerous later branches and variations of these communities).

Contents

- The ‘Convoluted’ Origins of the Cossack

- The Free Cossacks

- The Russian Cossacks

- The Don Cossacks

- The Protectors of the Steppes

- Napoleon’s Nemesis from the Russian Empire

- The Ukrainian Cossacks

- The Zaporozhian Sich Cossacks

- The Kuban Cossacks

- Horsemanship and Equipment

- The Prowess of the Cossack Army

- The Decline of the Cossacks

The ‘Convoluted’ Origins of the Cossack

The entry in Encyclopedia Britannica puts forth the origin of the word ‘Cossack’ as (being derived from) Turkic kazak, meaning ‘freeman’ or ‘adventurer’. The first recorded use of ‘Cossacks’ was possibly made by the Italian trading colonies along the Black Sea in the 14th century for the bandits and freebooters who operated in the hinterland of southern Russia and Ukraine.

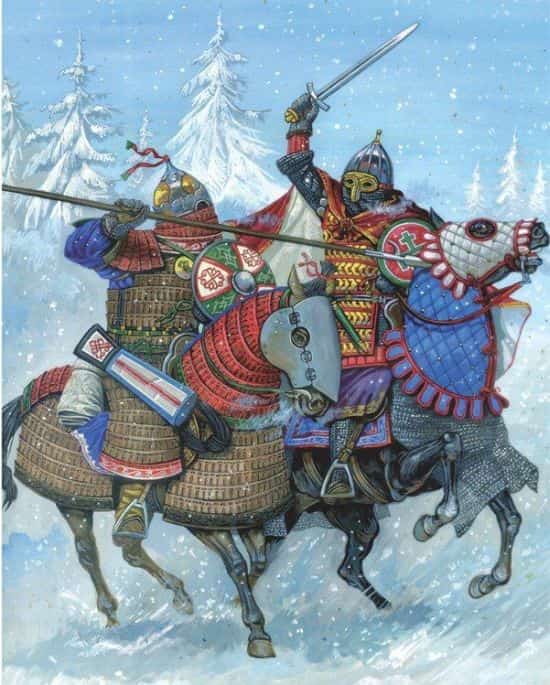

To that end, most historians agree that the first of these Cossacks were probably Tatar raiders (possibly composed of Cuman origins and remnants of the Mongol invasion) who conducted their forays and sorties along the southern Pontic steppe.

Typically, these lightly armed horsemen operated as independent groups, thus alluding to their origins as ‘free adventurers’. However, over time, the term Cossack was also used for the locals who confronted these raiders, possibly with the aid of similar tactics (of fast raids and deft horsemanship). By mid 15th century, many such ‘intermingled’ horsemen were employed by proximate powers like Muscovy and Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

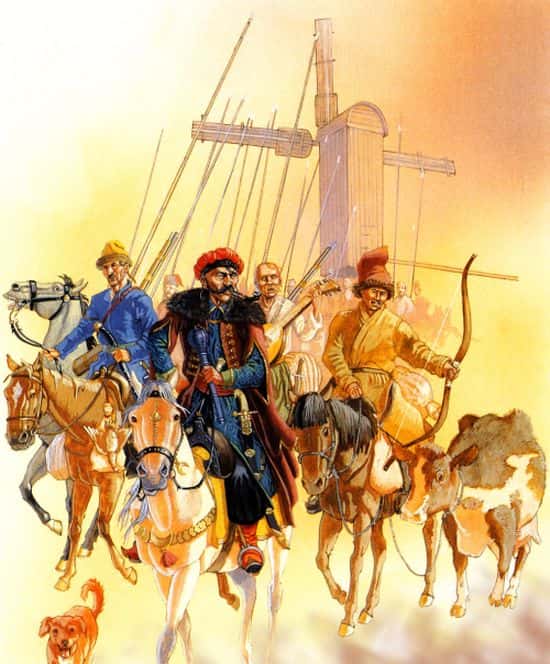

During this time, the (local) Russian and Ukrainian Cossacks gradually began to outnumber their southern Tatar counterparts. These varied groups, although broadly categorized under a singular name (Cossacks), were hired as guides, mercenaries, border patrols, and guardsmen for the rich folks and caravans that crossed the Wild Fields (or wild plains – dikoe pole) – from the Pontic steppe towards the Don and Volga rivers.

The Free Cossacks

According to historian Albert Seaton (as referenced in his book The Cossacks), by the late 15th century – early 16th century, the Cossacks could be broadly divided into the ‘town’ Cossacks and the ‘free’ Cossacks. The former had a semblance of institutions, with most of the ‘town’ Cossacks (gorodovye kazaki) plying their trade as warriors and protectors of the frontier towns. Thus they were often employed (or at least partially aided) by their respective states and princedoms.

One pertinent example would relate to the armed force of Kazan Tatars from the Principality of Ryazan, southeast of Moscow. Like the late Roman urban militia, these men performed their roles as farmer soldiers for their frontier commanders while living with their respective families.

The ‘free’ Cossacks, on the other hand, tended to live and raid beyond the settlements and frontiers. In some seasons, they were temporarily hired as guides and patrols for the caravans treading the dangerous (and often scant) steppe routes. But most of the time, they lived and fought as ‘separate’ people with autonomous status and bare-bones jurisdiction.

By the end of the 15th century, most of these ‘free’ Cossacks (with sometimes intermingled ethnicities) were hosts of fringe elements often divided on the basis of their language. Suffice it to say, based on their insubstantial allegiances, some of these horsemen also took to banditry, thus (in a few scenarios) facing off against their ‘town’ counterparts.

The Russian Cossacks

From the historical perspective, it was the ‘free’ Cossacks who went on to define the legacy of the romanticized Cossack people as we know them today. The first of these ‘real’ Cossacks, as we noted earlier, were expert horsemen, and this expertise was rather borne by necessity – to make fast raids and escape even faster from the garrison towns.

In fact, many of these groups were semi-nomadic in nature. They subsisted by hunting, fishing, trapping, and looting. Simply put, it was their mobility that put them at an advantage in the ‘wildlands’ of the steppe. Consequently, as a cultural extension of Cossack societies, agriculture, and sedentary lifestyle were looked down upon, which made the proximate settlements and realms ‘natural’ enemies of the Cossacks.

Pertaining to the last statement, many contemporary kingdoms, including the Russian Tsardom and the Crimean Khanate, made aggressive overtures against the Cossacks, who by the 1630s, had ballooned into a supranational entity of sorts (although, in a more localized scope), commanding hosts of horsemen and freebooters.

In spite of facing such military actions from the neighboring organized states, the ranks of the Cossacks continued to grow – partly fueled by the steady trickle of Russian refugees. Some of these disfranchised people came all the way from Novgorod, either individually or in families – after escaping from a multitude of situations, like serfdom, perjury, and even downright starvation.

In essence, most of these Russian Cossacks shared their disdain for the Tsarist laws, and as such viewed their life beyond the frontiers with a sense of newfound opportunism. At the same time, the majority of them were welcomed into Cossackdom – whereby their previous crimes were absolved in the equitable society of ‘free-adventurers’.

The Don Cossacks

By the mid-16th century AD, the region by the Don River was inhabited by a host (voiska) of ‘free’ Cossacks who bore the brunt of military actions directed against them by the Tatars as well as the northern Tsardom of Russia (although the latter sometimes provided latent support to these ‘adventurers’ as a bulwark against the roving Tatars).

However, in 1570 AD, in the war against the Crimean Tatars, Tsar Ivan IV Vasilyevich (better known as Ivan the Terrible in the West) made a momentous decision by publicly acknowledging the Cossacks of the Don region. Consequently, under the ‘masked’ support of the Tsardom of Russia (or Moscow Tsardom), these Cossacks organized themselves into capable military units that made regular forays into the Crimean Tatar lands.

Furthermore, these Cossack communities also lend their detachments (to the Tsardom) to fight in distant lands like Livonia and Siberia. Thereby known as the Don Cossacks (or Muscovy Cossacks – as called by their southern Muslim foes), these semi-nomadic people formed a buffer state of sorts. The Don Cossack host established their stronghold at Cherkassk (presently known as Starocherkasskaya) on the right bank of the Don River.

In fact, as historian Albert Seaton mentioned, most of their fortified camps (stanitsi or ‘herds’) were founded along the river banks. Thus the typical Cossack village was not only a strategic outpost for piracy activities (that even took many Cossacks to Black Sea coasts) but also acted as a mini-economic center for fishing.

To that end, in a nod to their egalitarian society, the Don Cossack host held collective ownership of their lands (as opposed to private ownership); wherein every member – as free men, had the equal right to hunting, grazing, and fishing.

However, as per Cossack traditions (in the initial years), farming was remarkably forbidden, with most of the subsidized grain being supplied from the Tsar’s lands. But over time, the Don Cossacks did take part in maintaining salt pans (to salt-preserve their fish) and farms.

As for their relatively forthright form of administration, the local assembly was known as the krug (or rada in Ukrainian) and the stanitsa chief was known as the ataman (derived from the Tatar language). The Don Cossack hosts were at times unflinchingly democratic, with every member of the community (as a free man) having the right to speak at the Krug.

And while the ataman (or rather head ataman) held autocratic powers during times of war, thus fulfilling the role of the commander-in-chief of the Cossacks, he could as easily be deposed (and even punished) by the popular vote at the krug during times of peace. The krug was also responsible for framing the laws of the land that was not only applicable to the Cossacks but also non-Cossack entities who had taken refuge by the Don River.

The Protectors of the Steppes

Now of course like many societies in history, the equitable nature of the Don Cossack laws, including collective ownership, was probably demoted in favor of a hierarchical system by the end of the 17th century – early 18th century. This probably had to do with the class distinction between the ‘old’ Cossacks (i.e., Cossacks who lived in the Don region for generations) and the ‘new’ Cossacks (i.e., newer arrivals from the north).

The former, by this time, had accumulated their fair share of wealth, often complemented by large farmsteads and herds of cattle, while the latter still remained relatively disfranchised and poor. Unsurprisingly, the rich Cossacks tended to have better relations with the emerging Russian Empire. As such, the atamans and leaders were selected from their strata, while the poorer folks still loathed the Tsarist laws and pushed further inland to escape from the Muscovite influence.

Suffice it to say, the Don Cossacks gradually became Russianized, in part because of their language – which was Russian by all accounts. And if we attach a romanticized account, the narrative mostly alludes to how these free horsemen were armed with their characteristic saber and lance.

Roaming the steppes, the ‘Russian’ Cossacks served and fought to protect the emergent Russian state of the Muscovite Tsar from the incursions of the Tatars and their Turkish (Ottoman Empire) overlords.

We should also note how the majority of these autonomous Don Cossack hosts were adherents of the Christian Orthodox faith prescribed before the reforms of Patriarch Nikon of Moscow (circa 1666 AD). Essentially, they were staunch Old Believers who were wary of the ‘metropolitan’ nature of the New Believers based in Moscow.

Napoleon’s Nemesis from the Russian Empire

The ascendancy of the Russian Empire (or Imperial Russia) in the 17th century was partly fueled by the Don Cossacks’ martial aptitude and willingness to fight (under the Tsar). Consequently, the Russian Cossacks participated in far-flung military campaigns, ranging from the Black Sea to the Baltic Sea.

Pertaining to the former, in 1637 AD, the Don Cossacks, along with their Zaporozhian brethren (discussed later in the article) famously captured the mighty Ottoman fortress of Azov on the Don River that strategically guarded the passage to the Black Sea.

In the subsequent centuries, the territory of the Don Cossacks was known as the Voyska Donskogo (Don Voisko Lands). And in the year 1805, befitting their newly-gained renown, they transferred their capital to the larger ‘planned’ city of Novocherkassk (New Cherkassk). Less than a decade later, Napoleon led the French invasion of Russia, with his Grande Armée possibly numbering over 650,000 men.

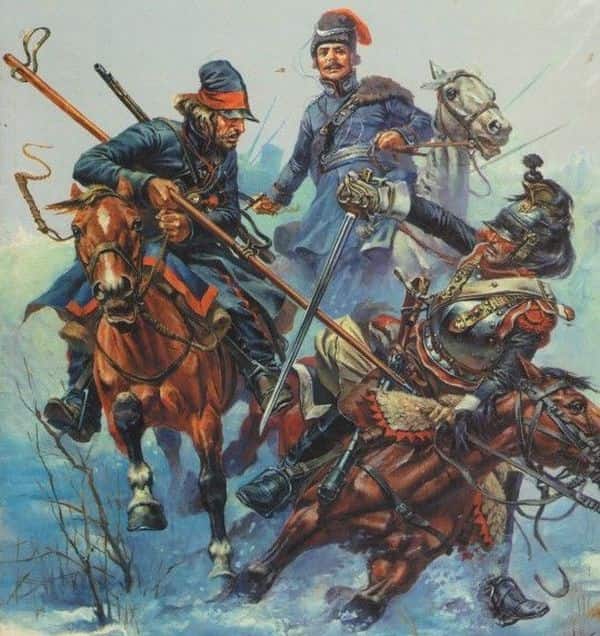

And while the main Imperial Russian army promptly retreated in the face of such a massive invasion force, it was the Don Cossacks who arguably played a pivotal role in not only harassing the French army but also applying the scorched-earth policy. These incessant actions forced the ill-prepared Napoleonic forces to rely on their paltry and dangerously exposed supply lines.

Furthermore, the highly mobile Cossack horsemen were instrumental in mounting raids against their French adversaries at the Battle of Borodino (the largest battle during the Napoleonic Wars) and also covering the retreat of the Russian army to Moscow. After two months, the war of attrition finally took its toll on the Grande Armée, with Napoleon losing over 300,000 of his men, resulting in an unexpected Russian victory.

The Russians, in turn, pushed forth their advantage, with the Cossacks taking part in further actions in the European theater and the momentous capture of Paris in 1814. The impact of these steppe horsemen was reflected by Napoleon’s own words – “Cossacks are the finest light troops among all that exists. If I had them in my army, I would go through all the world with them.”

The Ukrainian Cossacks

The story of the Ukrainian Cossacks almost mirrored the origins of their Russian counterparts. To that end, like the Don host, many of the poorer folks and serfs of the Ukrainian society strove to escape from the clutches of the organized states.

However, in their case, the predicament arguably had a greater magnitude since most of Ukraine was ruled by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Polish aristocracy not only spoke a different language but also professed a different branch of Christianity (the Poles preferred Roman Catholicism while most of the poorer sections of Ukraine were Eastern Orthodox). Their problems were further exacerbated by high taxation and strict socage services demanded by many a pan (Polish landowner).

As historian Albert Seaton discussed, this is where the Ukrainian Cossacks diverged from their Russian counterparts. By the 16th century, the small-time landowners and poor farmers who migrated from the western part of their country to the ‘wildlands’ between Dnieper and Don, sought to create a nationalistic identity of their own.

This idea of an integrated Ukrainian nation was in contrast to that of the Don Cossacks – who perceived themselves as a ‘separate’ people from the Muscovy Russians, in spite of speaking the same language.

Suffice it to say, these newly established Ukrainian Cossacks were seen (by many of their compatriots) as the ‘rightful’ protectors of their nation’s poor and the disfranchised – which further cemented their idealized status among the frontier town folks and farmers.

The Zaporozhian Sich Cossacks

The very term Zaporozhtsi is derived from Zaporizhia (or Zaporozyhe), meaning the ‘land beyond the rapids’. Essentially, the Ukrainian Cossack host that roamed and inhabited the region below the Dnieper rapids was called the Zaporozhian Cossacks. These people made clearings (sich or sech) in swampland around an already existing fort on one of the river islands, thus establishing their first stronghold.

From then onwards, the Zaporozhian Sich Cossacks went to create an autonomous polity of their own that was often viewed as a semi-independent state (by the proximate powers, including the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth) for almost two centuries, from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. For example, as noted from incidents in the 1590s, the Cossacks began to carve their own external policies that were not controlled by the Polish government.

Over time, the Zaporozhian hosts asserted their autonomy and frictions arose between the Polish realm and the Cossacks. These confrontations were mostly driven by the incompatibility of their Orthodox faiths and the Catholicism practiced by the Polish nobility.

Consequently, the lack of expected rights from Poland, coupled with the idealized military status of the Zaporozhian Cossacks among the peasants of Ukraine, culminated in the Khmelnytsky Uprising (or Polish-Cossack War) from 1648-57. The conflict and subsequent Cossack victory resulted in the creation of the Cossack Hetmanate. However, this Cossack state soon became the vassal of the Tsardom of Russia, thereby resulting in the expansion of the Russian sphere of influence in Eastern Europe.

Now as we mentioned earlier, most of these Cossacks were composed of the disfranchised Ukrainians and runaway serfs, originally under Polish rule, who made their way to the southern parts of the Dnieper. In fact, many of the youths from the rural population of the middle Dnieper, allured by the romanticism of ‘free adventurers’, formed the bulk of the recruits for the Zaporozhian Cossacks.

They were joined by Belorussians, along with a smaller number of Moldovans, Serbs, Circassians, Tatars, and even renegade Poles and Germans (as referenced in The Cossacks by Albert Seaton). To that end, by the late 16th century, the situation of ‘power drain’ became so precarious for the Polish kings that the Commonwealth even began to employ and provide economic subsidies to some Ukrainians who were designated as ‘registered Cossacks’ of the Polish army.

As for the nature of the Zaporozhian Sich Cossacks, in many ways, the Dnieper host resembled their Don counterparts, especially when it came to the relatively equitable status of the members – who proudly perceived themselves as free men.

In a broader scope, they were excellent raiders (who made successful forays against their southern Tatar neighbors) and expert fishermen (who also dabbled in piracy in and around the Turkish settlements of the Black Sea). These swaggering Cossack troops were recognized by their clean-shaven heads with the exception of topknots, elegant mustaches, vibrant Tatar attire, and boisterous attitude to go along.

However, as opposed to the Russian Don Cossacks – who mainly settled as families and villages, the Zaporozhian Sich Cossacks maintained their military exclusivity. Simply put, they perceived themselves as a military brotherhood of sorts (that excluded women) – who could conduct lightning forays and plundering expeditions and then escape back to their riverside sich strongholds.

Unsurprisingly, their lifestyle was Spartan with makeshift quarters comprising hastily-built mud barracks. And on occasion, some of these Sich Cossacks did settle in the frontier rural areas (where they were regarded as registered Cossacks) and practiced agriculture.

The Kuban Cossacks

With the decline of the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth and the fall of the Crimean Tatar Khanate, the military ‘independence’ of the Cossacks was rather seen as a threat (as opposed to a buffer) by the ascendant Russian Empire, which had already taken over large parcels of Ukraine by the 19th century.

Furthermore, in the previous century (1775), the Zaporozhian Cossacks were all but destroyed under the directive of Russian Empress Catherine II and General Grigory Potemkin. Only a few of their remnants found refuge in the Danube section under the protection of the Ottoman Sultan.

Interestingly enough, the reason for this quick capitulation was attributed to the degrading military capabilities of the Cossacks – ironically brought forth by their lack of enemies. That is because Russia already annexed Crimea from the Tatars (one of the enemies of the Cossacks) while the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (the other ‘foe’ of the Cossacks) went through a period of severe decline.

Consequently, the Russian government transitioned from treating Cossacks as an autonomous polity to making them a frontier military entity governed by the state. This decision brought forth the birth of the Kuban Cossacks (in 1860). This Kuban Cossack Host was ‘created’ by merging the remaining Zaporozhian Cossacks (by the Dnieper) and units from the Frontier Army (regiments formed of various Cossacks and non-Cossack elements).

Suffice it to say, in spite of their primarily Ukrainian origins, the Kuban Cossacks were thoroughly Russianized in their institutions – so much so that the Russian court even employed an acting ataman (or hetman) who presided over the rada (assembly) and made all the executive decisions pertaining to the host. Subsequently, the military service of such Cossack units was also formalized under the Russian Empire.

Nevertheless, every Kuban Cossack male over 16 years of age was guaranteed his own plot of land (in accordance with the traditions of the Zaporozhian Cossacks). Furthermore, these Cossacks also showcased their military effectiveness in a range of Russian campaigns, including their initial role in the anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army during the Bolshevik Revolution and subsequent Russian Civil War. According to the Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine –

Military training for the Cossacks was very demanding. It included three years of basic training in the stanitsi, four years of active service in the various regiments, four years in the reserve units with annual summer exercises, four years in secondary reserve units with one major exercise during that period, and five years in the general reserve corps, when the Cossacks could be mobilized in an emergency.

The Cossacks provided their own uniforms, swords, and horses. Compared to other Cossack armies, the Kuban host mobilized many units. In 1860 it mustered 22 cavalry regiments, 3 cavalry squadrons, 13 scout (plastun) battalions, and 5 artillery batteries. Later, Kuban Cossacks were often posted in Warsaw and elsewhere in the empire to suppress revolts and serve as special guard units. In 1914 the host comprised 37 cavalry regiments, 22 plastun battalions, 6 artillery batteries, and 47 various other units, for a total of about 90,000 men in active service.

Horsemanship and Equipment

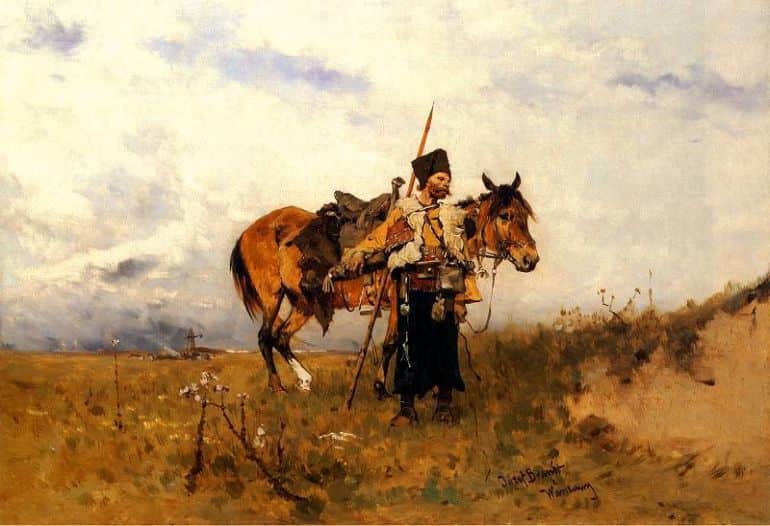

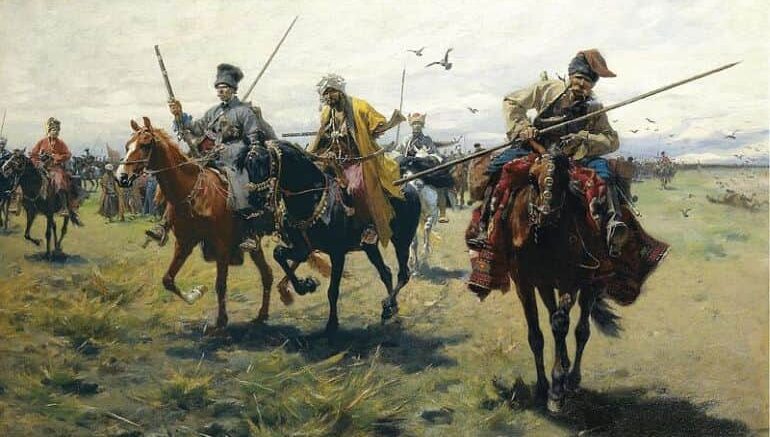

Expert horsemanship was an integral part of the Cossack culture, with their equestrian skills and adeptness influenced (and inspired) by the proximate steppe dwellers like the Tatars, Circassians, and Avars. For example, the Terek Cossacks were known for flaunting the art of dzhigitovka (pictured above) – basically, daredevilry and showmanship on horses possibly learned from their Circassian enemies.

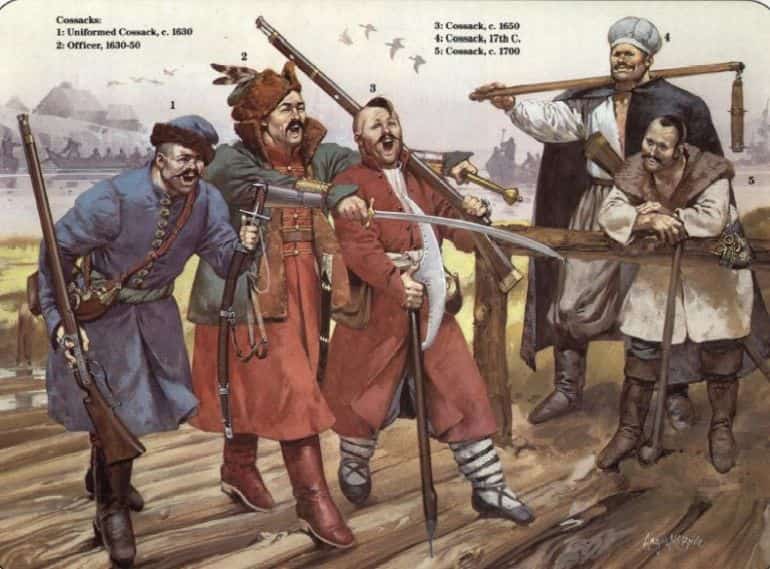

Interestingly enough, the regular Cossacks were also noted for not using spurs (relying on their nagaika whips), thus alluding to their effective control over the relatively passive-natured and smaller steppe horses. As for the Cossack equipment, the early 16th century horsemen between the Dnieper and the Don were typically armed with the lance, saber, and sometimes bow.

By the late 19th century, the colorful Tatar-inspired attire, comprising the sharovary silk pants, gave way to the more ‘ordinary’ all-weather breeches, accompanied by a tunic, standard Russian infantry greatcoat (often complemented by a fur coat), forage cap, and sturdy leather boots. The Cossacks of the later years, however, still retained their typical Caucasian-style papakha (hat made of lamb’s wool) and bashlik hood.

As referenced in The Cossacks by Albert Seaton, the Kuban Cossacks, and their Terek brethren also wore the cherkesska, basically a Circassian-origin tunic with pockets sewn on both sides for carrying cartridges.

Pertaining to the last part, the 19th century Cossack was usually armed with a Berdan rifle (slung across the back) – strikingly, with no bayonet attachments, dragoon-type sword/s, and sometimes lances. The Kuban Cossacks were also known to carry the kinzhal, a Circassian-type dagger.

The Prowess of the Cossack Army

Over the course of two centuries (16th – 18th century), the Zaporozhian Cossacks, with their revived polity below Dnieper rapids, challenged the might of three proximate powers – the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Russian Empire, and the Crimean Khanate. During the same period, the Don Cossacks carved out an autonomous territory for themselves while audaciously carrying out piracy activities on the Turkish cities of the Black Sea coast.

Suffice it to say, the Cossacks at their peak, were a military power to reckon with. This was all the more impressive due to the fact that these societies were borne by the will to survive in the discriminatory world of emerging empires and ‘serfdoms’.

To that end, not only did the Cossacks survive but also thrived – fueled by their mobile fighting tactics and unorthodox yet (relatively) equitable economic system, thus justifying their legacy as the ‘free adventurers’ of the steppe.

The Decline of the Cossacks

As we mentioned before, the Napoleonic Wars rather enhanced the worldwide reputation of the Cossacks. And as forthright and vociferous people themselves, the Cossacks never shied away from the bragging rights reserved for their martial prowess.

However, like many military societies in history, there was the natural decline of these horsemen when it came to sheer military effectiveness – with the nadir generally coinciding with the late 19th to early 20th century (First World War) period.

The reasons for this delve into the realm of complexity, though one of the primary factors relates to how the Cossacks remained relatively anachronistic in their approach to warfare, and thus they were ‘overtaken’ by the better-drilled and equipped German horseman of the same period.

Talking of being drilled, the typical Cossack of the 19th century was rather unkempt and even at times even undisciplined (relying on their natural martial ability instead), which went against the military doctrine of the period. Moreover, in a cruel irony, the ascendancy of the Cossacks in the previous centuries partially paved the way for their downfall.

In that regard, the Russian Empire politically curbed the power of these horsemen and consequently, tended to relegate (in many cases) their officers and detachments to policing and prison duties. Of course, in spite of such impositions, many Cossack regiments did prove their value as regular cavalry divisions and reconnaissance units.

The final slump of the Cossack communities in Russia came in the form of the victory for the Bolshevik Red Army after the Russian Revolution – especially because most of the Cossacks fought for the anti-communist White Army. In acts of reprisals, thousands of Cossacks were killed, exiled, and uprooted by the Soviet Union between the 1920s and 30s. And while there are some records of Soviet Cossacks serving exemplarily in the Second World War, there were also occasions where anti-Soviet Cossack émigrés joined up with German forces.

As for our current era, the Soviet Union momentously passed a law in 1988 that finally allowed for the re-establishment of Cossack hosts, along with the formation of new ones. Since then modern Cossacks (or Cossack-designated units) have taken part in military actions across the borders of the Russian Federation, including the present-day War in Donbas.

Featured Image: Painting by Jozef Brandt (Source – Wikimedia Commons)

Book Reference: The Cossacks (By Albert Seaton)

Online Sources: Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine / Britannica

And in case we have not attributed or misattributed any image, artwork, or photograph, we apologize in advance. Please let us know via the ‘Contact Us’ link, provided both above the top bar and at the bottom bar of the page.

Be the first to comment on "Cossacks: The Warlike Military Settlers of Russia and Ukraine"