Introduction

The famed Praetorian Guards (or cohortes praetoriae) constitute a unique parcel of ancient Roman military history. In many ways, alluding to the proverbial scope of ‘too much power leads to corruption’, the Praetorians started out as a prestigious bodyguard unit loyal to the Roman general and leader.

But over time, with the ever-changing landscape of Roman realpolitik, the Praetorian Guard morphed into an influential political power of its own that played various roles, ranging from the secret police, frontline soldiers, and court conspirators to downright king-slayers (and king-makers). Pertaining to the latter, there were possibly around twelve Roman Emperors who were assassinated or killed by the machinations of the guard.

However, at the same time, we must understand that a handful of these seemingly egregious actions were justified by the political mood of Rome itself. And also, while such political ploys overshadow the historical legacy of the Praetorian Guard, there is no doubt that the Praetorians were the elite of the Roman army (at least for the most part of their existence) who played their crucial military roles in quite a few battles and campaigns.

Contents

- Introduction

- The Republican Origins of Praetorian Guard

- The ‘Watchword’

- The Urban Cohorts and Second Founding

- Castra Praetoria

- The Numbers of Praetorian Guard

- Speculatores Augusti

- The Perks of Praetorian Guard

- The Profile Of A Would-Be Praetorian

- The Armor of Praetorian Guards

- The Misconception Of The Attic Helmet

- The Battle-Ready Praetorians

- The Infamous Auction

- The Fall Of The Praetorian Guard

- Honorable Mention – The ‘Other’ Elite Guards

The Republican Origins of Praetorian Guard

The ‘invention’ of the Praetorian Guard is often attributed to Emperor Augustus. And while part of this scope rings true, the precursors to the organized Praetorian Guard already served generals during the late Republican period.

In fact, the very term ‘Praetorian Guard’ (or Cohors Praetoria) was used during these times to loosely denote the accompanying cohors (group) of praetors (consuls who served as commanders in the field) that mainly consisted of his trusted friends, advisors, and companions – much like the hetairoi of Alexander the Great.

Suffice it to say, over time the members of the cohors were replaced by veteran fighting men who served as elite bodyguards. To that end, both Octavian (who was later proclaimed Emperor Augustus) and his rival Marc Antony fielded their separate Praetorian units in numerous engagements.

In any case, after Octavian secured his final victory over Antony, he resolved to symbolically unite the ‘original’ army of Julius Caesar, thereby combining both his opponent’s and his own troops. Thus the groundwork for the founding of the Praetorian Guard was laid, with the new guard unit – also consisting of veterans from the rival camp, possibly having a total strength of nine cohorts (of 500 men each).

By circa 13 BC, Augustus also reduced the period of service for his Praetorian Guards from 16 to 12 years, which was revised back to 16 years in 5 BC (while ordinary Roman Legionaries had to serve 25 years).

The ‘Watchword’

Interestingly enough, while Augustus inherited probably over 4,500 veteran soldiers after his major victory over Antony, he was wise enough not to flaunt his new-found power during the mercurial times of the early Roman Empire.

So, befitting an astute administrator, the Emperor only kept around three cohorts in Rome itself (according to Suetonius), and these soldiers were billeted around the city instead of being housed in a unified camp. The other cohorts were kept stationed across the major towns of the Italian peninsula.

The command structure of the Praetorian Guard was also changed in 2 BC. While previously each of the cohorts was commanded by a tribune (of equestrian or ‘knightly’ rank), Augustus decided to centralize the command structure by appointing two senior tribunes as the commanders of the overall guard.

These officers were actually responsible for the guarding duties of the Emperor’s residence in Rome (when the ruler was present) and as such even received the watchword directly from the Emperor during the 8th hour of each afternoon.

The Urban Cohorts and Second Founding

During the epoch nearing the end of his reign, Augustus created the Urban Cohorts (Cohortes Urbanae) probably from three existing cohorts of the Praetorian Guard. The move was widely seen as a counter-balance to the rising power of the Praetorian Guard in Rome itself, especially since these new cohorts were commanded by the Urban Prefect (Praefectus Urbi) – a senatorial rank that was above the rank of the Praetorian Prefect.

However, while the Urban Cohorts were trained as a paramilitary force, their main duty was mostly limited to the streets of Rome. Simply put, they acted as variants of the heavy-duty police force, much akin to the specialized riot police of our modern times, who were tasked with controlling crowds and combating riots within the city – jobs that were often critical to maintaining order and political decorum in Rome.

In any case, after the death of Augustus, the Praetorian Guard actually took the field in numerous military encounters aimed at the mutinies in Germany. And while initially, they aided Augustus’ successor Tiberius and his sons, the former emperor’s fears were well-founded, with the guard members (under the command of sole prefect Lucius Aelius Sejanus) playing their role in poisoning Drusus, the heir apparent to the throne after Tiberius.

Sejanus even persuaded Tiberius to construct the Praetorian Camp (Castra Praetoria), in a bid to unify some of the scattered cohorts of the unit. And as Tiberius obliged, the Praetorian Guard adopted the emblem of Scorpio – Tiberius’ birth sign, thus symbolizing their second founding as a military as well as a (latent) political force in Rome.

Castra Praetoria

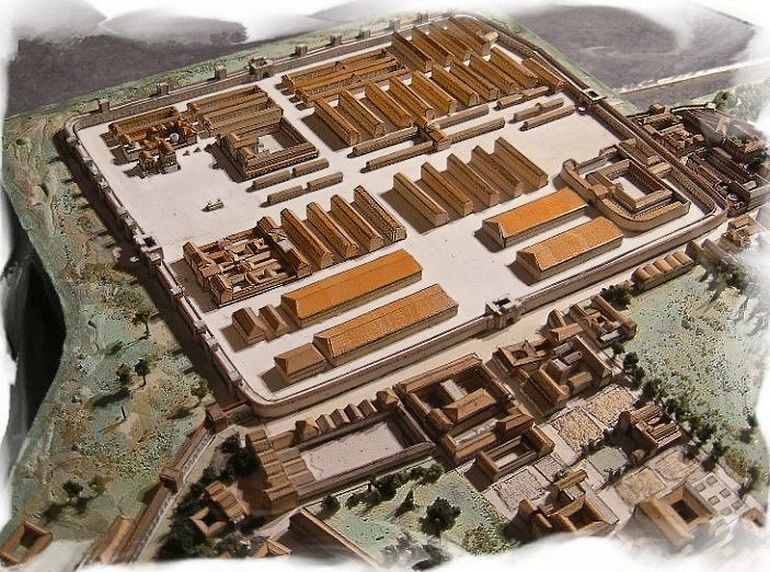

More like a fortress than a camp, the Castra Praetoria (or Praetorian Camp) was constructed in 23 AD by Lucius Aelius Sejanus. Erected just outside the perimeters of Rome, the fort boasted solid masonry walls made of concrete with red-brick facing. It encompassed an area of over 17 hectares (1,440 ft × 1,250 ft) – thus being equivalent to more than 31 American football fields.

And while based on just the area the fort could house around 4,000 troops, archaeologists have revealed the remnants of two-floored barrack structures and extra rooms arrayed around the inside of the walls. These combined spatial elements could have actually accounted for double or triple that number.

The 11.5-ft high solid walls of Castra Praetoria built under the patronage of Tiberius showcased their towers, ramparts, and strategically placed gates. And by the 3rd century AD, Emperor Caracalla increased the height of the walls (circa 238 AD), and they were further improved and reinforced with the addition of battlements by the engineering project of the Aurelian Walls (circa 271 AD) encompassing much of Rome.

And finally, it was Emperor Maxentius who added a flurry of parapets to the massive fort walls (circa 310 AD), but the endeavor came to naught with Constantine being ultimately successful in taking Rome.

The Numbers of Praetorian Guard

There have always been debates surrounding the actual number of soldiers comprising the Praetorian Guard. The predicament of establishing the precise figure is further exacerbated by historical episodes when Roman Emperors increased or decreased the number and even size of the cohorts in the guard. For example, during Augustus’ time, the Praetorian Guard probably had somewhere between 4,500 to 6,000 men, based on the 500-men cohort system.

However, during the short reign of Vitellius (circa 69 AD), the size of individual praetorian cohorts was possibly increased to 1,000 men, much like the first cohort of traditional Roman legions. This might have effectively doubled the number of soldiers serving in the Praetorian Guard, with a figure of around 12,800 troops (some of whom were ironically responsible for the unceremonious death of Vitellius).

Vitellius’ immediate successor Vespasian possibly reduced the numbers to 7,200, and a figure of around 8,000 was probably maintained by the other Emperors until the early 3rd century AD. However, the Crisis of the Third Century once again inflated the strength of the Praetorian Guard to possibly over 15,000 troops, thus mirroring the rising (and often dangerous) political affluence of the elite unit during the Imperial era.

Speculatores Augusti

The elite cavalry arm of the Praetorian Guard (Cohors Praetoria) was known as the speculatores Augusti, and they formed the personal cavalry bodyguard of the Roman Emperor. Now interestingly enough, one of their distinguishing apparels pertained to their special boots caliga speculatoria whose design is now lost to historians.

As for their command structure, these men were under the charge of a separate centurion. However, while they formed their own corps, their names appeared on the ledgers of the cohorts from where they were originally drawn. Unfortunately, we do not know much about the strength of these cavalry bodyguards, which in itself may have varied throughout the timeline of the ancient history of the Roman Empire, much like their Praetorian infantry counterparts.

The Perks of Praetorian Guard

The members of the Praetorian Guard had far more benefits than the regular Roman legionaries when it came to salary, length of service, and the even chance for promotion. For starters, Augustus dictated that the Praetorian Guards be paid twice as much as a legionary of the time; and this pay gap rather increased with the first Roman Emperor’s death in 14 AD.

In fact, a Praetorian was paid thrice as much as a regular legionary with 720 denarii per year – and this form of remuneration was maintained till the 4th century AD. Unsurprisingly, the praemia militare (or discharge bonus) of a Praetorian was also more, being equal to 5,000 denarii, when compared to 3,000 denarii of regular legionaries.

At the same time, the length of service for a Praetorian amounted to 16 years. In comparison, the Urban Cohorts had to serve for 20 years, while the regular Roman legionaries had to serve for 25 years. And even beyond the facade of such official benefits, the Praetorians were often showered with additional monetary gifts and donations (donativum), especially when their political muscle was needed by the Emperors in the later years.

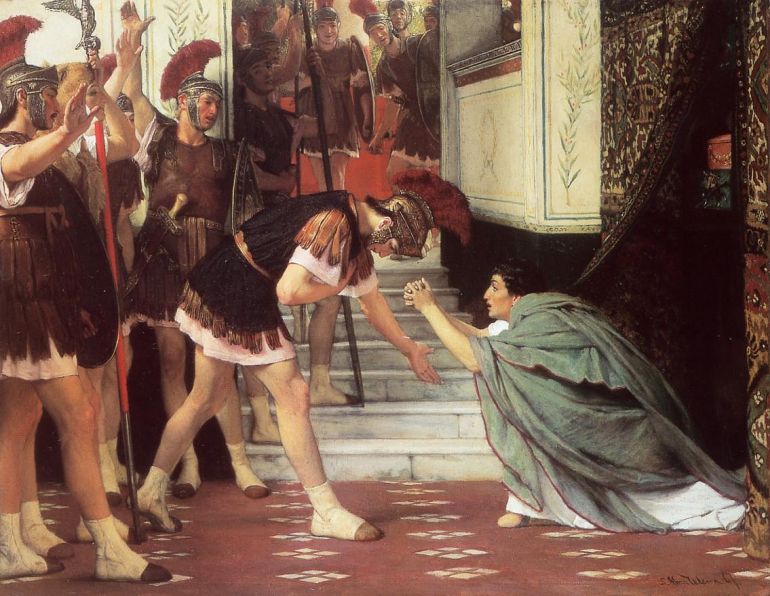

For example, Tiberius made a donation of 1,000 denarii to each Praetorian, as a means to assuage them after the execution of their prefect Sejanus, in 31 AD. Claudius, on his ascension, did one better by buying their loyalty, with a lump-sum payment of 5-years salary at one go.

The favored status enjoyed by the Praetorian Guard in Rome (and proximate Italian provinces) was further pronounced with amendments that allowed its members to legally marry and sire children, while ordinary legionaries were prohibited from the practice at least till the late 2nd century AD.

Furthermore, the Praetorians were more likely to be decorated for their bravery and services, which further relegated their poorer military brethren in favor of discriminatory politics in Rome and Italy.

The Profile Of A Would-Be Praetorian

When it came to regular Roman legionaries, most of the recruits were required to be ‘free’ and had to claim their origo (origin) from a city or at least a town (although most of such documentation was fabricated since recruits from rural areas were preferred due to their perceived hardy nature). On the other hand, to be accepted into the elite Praetorian Guard, the candidate, first and foremost, had to come from a reputable family.

Theoretically, he also had to possess a good character – which was rather ironic when their deeds are evaluated in the later stages of the Roman Empire. Suffice it to say, these basic ‘requirements’ were not enough, and practically the candidate with the most ‘connections’ often had a better chance of being accepted into the guard. Simply put, letters of recommendation and patronage from higher ranks were probably the most important factors that decided the credentials of a potential Praetorian recruit.

As for their origins, Tacitus talked about how the members of the Praetorian Guard were mostly recruited from the core Italian regions of Etruria, Umbria, and Latium, during the 1st century AD. By the late 2nd century AD, the area of recruitment was expanded to northern Italy, Spain, Macedonia, and Noricum (present-day Austria) – still encompassing the rich provinces of the Roman Empire.

However, after the infamous episode of auctioning the throne in 193 AD (which we will talk about later in the article), Emperor Septimus Severus was forced to replace most of these guard members with soldiers from his own Danubian legions. Post this epoch, the politically-motivated move was rather adopted as a tradition, with the majority of Praetorians being recruited from the Romanized Danube region.

The Armor of Praetorian Guards

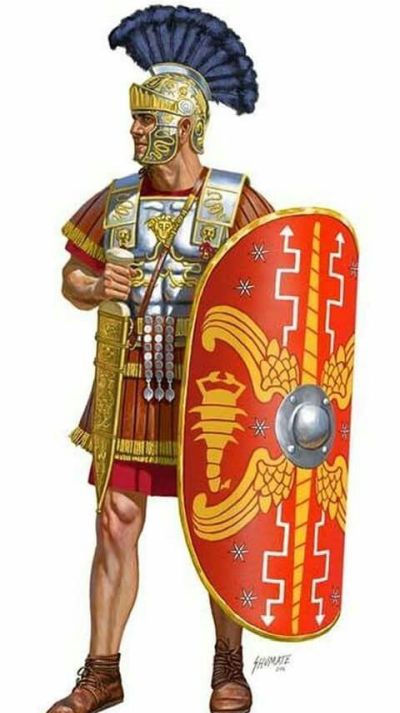

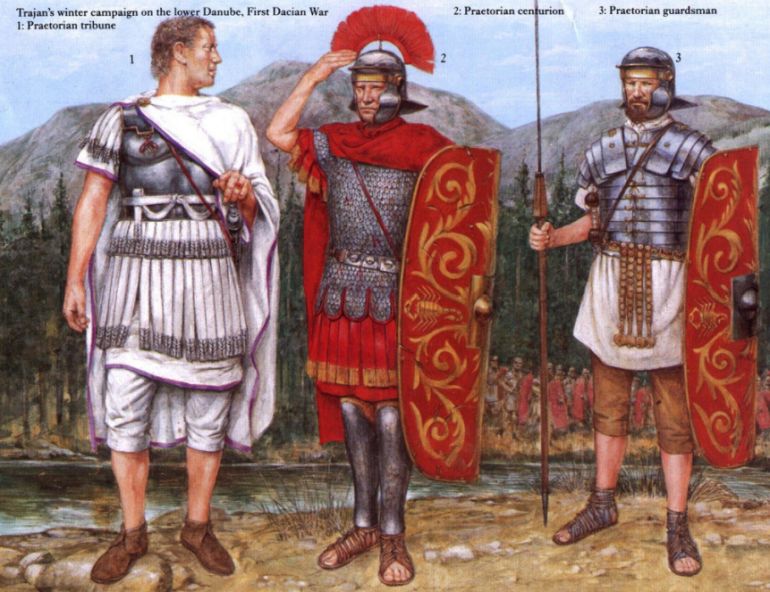

Contrary to our popular notions about the Praetorian Guard, it is highly probable that the Praetorians were armored in a similar fashion to their less-favored legionary brethren. For example, the renowned Trajan’s column depicts both the Praetorians and the regular legionaries in the so-called Lorica Segmentata, while distinguishing the auxiliaries in Lorica Hamata (or chainmail).

Other Roman reliefs, including the Trajanic and Cancellaria, also showcase the Praetorians being dressed in the standard Roman soldier panoply. Now, on the other hand, the Louvre relief does depict two figures wearing the stylized muscled cuirass. But both of them are hypothesized to be portrayals of high-ranking officers, with one of them possibly representing the Praetorian Prefect himself.

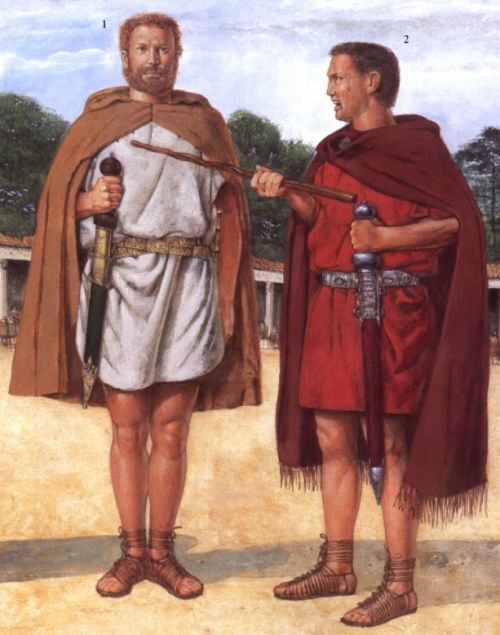

Interestingly enough, beyond campaigning, when it came to actual guarding duties, many of the Praetorians did wear their distinctive clothing, especially the civilian toga. And while the formal toga may seem like a counter-intuitive military dress to be worn when protecting high-value targets like imperial palaces, the idea behind donning civilian clothing emerged from its inconspicuous nature.

To that end, by the decree of Augustus, the Praetorians couldn’t offend and alienate the ordinary inhabitants of Rome with their intricate armor. Hence they endorsed the use of formal toga, which didn’t make them stand out from the throng, and at the same time symbolized their Roman citizenship. It should also be noted that the Praetorian Guard occasionally flaunted their special standards with attached imperial portraits (imagines).

The Misconception Of The Attic Helmet

The popular image of an ancient Roman military officer is often accompanied by presentations of the stylized Attic helmet. Unfortunately, both archaeological pieces of evidence (or lack thereof) and private relief works tend to dismiss the practicality of such Attic helmets.

This certainly alludes to the hypothesis that the Attic helmet depiction was mostly used as an artistic nod to Greek heritage in Roman circles (when it came to commemorative columns). In that regard, both ordinary Roman legionaries and the Praetorians probably wore simpler helmets (like the Montefortino-style) in actual battle scenarios, at least during the early part of the Roman Empire. This, in turn, relegates the possible use of Attic helmets in ceremonial parades.

And as we mentioned in the earlier entry, the same scope mirrored the shields and tunics worn by the Praetorian Guard. Simply put, there was no dedicated shield design or clothing apparel made specifically for the serving Praetorians.

Like their regular legionary brethren, the guards made use of both the renowned scutum and the oval shield, with the latter possibly being more ‘fashionable’ for the Praetorians during the late period of the Roman Empire.

The Battle-Ready Praetorians

Till now, we have talked about the political aspirations of the Praetorian Guard. However, there is no denying the fighting capability of these elite guards, especially in the nearly two centuries before the incident of the infamous auction (in 193 AD). To that end, we fleetingly mentioned how the Praetorians took part in some battles aimed at curbing the mutinies of the Pannonian legions in Germany, after Augustus’ death.

The frequency of their military encounters rather increased in the latter part of the 1st century AD, when Roman emperors actively took part in campaigns. And in many ways, the apical stage of their battle-hardiness came to the fore in the 2nd century AD, with the guards showcasing their aptitude and courage as frontline troops in both the East and the North – so much so that their victories are celebrated by the column of Marcus Aurelius.

The Infamous Auction

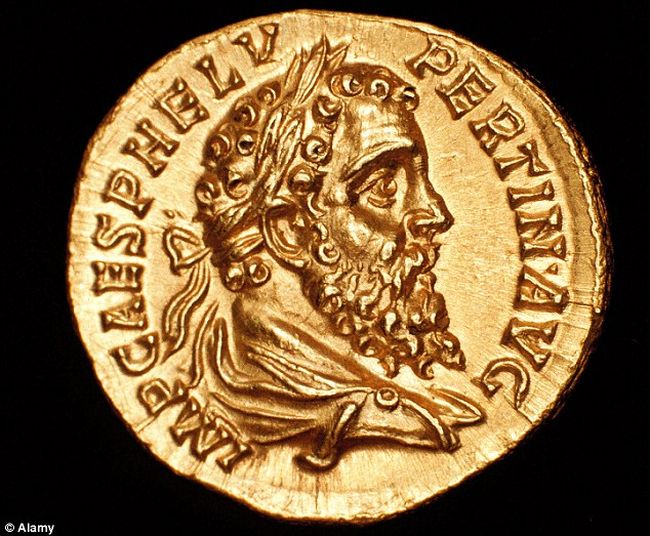

After the assassination of Emperor Commodus (son of Marcus Aurelius) fueled by a conspiracy led by his Praetorian Prefect Lactus, the throne was presented to Pertinax, who played his role in the murder. Now Pertinax, born the son of a freed slave, progressed his career from being a teacher to holding important political posts, including that of a provincial governor and an Urban Prefect.

And while the new Emperor, on his ascension, paid bonuses of 3,000 denarii to each of the Praetorians, many of the guards were presumably not happy with the donation figure. But the last straw equated to a planned reform by Pertinax that would have imposed stricter military discipline on the ‘pampered’ Praetorians.

According to Cassius Dio’s Historia Augusta, around two hundred guards rushed through the gates of the palace to finally murder the Emperor. This led to one of the most infamous episodes in the imperial history of Rome. In many ways, the Praetorian Guard put up the empire for auction – according to Dio’s account, which may have been exaggerated on some levels.

In any case, Dio mentions how the guards conducted their bidding wars for the vacant throne atop the walls of Castra Praetoria. The imperial throne itself was finally ‘purchased’ by one senator named Didius Julianus. But unfortunately for Julianus, the Danubian legionaries had already chosen Septimus Severus as their Emperor, who successfully laid siege to Rome itself during the notorious event. On gaining access to the ‘eternal city’, Severus promptly disbanded many of the Praetorians and replaced them with his loyal soldiers.

The Fall Of The Praetorian Guard

One of the significant political events of the Roman Tetrarchy in the early 4th century AD pitted the two Emperors Constantine and Maxentius against each other. The retreating armies of the latter finally took refuge in the well-fortified city of Rome itself, when the armies of Constantine invaded Italy in 312 AD.

And while Maxentius presumably didn’t have the support of the masses, he was backed by the Praetorian Guard who indulged in many of the state-sponsored massacres. In any case, Maxentius resolved to meet his rival’s army north of Tiber by the approach to Rome.

Then followed a debatable decision to build a pontoon bridge parallel to the stone-made Milvian Bridge. Now according to some, this new access point was constructed because the pre-existing Milvian Bridge was either damaged or too narrow for a large army to pass. Other ancient sources mention how the pontoon bridge was built as a ‘sinkable’ trap for the approaching army of Constantine.

In any case, it was the Praetorian Guards along with their Emperor Maxentius who had to retreat to this bridge (made of boats) after their formations broke from the devastating enemy cavalry charges. And almost alluding to a poetic end to their politically corrupt legacy, the pontoon bridge collapsed under the weight of the soldiers, thus causing many of the guards to drown along with Maxentius himself.

Shortly afterward, both the (remnants of) Praetorian Guard and the Imperial Horse Guard (discussed in the last entry) were unceremoniously dissolved under the decree of Constantine.

Honorable Mention – The ‘Other’ Elite Guards

Given the vast and varied scope of the ancient Roman military forces, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that the Emperors fostered the creation of elite units other than just the Praetorian Guard. One of the primary examples from the beginning of the Roman Empire (and even the end of the Roman Republic) would pertain to the Germani Corporis Custodes. As the name suggests, these men were drawn from Germania, especially from the Batavian and Ubii tribes residing in Lower Rhine.

Other similar troops were possibly also recruited from Gaul. Now as for their organization, instead of being inducted into the main Roman army, the Germani Corporis Custodes acted as a private paramilitary force of sorts, who were directly loyal to the Emperor and his close generals (without much political affiliation) – thus mirroring the Varangian Guards of the later Eastern Roman Empire.

And while they did have their own military command structure with appropriate officers, induction into the elite unit automatically didn’t guarantee Roman citizenship. Quite incredibly, they were employed as infantry during their guarding duties (alongside the Praetorians), but they mostly took the role of heavy cavalrymen in battle scenarios.

And it has been suggested that the Roman preference for German guards was possibly influenced by their imposing stature and gnarly beards that could have potential assassins anxious.

Early 2nd century AD also brought forth another elite unit in the form of the Equites Singulares Augusti (Imperial Horse Guard), possibly founded by Emperor Trajan (from his German troops) – in a bid to intimidate the Praetorians themselves.

These cavalrymen were specially selected from the auxiliary forces of the provinces, and their recruitment also replicated the singulares bodyguard units of provincial governors. As for their organization and equipment, the Equites Singulares Augusti were divided into the conventional Roman cavalry units (ala) which were armored in a similar fashion as their regular counterparts.

Article Sources: Spectator / Britannica / UNRV / WarfareHistoryNetwork

Book References: The Praetorian Guard (By Boris Rankov) / The Praetorian Guard: A History of Rome’s Elite Special Forces (By Sandra Bingham)

Be the first to comment on "The Roman Praetorian Guard: From Elite Units to Kingmakers"