Introduction

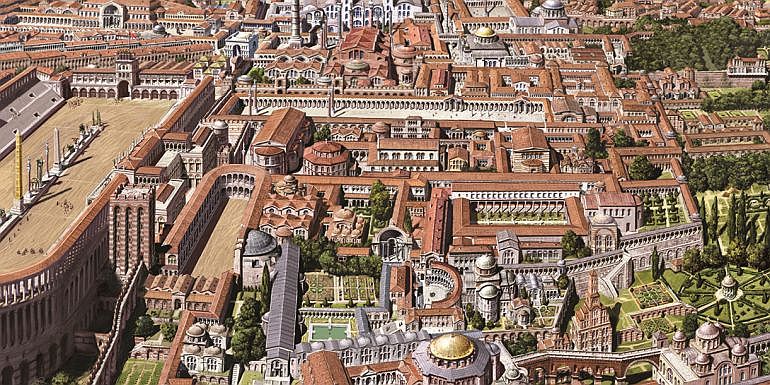

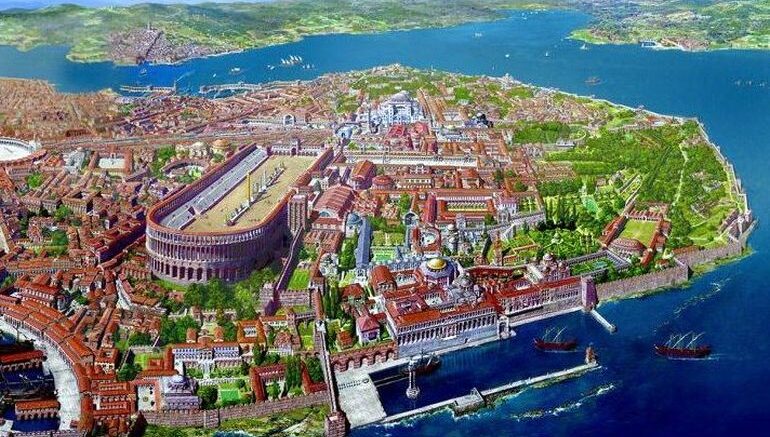

Historically, Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest city in Europe from the 5th to early 13th century AD. To that end, it was Emperor Constantine who truly elevated the architectural ambit of the original settlement, by ‘re-founding’ it as Nova Roma (New Rome or Νέα Ῥώμη). This symbolic overture mirrored the entire shifting of the capital from original Rome to Byzantium in 330 AD, which was then called Konstantinoupolis (or the city of Constantine).

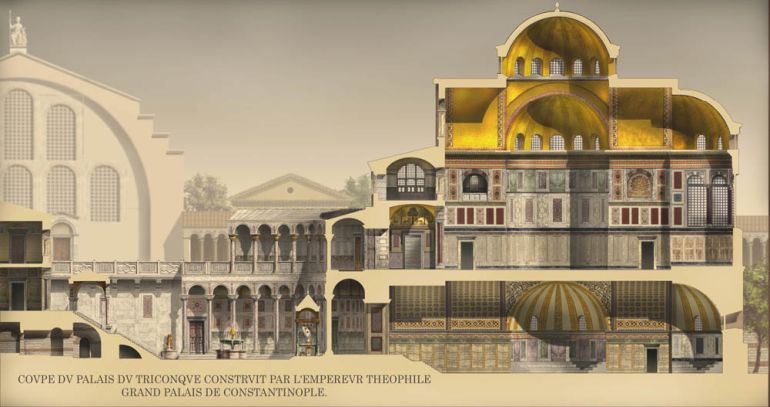

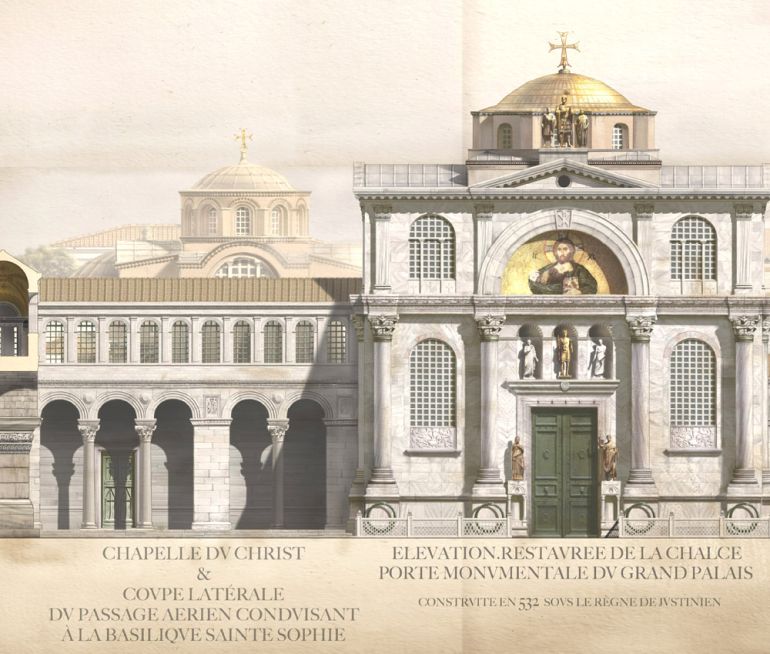

In fact, the massive defense systems of the major Roman city were equally matched by its impressive architectural masterpieces, ranging from the magnificent Greek Orthodox cathedral of Hagia Sophia, the humongous Hippodrome of Constantinople (which was capable of possibly holding 100,000 spectators) to the Great Palace of Constantinople (or Palatium Magnum or Μέγα Παλάτιον) and the triumphal Golden Gate of the complex Land Walls.

In reference to the flurry of these architectural and engineering credentials, Constantinople in itself was also called Roma Constantinopolitana, sometimes accompanied by prestigious titles such as Basileuousa (Queen of Cities) and Megalopolis (the Great City).

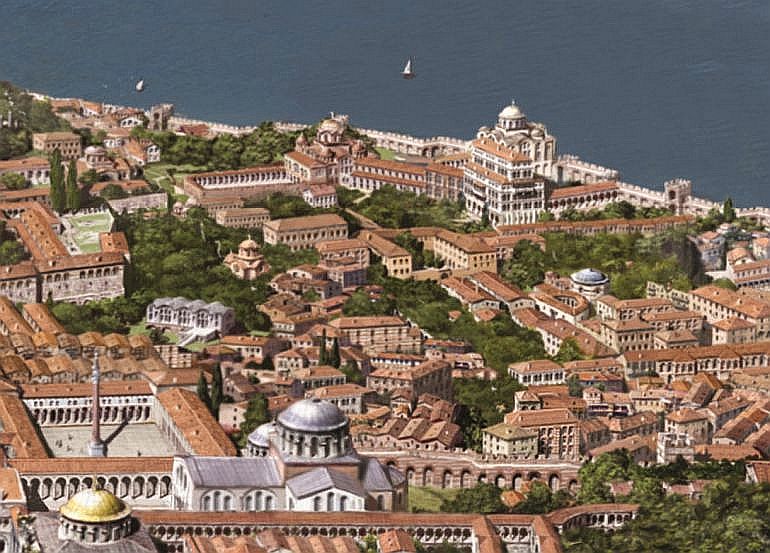

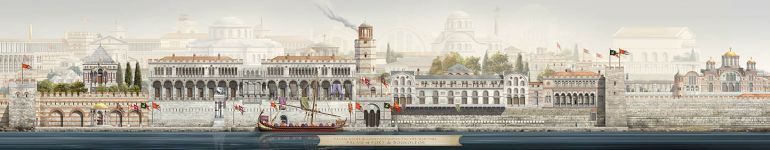

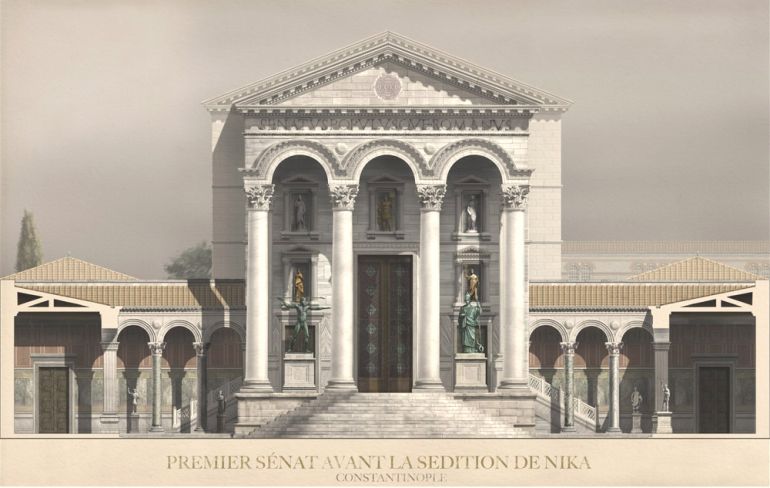

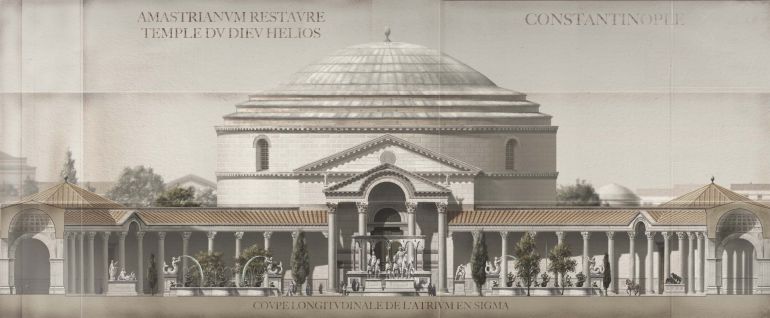

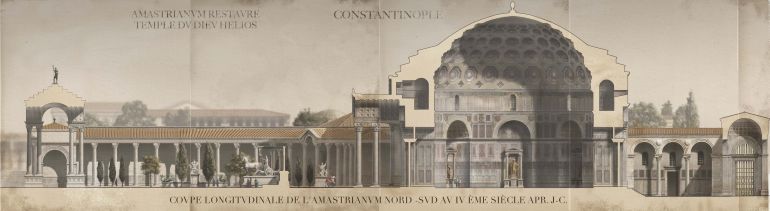

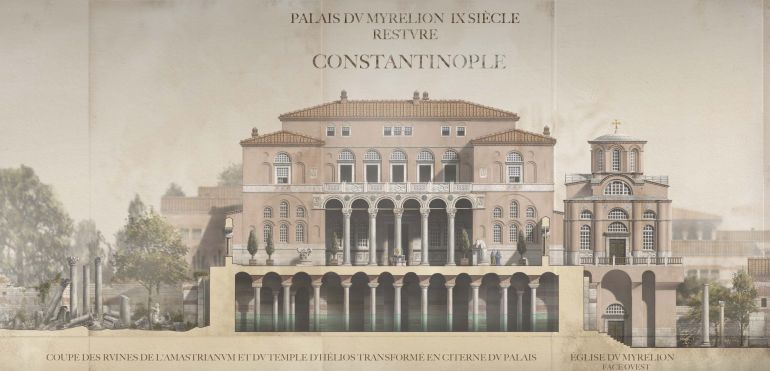

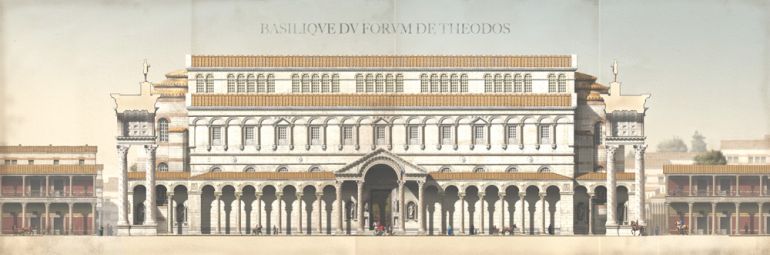

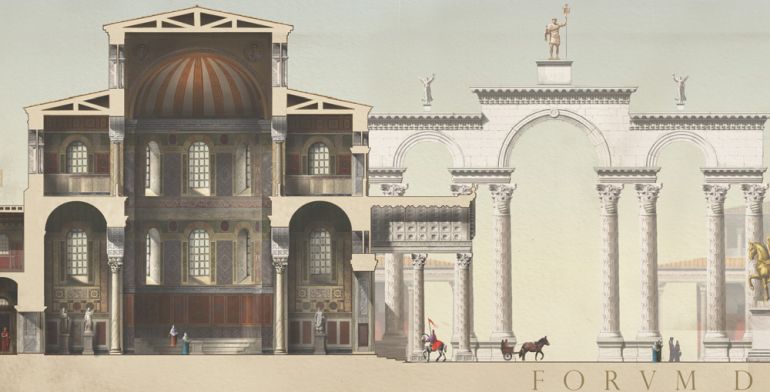

Inspired by the wealth of complex spatial elements, artist extraordinaire Antoine Helbert painted an entire collection of illustrations that portray the historical scope of the last great Roman city in its hey-days from the 4th to 13th century AD. His works, in his own words, cover the numerous plans, elevations, and sections of the major monuments of Constantinople that date from that extensive time frame of 800 years.

Contents

- Introduction

- Reconstruction (Overview) of Constantinople

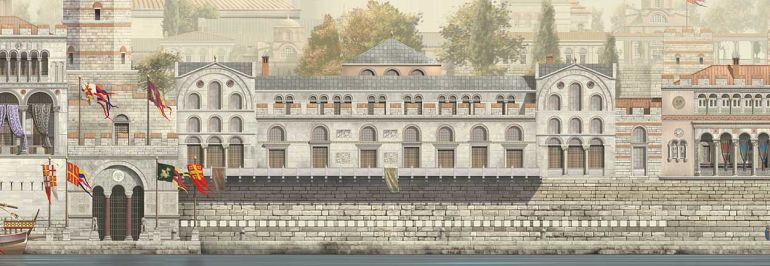

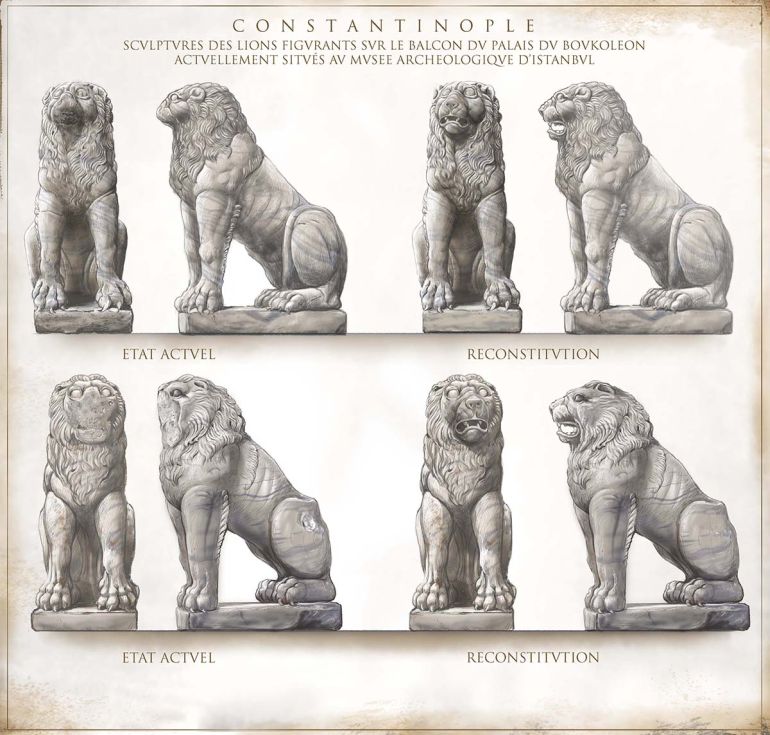

- Elevations and Sections of the Boukoleon Palace (on the shore of the Sea of Marmara)

- Sections of Hagia Sophia

- Other Elevations of Impressive Spatial Elements, from Palaces, Forums to Gates

- The Columns of Constantinople

- Architectural Triumphs of Constantinople

Reconstruction (Overview) of Constantinople

Elevations and Sections of the Boukoleon Palace (on the shore of the Sea of Marmara)

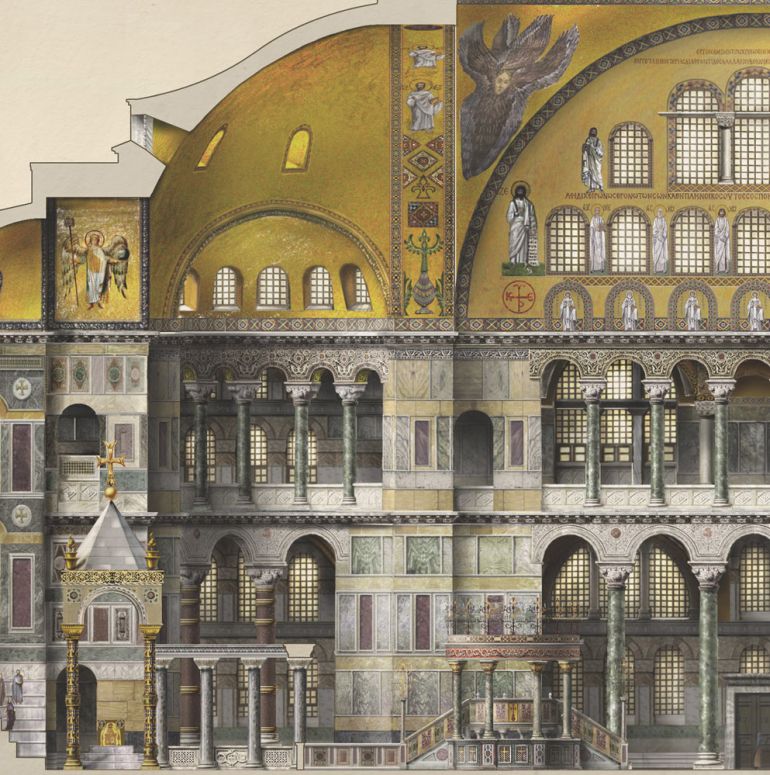

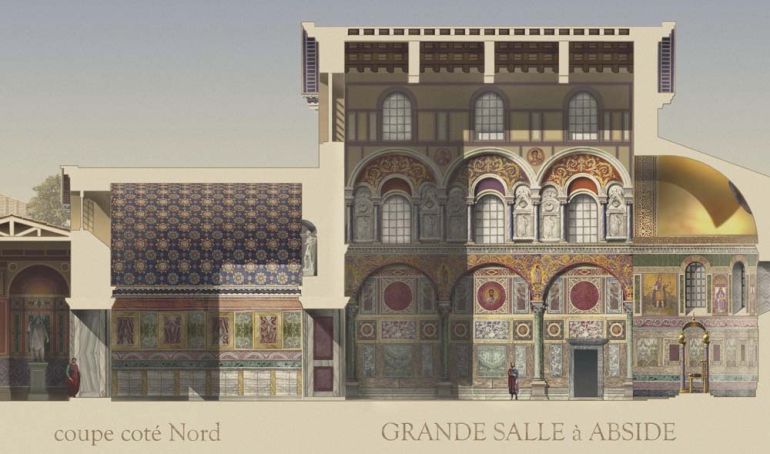

Sections of Hagia Sophia

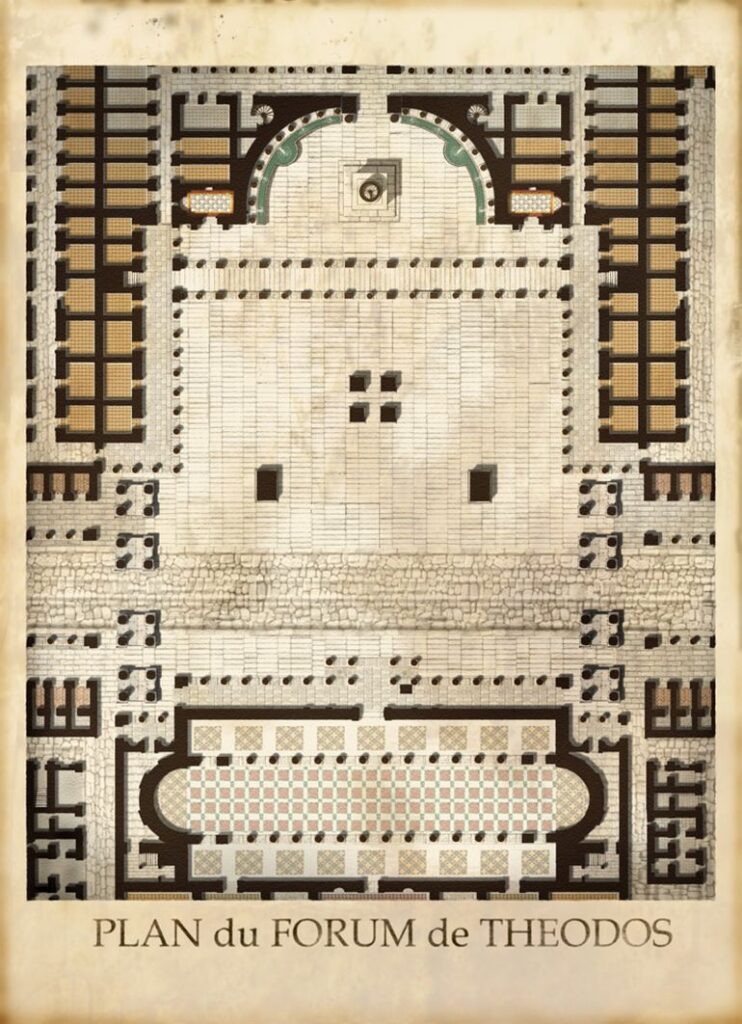

Other Elevations of Impressive Spatial Elements, from Palaces, Forums to Gates

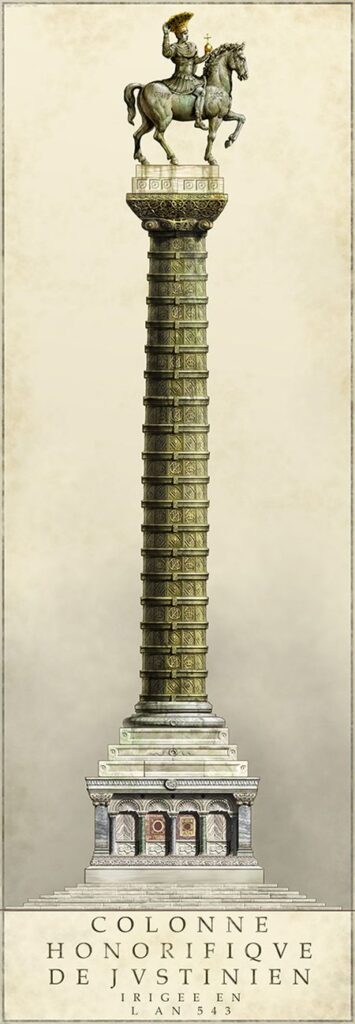

The Columns of Constantinople

And finally, in case you want to take a gander at the images from a singular perspective, you can view the collection in a video format (compiled by YouTuber Quidam Graecus) –

Architectural Triumphs of Constantinople

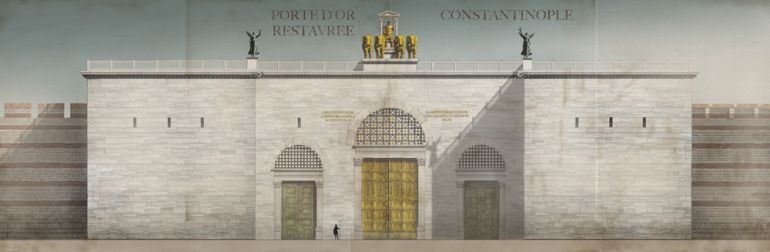

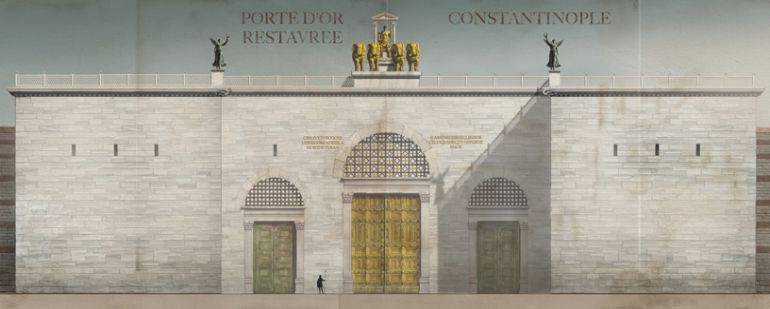

Porta Aurea (Golden Gate)

The Porta Aurea (or Golden Gate), in many ways, symbolically mirrored the rise of Roman Constantinople, with the structure starting out as a triumphal arch (established by Emperor Theodosius) to mark the urbanization of the city.

It has been hypothesized that the arch was constructed to commemorate the victory over the Visigoths in 386 AD, thus suggesting how the structure was emblematically integral to the political fabric of the entire Roman realm after their disastrous defeat at the Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD. In any case, the core arch was then connected and reinforced by one of the most effective defensive systems of the ancient and medieval world – the massive Theodosian Walls.

The triumphal section in itself was partially encased in gilded bronze segments, complemented by vibrantly colored statues. Simply put, this part of the great city was aptly suited to ceremonial processions – as proven by Emperor Heraclius in 628 AD.

He made his triumphal entry into Constantinople through the Porta Aurea in a chariot drawn by four elephants, after defeating the mighty Sassanids and retrieving the True Cross. The impressive gate was later incorporated into a fort with five towers (circa 10th century AD), which in turn was refurbished into the Heptapyrgion, ‘the seven-towered bulwark’ in the 14th century AD.

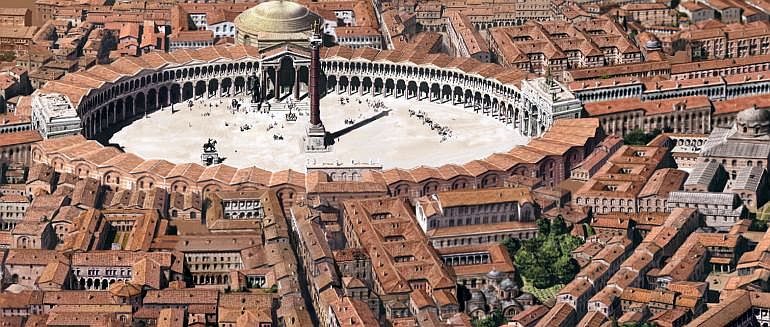

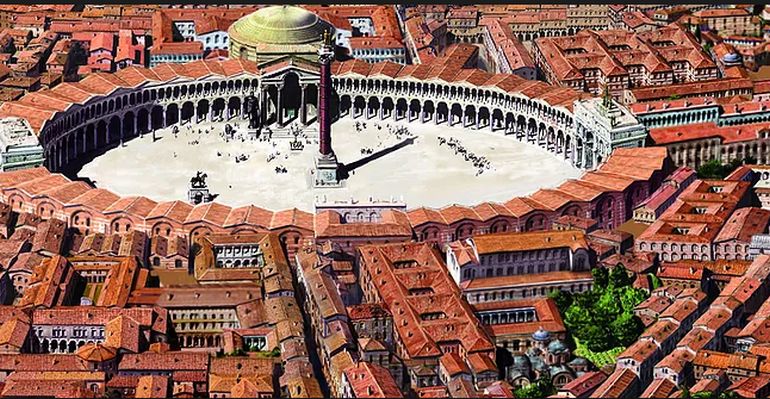

Forum of Constantine

Much like the aforementioned Porta Aurea, the Forum of Constantine was one of the symbolic bastions of the imperial Roman rule in the city of Constantinople. The circular space, originally constructed outside the city walls of old Byzantium, was aptly positioned on the triumphal procession that started from the Golden Gate to the Great Palace.

In terms of sheer size, it is estimated that the Forum of Constantine had a diameter of (140 m) 460 ft, which translates to an impressive area of 167,000 sq ft (the equivalent of almost three American football fields).

This spatial scope had the focal point of the porphyry Column of Constantine at the center, which was crowned by a large statue of the Emperor himself. And the outer symmetry and access to the circular forum were provided by the surrounding two stories of colonnades and two arches of Proconnesian marble, both of which led to the main thoroughfare of the city.

As for a plethora of other architectural and decorative features (including the Nymphaeum), the Byzantine Legacy makes it clear –

On the northern side of the forum, it had a porch of porphyry columns. We are told that the Senate had huge bronze doors depicting the gods and giants at war (which might have been brought from the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus). It is possible that it housed a gilded statue of Constantine that was central to the city’s anniversary ceremonies celebrated on the 11th of May. On the opposite side of the forum was the nymphaeum, a monumental fountain decorated with a series of statues. Both the Senate House and the Nymphaeum were severely damaged by fire around 464.

The forum was also decorated with a large number of statues. The statue that captured the most attention and is most reliably attested was a colossal bronze Athena standing outside the Senate House. It has been suggested that this statue was the Athena Promachos or Parthenos from the Athenian Acropolis. Several sources also say that Constantine brought the Palladium to Constantinople and placed it under the Column of Constantine.

The Palladium was a protective statue that supposedly was first in Troy and later moved to Rome. This was not the only emphasis on Troy; there was also a statue group depicting the Judgment of Paris where the prince of Troy Paris judged which goddess was the most beautiful. There were many other statues, including two bronze female statues on the forum’s western arch which were popularly identified as “the Hungarian” and “the Roman” in the 12th century.

Hippodrome of Constantinople

The construction of the famed Hippodrome of Constantinople was originally started under the orders of Emperor Septimius Severus (probably circa 203 AD). But it took its gargantuan form after the expansion project by Constantine the Great, which translated to a width of 130 m (426 ft) and length of 450 m (1,476 ft). Simply put, the stadium had an approximate area of 629,000 sq ft (the equivalent of more than eleven American football fields) and a seating capacity of over 50,000 spectators.

Much akin to its structural ‘cousin’ in Rome, the Hippodrome of Constantinople was mainly used for wildly popular chariot racing events. The surge in popularity of such sports could be attested by the fervent fans of two rival stables, the ‘Blues’ (Veneti) and the ‘Greens’ (Prasinoi) – many of whom led the disastrous Nika riots of 532 AD that possibly accounted for around 30,000 deaths.

In any case, reverting to the structure in itself, its central longitudinal barrier (known as the spina) boasted a range of columns, statues, and pedestals, two of which were actually dedicated to Porphyrius, the most famous Roman charioteer in the 5th and 6th centuries AD.

Aqueduct of Valens

Constructed in the late 4th century AD (between circa 368-375 AD), by Emperor Valens who was killed in action only three years later in the Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD, the Aqueduct of Valens was possibly an extension of an old Byzantium infrastructure already laid down by Hadrian in 2nd century AD.

In any case, without a doubt, the massive structure, with its arched bridge expanding over a length of 3,186 ft (and height of 95 ft), was one of the major water supply systems of both ancient and medieval Constantinople. In fact, the aqueduct still flaunts its presence in Istanbul as one of the veritable landmarks of the modern city.

Suffice it to say, given its scale and eminent presence, the Aqueduct of Valens was used for providing water to significant areas of Constantinople, including the Nymphaeum (in the Forum of Constantine, which we will talk about in the next entry), the Baths of Zeuxippus and the Great Palace of Constantinople. The structure was later renovated and connected to the gargantuan Basilica Cistern by Emperor Justinian, which had the volumetric capacity for holding 2.8 million cu ft of water (or 21 million gallons of water).

Hagia Sophia

Beyond symbolism, Hagia Sophia proudly stood as the cultural bastion of the Eastern Roman Empire, propelled by its Greek Orthodox faith. Now from the historical context, Hagia Sophia (or ‘Holy Wisdom’) was constructed as a church between 532 and 537 AD, with its patron being none other than Justinian I (also known as Saint Justinian the Great), the Eastern Roman Emperor who briefly restored the borders of the Roman realm along its western sections.

However in 1453 AD, Constantinople was finally conquered by the Ottoman Turks, and the basilica was promptly converted into a mosque. And it was only in 1935, after a wave of secularization, that Hagia Sophia was turned into a museum – though there have been recent calls by some Turkish nationalists to revert it to a mosque.

As for the architectural scope, Hagia Sophia boasts an astronomical 12 million cu ft of volume, with an expansive floor area of 65,000 sq ft, which is more than an American football field. To that end, the medieval basilica held the record for the world’s largest cathedral for nearly a thousand years, until overtaken by Seville Cathedral in 1520 AD.

Interestingly enough, mirroring the structure’s changing religious significance over the course of 1,500 years, the architecture was also altered by the Turks, with the addition of minarets and even structural supports that would have protected the building from earthquakes.

Blachernae Palace

The Blachernae Palace is named so because of its location in the northwest corner of Constantinople comprising the suburb of Blachernae. During the peak period in the city’s history from the 4th to 11th century AD, this structure, though boasting its fair share of grandeur, was sort of a secondary residence for the imperial family, with most rulers tending to favor the Great Palace on the eastern side.

However, the ascension of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (in the late 11th century) marked a pivotal period for the Blachernae Palace, with the ruler shifting the main imperial residence to the particular compound. The Soros Chapel (as showcased in the animated video) was a part of this impressive palace complex.

In the 12th century AD, Manuel I Komnenos ordered the construction of a wall system specifically fortifying the Blachernae district, which was later probably strengthened and even extended to connect to the Theodosian Walls. In spite of such measures, the Walls of Blachernae were possibly the weakest link in the land defenses of Constantinople – and it was through this point that the Crusaders managed to gain access into the fortified city during the infamous episode of 1204 AD.

Pantokrator Monastery

The Monastery of the Pantocrator (later converted into the Zeyrek Mosque by the Ottomans), constructed circa 1124 AD, was dedicated to the Christ Pantokrator (‘Christ Almighty’). The structure, originally comprising the main church along with a library and a hospital, was constructed by the monetary efforts of Byzantine Empress Eirene Komnena.

Later on, Emperor John II Komnenos expanded the complex by adding another church, along with a courtyard, an entrance zone (exonarthex), and two shrines that connected to a chapel dedicated to Saint Michael.

This latter structure became the imperial mausoleum of the rulers of the Komnenos and Palaiologos dynasties. And interestingly enough, during the Latin interlude, the massive complex of the Pantokrator Monastery was used as the see of the Venetian clergy.

It was also repurposed into a makeshift palace by Baldwin, the last Latin Emperor. However, the monastery was once again reverted to its original usage pattern by Orthodox monks, after the Palaiologan restoration of Constantinople in 1261 AD. And the Unkapani cistern that ran underneath the complex was possibly supplied by an alternate water line, as opposed to the famed Aqueduct of Valens.

*The article was updated on 10th March 2020.

Images Source: Portfolio from Antoine Helbert

Be the first to comment on "Reconstruction of Constantinople: From 4th to 13th Century AD"